Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov

“Now I shall go far and far North playing the Great Game…”

RUDYARD KIPLING, KIM, 1901

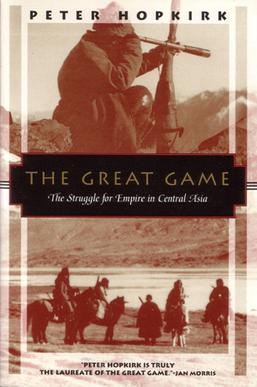

During the summer weekends across the United States as the heat wave is hitting the streets in the cities, whether on a picnic in a park or by the seaside, our readers would certainly enjoy this amazing book written by a very skillful writer and historian Peter Hopkirk. Described by The New York Times Book Review as “the stuff of a dozen adventure movies, everything a ripping yarn should have” and The Washington Post as “told in great style”, this volume will beyond captivate the minds of readers with an array of fascinating stories of a bygone era.

Although the phrase “The Great Game” was first coined in Rudyard Kipling’s famous novel Kim, Peter Hopkirk’s contribution is immense in terms of narrating this story in wonderfully suspenseful prose.

Despite the notion that the “Great Game” phrase refers to the historic period of nineteenth century to depict the competition between Russian and British Empires, Hopkirk begins his book by sharing the story of the Mongol hordes that attacked Russia in the thirteenth century and how this might have affected the aspirations of the great powers. As Walter Laqueur argues, “in the lonely passes and blazing deserts of Central Asia, a deadly struggle took place between the two superpowers – Victorian Britain and Tsarist Russia. One of the most gripping episodes in imperial history, it is known today as the Great Game… Peter Hopkirk’s acclaimed, spellbinding account tells the story of this great imperial struggle for strategic and economic supremacy fought across a cruel and desolate terrain… When play first began, the frontiers of Russia and British India lay some 2000 miles apart. By the end, as the caravan towns of the Old Silk Road fell one by one to the fast riding Cossacks, this had shrunk to less than twenty in place…”.

There has been much of the study on the Great Game and whether this phenomenon continues to live on in our days. Politics aside, we would like our readers to engage in a historical journey of exploring more about the region through these detailed, personal and at times surprising accounts of the Central Asian region so well depicted by the well-known British historian and author.

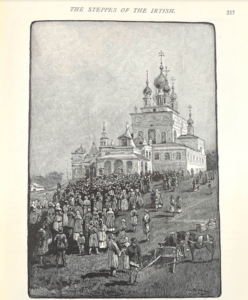

Hopkirk himself describes some of the endeavors undertaken by Victorian Britain and Tsarist Russia as following. In case rumors began to leak out about the preparations, the expedition was to be officially described as a scientific one to the Aral Sea, which lay on its route. Indeed, in the coming years, Hopkirk explains, “scientific expeditions” were frequently to serve as covers for Russian Great Game activities, while the British preferred to send their officers, similarly engaged, on “shooting leave”, thus enabling them to be disowned if necessary1. Hopkirk also shares the accounts that the Tsar was concerned about reports on the outposts of Syr-Darya that British agents were becoming active in the region. If this were to turn into a race of valuable markets of Central Asia, then St. Petersburg was determined to win it2.

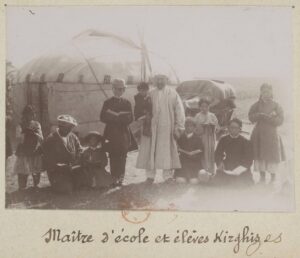

Interestingly, on page 74 of this volume, Hopkirk describes Kazakhs as those who roamed the vast steppe region to the south and east. He then shares the accounts of one British War Office colonel, who said that “10 thousand Kirghiz/Kazakh horsemen might be able to traverse a difficult road… with nothing but what can be carried at the saddle bow”3.

The author also shares the observations made by Indian Army captain named John Macdonald Kinneir who recognized that “supplying an invasion force attempting to cross Central Asia would present a colossal problem. The great hordes, he wrote, which formerly issued from the plains of Tartary to invade kingdoms of the south, generally carried with their flocks the means of their sustenance. Nor were they encumbered with the heavy equipment necessary for modern warfare. They were thus able to perform marches which it would be utterly impossible for European soldiers to achieve”4.

Unlike other volumes of that time, Hopkirk’s accounts do not focus extensively on geographical and topographical portrayals of Kazakh cities but interestingly, the author describes Chimkent and Turkestan as oasis towns5.

These and many other accounts would certainly enrich anyone’s knowledge interested in the study of the Central Asian region and world history overall. We hope that our readers enjoy this volume as much as the rest of the vibrant academic community studying these historic periods in detail.

Readers may acquire “The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia” here.