The Turkic epic tradition has its roots in Central Asia. Many of the prominent oral epics of the Turkic groups (some of which, like Kisekbash and Büz Eget, were turned into books in the 18th–19th centuries) are part of the cultural heritage of these peoples, for they serve as the principal repository of their collective memory. Nomadic societies passed down their history as well as their complex mythological worldview through oral epics and other folk genres.1

The history of the Turkic literature dates back to as early as the 6th and 8th centuries, the period that also marks the existence of the Turkic Khaganate. It was at this time that “ancient Turkic literature” as we know it now developed its distinct stylistic verses and genres that became the cornerstones of the literary tradition (also see Stebleva, 2007). Earlier oral traditions influenced the subsequent written literary tradition, and the elements of folk and written text forms continue to influence each other to this day.

The first works of ancient Turkic literature, runic inscriptions, appeared in the Eastern Khaganate.2 These runic inscriptions contain descriptions (such as those of khagans and battles, military expeditions), epithets (such as blue sky or kök tangri, brown earth or jagzy jip, red blood or qyzyl qan), as well as proverbs and sayings (didactic maxims). Researchers suggest that distinct stylistic verses and phrases found in the inscriptions, such as those in honor of Kül-tegin and Bilge-kagan, are also found in oral fables and legends formed around epic heroes.

The close connection between inscriptions and oral epics is also evident in the literary verse that indicate transitions from one episode to the next (like in the inscription in honor of Tonyukuk) – “After I heard those words…,” “Having heard those words, I moved the army…” Authors of inscriptions appear to appeal to an audience, which according to researchers corroborates assumptions that oral traditions already existed at the time. For example, an inscription in honor of Kül-tegin states – “Listen to my speech till the end.” Such rhetorical appeals to the audience are common in Turkic literature, but are also mainstays of most folk ballads and oral epics of the Balkans, Hungary, England and Spain (Başgöz, 1998, p. 146). We can find similar modes of speech in Kazakh epics such as “Kozy-Korpesh and Bayan-Suluu” and “Kyz-Zhibek,” which emerged later in the 16th and 18th centuries. For example, “They avenged Tolegen. Like a sacrificial lamb, they slaughtered him [Bekezhan]. We will end it here. Now listen to the story about Sansyzbay…” (Kyz-Zhibek, 2003, p. 287). Such turns are common even in the later Turkic folk genres, like the Turkish urban novels of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Book of Korkyt

Grave (mausoleum) of Korkut Ata. Photo by A. Divaev (1898) (see: Zhirmunsky V, Oguzskii geroickeskii epos i kniga Korkuta/Kniga moego deda Korkuta. Oguzskii geroicheskii epos, Moscow-Leningrad., 1962, p. 170).

The Book of Korkyt Ata3 is a prominent example of early Turkic literature that originated as an oral epic transferred over the generations before being written down and published in book form. It is one of the most important sources of knowledge about the social and cultural life of Oghuz as well as the Turkic tribes broadly. It serves as a history of Turkic languages, with their distinct figurative system and foundational concepts of the Turkic worldview, that were gradually transformed under the influence of Oghuz tribes adopting Islam and resettling to Asia Minor (see Anikeeva, 2018).

Oghuz as a confederation of Turkic tribes dwelled in the lower reaches of Syr Darya river and on the coast of the Aral Sea at the end of the 8th century, originally coming from the Southern Siberia and migrating further West to the Caspian Sea. As many medieval Arab historians emphasized, the Oghuz were not monolithic in composition and language. Nomadic Oghuz tribes intermingled with other Turkic and Persian peoples. In the West, they waged wars with the Khazars and Volga Bulgars. In the 10th century, the Oghuz gained in power extending their territories in Northern Turkmenistan and South-Western Kazakhstan, which were correspondingly called ghuz steppes (desht-i-guzan in Persian).

A clan within the Oghuz confederation of tribes, which was under the leadership of Seljuk embraced Islam and gained in power in the 11th century. This clan began to advance West through Transcaucasia, Iran and Asia Minor in the first half of the 11th century, subsequently shaping the ethnogenesis of modern Turks and Azeris. Other Oghuz tribes remained settled near the Aral Sea and later served as the ethnic substrate of Turkmen and to some extent Uzbek ethnic groups. Some of the tales that later became part of The Book of Korkyt Ata were developed in the same era. This is evident from the references to the Age of Oghuz in the epic, which dates back to the 9th-10th centuries.

The Book of Korkyt Ata (Dede Korkut) has kept many indirect evidences that shed light on the period when Oghuz tribes lived in Central Asia. For example, one of the songs in the epic, Tales of the Looting of the House of Salor-Kazan, narrates scenes from the wars between the Oghuz and Pecheneg tribes in the lower Syr-Darya in the 9th and 10th centuries. Such scenes were narrated by Abu-l-Gazi in the “Genealogy of Turkmens” (see Zhirmunsky, 1962, p. 181). Korkyt himself, remains as a major hero in Turkic folklore of Central Asia to this day. Numerous Kazakh legends that were recorded by Veiliaminov-Zernov, Chokan Valikhanov, G.N Potanin, A. Divaev, I. Kastan’e and many other scholars, make references to the grave of saint Khorkhut-ata located in the lower Syr Darya (for more information, see Lerkh, 1870, p. vii-xiii; Divaev, 1990). According to these legends, Khorkhut or Korkyt, was a healer (baksy in Kazakh or a shaman) who declined money in return for his treatment and help. People believed that he continued his miraculous work even after his death, and the alleged burial place of Khorkhut-ata turned into a pilgrimage site for those who seek to recover from illness.

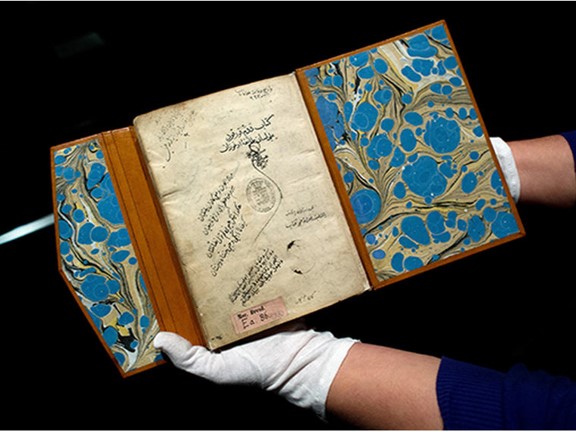

Dresden’s List of the Books of Korkut. Source: University Library Dresden (SLUB)

The Book of Korkyt relies on prose, but also includes different expressions, proverbs, sayings and rhymes, which include the main characters’ invocation to the water, trees and other elements of nature as well as the divinations of Korkyt himself.4 For example, there are proverbs such as these: “Those who have ribs will rise, those who have cartilage will grow” (Song about Sekreka, son of Ushun-Koji, The book of Korkut, p. 90), “One man in the field will not be a knight, the bottom of an empty vessel will not hold tight” (Song about Amran, son of Bekil; The book of Korkyt, p. 87). Expressions where a narrator appeals to his or her audience (see above) are also ubiquitous. For example, “Let’s see my khan, what he said” (Görelüm Hanum ne soyladı). Furthermore, metaphors comparing warrior troops with streams of water or a heavy rainfall are consistently present in the epic. In response to the request of Salor-Kazan to interpret his dream, his brother Kara-Güne replies: “You saw a black cloud – that is your happiness; you saw snow and rain – that is a warrior troop; hair stands for care; blood stands for tragedy; and the rest I cannot interpret, may Allah show you the meaning.” The connection of water and blood consistently appears in various figures of speech including metaphors and hyperboles in the epic. Korkyt’s words conclude each story and include expressions such as these: “Let us be able to cross rivers of blood” (Kanlu kanlu sulardan geit versün); “Your blood ran like water” (Qanyŋ subča Jügürti) (Malov, 1951; Orkun 1987). The epic Oğuzname that also includes similar expressions: “Fights and battles were so cruel that the waters of the Itil River turned red” (Scherbak, 1959).

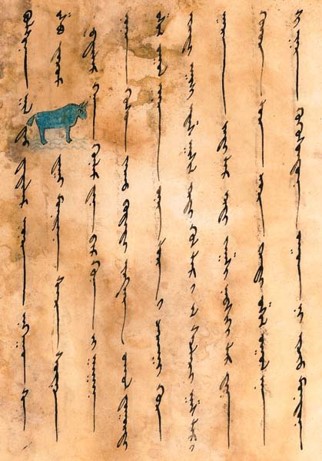

“Oguz-name”, Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (MS Supplément turc 1001)

Although the Book of Korkyt Ata originated in the pre-Islamic period, Turkic groups embraced Islam and subsequently drew from the Islamic literary tradition as they further reproduced the epic. For example, consider this metaphor of life as a caravan: “My grandfather Korkyt composed a song and shared this tale. He said – they came into this world and passed; so the caravan arrives and takes off; they were abducted by death and hidden by the earth; who did the perishable world remain to?” While expressions like this may draw from various sources, they primarily borrow from hadiths and the broader Islamic written literary tradition. The same metaphor of life as a caravan is also found in Abu-l-Ghazi’s chronicle “The Genealogy of Turkmen”: “Children of Adam are like a caravan, some wander, and others stay in the barn” (The Genealogy of Turkmen 332-334, see in Kononov, 1958, p. 45). Comparisons of earthly life and its ephemeral nature to the eternity are not new for the Turkic literary tradition – it appears in various didactic compositions from the time Turks adopted Islam. For example, formulations similar to those from Kitab-i-dedem Korkut are also found in the essay by a Central Asian poet and thinker Ahmed Yugneki, “The Gift of Truths” dating back to the 12th century.

The Epic of Edigey

The epic of Edigey (or Edigeh) is another notable literary work in the common heritage of many Turkic peoples. Different versions of the epic are recited and retold among many Turkic groups from the Caucuses to Siberia and from Crimea to Altay. Allegedly, Edigey was a commander-in-chief of the Golden Horde armies.5 P.A. Falev rightly notes that the events that form the historical basis of the epic Edigey and its interrelated legends about Chora-batyr took place in the 15th and 16th centuries in the Nogai Horde. At the core of the epic is a story about the hero Edigey6 and his associates, descendants (the Horde princes Nuradin/Nuradil, Musa Khan, Urak and Mamai, Ismail, Yamgurchi) and their exploits against various foes. We learn about the feud between Edigey and the Golden Horde Khan Tokhtamysh (Toktamys) and the latter’s close associates Yambai (Djanbai) and his son Kadyr-Berdi.

Edigey became the de facto ruler of the Golden Horde after Tokhtamysh was exiled, and he ruled for a long time until the sons of Tokhtamysh forced him to flee in 1412 to his Nogai ulus. One of the sons of Tokhtamysh killed Edigey eight years later in a battle. The scholar of the epic V. Zhirmunsky notes that “Edigey’s foreign policy activity known from the Russian chronicles, including the war with Vitovt in 1399 and the campaign against Moscow (1408-1409) did not find a place in the epic.”

Although the epic of Edigey is primarily attributed to the Nogai literature, many different Turkic folktales including those of Kazakhs, Karakalpaks, Uzbeks, Turkmens, Bashkirs as well as tales of Siberian Tatars and Teleuts include stories about Edigey. Researchers take this as another evidence that the legend about Edigey came to life in the Nogai Horde – “the wide geographical distribution of the legend…from the Crimea and the Black Sea steppes to Sibera and Kazakhstan corresponds to the historical framework when movements of Nogai nomads took place, particularly after the Nogai ulus came apart in the 16th and 17th centuries” (Zhirmunsky, 1974). The epic of Edigey subsequently gave rise to other epic series such as those dedicated to the descendants of the hero – for example legends about Urak and Mamai or the legend about Chor (Shor)-batyr. The legend of Urak and Mamai narrates about the feud between the descendants of Edigey in the 16th century. Musa Khan’s son Ismail (who allied with Ivan the Terrible) kills his brother Urak (see Trepavlov, 2002). Many other local short fables that exist among various Turkic ethnic groups also narrate stories about characters related to Edigey.7 For example, a Nogai fable about Saint Baba Tuklas, the legendary ancestor of Edigey, documented by Chokan Valikhanov, narrates why Edigey’s descendants are called aksuyak or white bone.

The main part of the epic of Edigey is considered to be historical, transformed by folk and poetic fantasy. Hence the struggle of Tokhtamysh and Edigey in the epic is transposed through the genre of folktales into a story of evil king unjustly pursuing his faithful and noble vassal (a similar motif is common in epics in general, see for example the Spanish Song About Sid, where King Alphonse VI pursues Sid Campeador).

Similarly, Edigey as a real person who gained fame as a highly successful general and leader of the Nogai Horde, is fictionalized in the epic and described as a hero of supernatural strength, ingenuity and wisdom.8 There are many stories that illustrate the wisdom of Edigey. In one, he resolves a dispute between two men who were arguing over a colt. Edigey leads two mother camels to the river and puts the colt in a boat. One of the camels overcomes her fear of water and rushes after the boat that would otherwise have been carried away by a currant. Yet in another story, Edigey resolves a dispute between two mothers over a child (akin to the biblical story about Solomon), and a squabble between four brothers over their inheritance. Finally, it is also said that Edigey avoids getting poisoned by Tokhtamysh, by dividing a poisoned drink into many bowls.

The very birth of Edigey is described as a miracle. This motif of the birth of an epic hero from heavenly spirits or from the Sun is common in Turkic folk genres (also see, Oghuz Khan, “The Genealogy of Turks”). According to some stories, he was born from the union of a “forest spirit” and khan Shakh-Timur’s falconer Kutly-Kaya. In the version recorded by Chokan Valikhanov, Edigey descends from one of the Muslim saints and a maiden – “Edigey descended from Baba Tukhlas; his father was Kutlu-Kaya.” In some versions, the maiden is known to be Kün Sulu, the daughter of the Sun, and yet in other versions, she was the daughter of the spirit Albasty (Valikhanov, 1904).

The title page of the manuscript “The book of my grandfather Korkut” from the Dresden Library.

A few other elements of the epic run in parallel with other epics and legends of the Turkic literature. Edigey’s battle with the warrior Alp (also known as Alyp-Batyr, Khabardin Alyp) as a result of which, he frees the beautiful daughter of Shah-Timur (also known as Sa-Temir) is for example commonly narrated by other epics. Edigey kills Alp with an arrow from his own bow, as the latter takes his seven-day long sleep. The legends of Edigey introduce audiences to another important character – Sabyra-yirau (also known as Supra-Jyrau, Safar-jyrau) who served in Tokhtamysh khan’s court as a bard, khan’s adviser and soothsayer. Grandfather Korkyt in The Book of Korkyt Ata, similarly served in the court of Oghuz Khan Bayindar, and was known as a bard and soothsayer.

The epic of Edigey reached us in different incarnations as various scholars encountered the epic among different ethnic groups, recorded them and put them into a written form. It was G. Spassky who was among the first to collect and study different versions of the legend of Edigey;9 he published a Kazakh version of the legend in the Siberian Herald magazine in 1820. Ten years later, a Polish orientalist Alexander Khodzko published legends of Edigey in English, after recording them based on the version narrated by Astrakhan Nogais (A. Khodzko, Specimens of the Popular Poetry of Persia, 1842). P.M. Melioransky, a professor at St. Petersburg University published “The Legend of Edigey and Tokhtamysh.”10 This edition was based on a Kyrgyz (i.e. Kazakh) version, that had been recorded by Chokan Valikhanov and his father Sultan Chingis in 1841-1842. Valikhanov and his father, in turn, documented the version told by a Kypchak bard poet and two Kazakh poets. The Nogai versions were recorded and published by M. Osmanov (1883) and I. Berezin as well as in different translations and interpretations.

The featured image is an architectural monument displaying kobyz (Kazakh music instrument) in honor of Korkyt Ata was erected in 1980 in the Karmakchinsky district of the Kyzylorda region of Kazakhstan. Authors – architect B. Ibraev and acoustic physicist S. Isatayev. When the wind blows, it starts to sound and all passing people can hear the melody of the wind. The monument is also visible from the windows of passing trains passing, following from Moscow to Tashkent and Almaty (source: Wikipedia).

- The Manas epic of the Kyrgyz people and Olonkho of the Yakut people are prominent examples. ↩

- The Turkic Khaganate split into two independent confederations of tribes, the Eastern and Western Turkic Khaganates, by the beginning of the 7th century. ↩

- Also known as Oğuzname or the Legend of Okhuz Khan. ↩

- The epic is a rich ground for formulaic language of the oral tradition. Formulaic language is a linguistic term for expressions or fixed combinations of words that convey commonly shared meanings (formula thought) (Başgöz, 1998, p. 131, 141); these expressions have a particular rhythm, and are concise and easily memorable, like proverbs or sayings. Formulaic phrases are commonly used in literary traditions of the Near and the Middle East (see, for example, the Arabic “Syrat Antara,” [Kudelin, 1978]). ↩

- In his unpublished work about the epic of Edigey, P.A. Falev wrote: “Nogai was a powerful prince in the Golden Horde and ruled over Mangyts. After his death in 1300s, Mangyts came to be called the Nogais. The Nogais had an extremely interesting story, which was all reflected in their epic…” (see Anikeeva, 2018). ↩

- Also known as Edigeh, Idigey or Edyge. ↩

- The Tatar version of the legend about Edigey is related to the original Nogai version, but maintains its independent status as a notable example of Tatar folk tradition. ↩

- Such descriptions are typical in other Turkic epics like those about heroes Seyid Battal-gazi, Sultan Melik Danyshmend and Kör Oglu. ↩

- It must be noted that the legends about Edigey were passed down orally, but also through written manuscripts and through integration into other works. To illustrate, one of the versions of the legend is included in the 17th century essay “Daftar-I Genghis-nameh” written by Utemish-haji Muhammad Dosti. ↩

- Melioransky was first to identify the main characters of the epic and to suggest that the epic was based on historic events. ↩