It is known that dance is a bodily expression of human feelings and emotions. Every nation has its own lexicography and distinguished style of dance. How things were with the development of Kazakh dance?

In this interview, Anvara Sadykova, Senior Teacher at the Kazakh National Academy of Choreography, Astana, and historical dance as well as the history of the world and national choreography, talks about the long history of bold and expressive Kazakh dances, how they mirrored the lives of the steppe nomads, expressed their feelings and even served as a social parody. A separate question that Anvara helps to investigate is the origins of the popular dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ (Black Pacer) which had been revived recently with astonishing popularity.

ANVARA SADYKOVA, Senior Teacher at the Kazakh National Academy of Choreography, situated in Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, teaches a number of core modules on the Kazakh dance, theory and methodology of teaching Kazakh and historical dance as well as the history of the world and national choreography.

In the period from 2009 to 2021, Anvara staged more than 45 choreographic compositions, including two ballets “Turan dala – Kyran dala” (The Kazakh Land’, 2017) and “Zheltorangy turaly anyz” (The Legend about Turanga, 2020).

Anvara is passionate about promoting Kazakh national dance and choreography. She holds master classes and lectures on Kazakh dance and gives seminars on the history of national choreography in Kazakhstan and abroad.

Anvara, please tell us a little bit about your institution – what place does the study and teaching of Kazakh national dance take in the program of the Kazakh National Academy of Choreography in Astana?

First of all, I would like to point out that The Kazakh National Academy of Choreography is the only higher educational institution in Central Asia with a full cycle of multi-level professional choreographic education. It was opened in 2016 at the initiative of the First President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev. The Rector of the Academy is the People’s Artist of Russia, a world-famous ballerina Altynai Abduahimovna Assylmuratova.

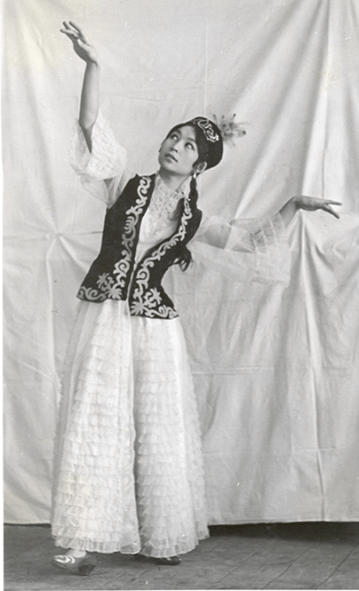

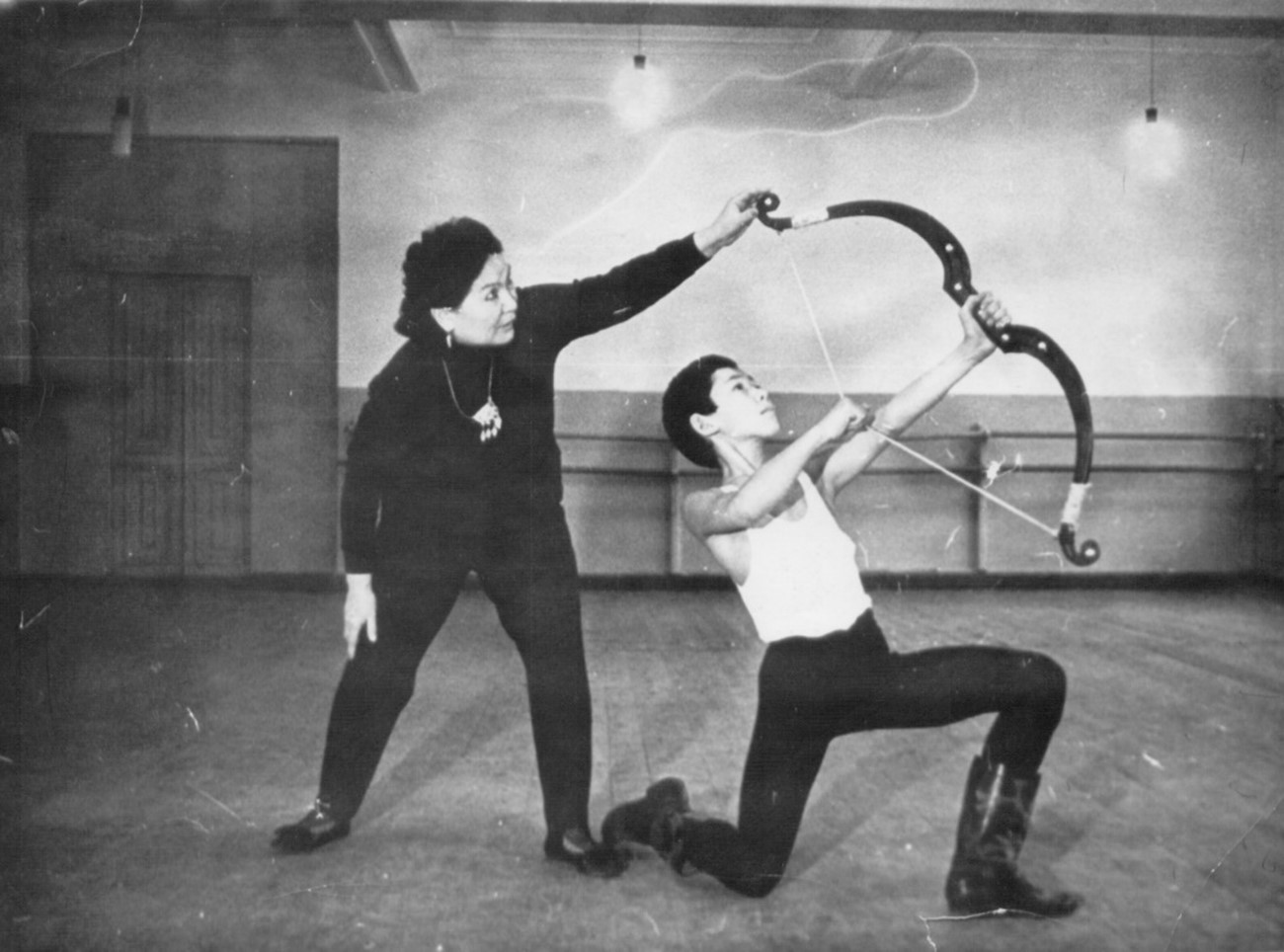

“Kazakh dance” as a discipline was introduced into the curriculum for the first time in 1965 by a professional Kazakh dancer, People’s Artist of Kazakhstan, the legendary Shara Zhienkulova (1912 – 1991). She published a number of books, including the book ‘The Secret of Dance’[1] (1980), where she described Kazakh folk dances in great detail, supplementing it with images of costumes and dance positions as well as musical notes. Shara’s traditions at the Almaty Choreographic College named after A. Seleznev are successfully continued by her former student, an outstanding teacher of Kazakh dance, Gainikamal Beisenova.

At the National Academy of Choreography, the class “Kazakh dance” is included in the professional education program from the 5th year of study and is taught for 3 years. At this level, our students study Kazakh dance as future professional performers, that is, ballet dancers and professional ensemble dancers. Further, undergraduate students study the theory and methodology of teaching Kazakh dance for two years, and then, at the Master’s and Doctoral levels, the students study Kazakh dance from a research perspective. Classical ballet heritage, contemporary choreography and, of course, Kazakh dance make up the repertoire of the Kazakh National Academy of Choreography. I am pleased to say that in January 2021, we introduced the Handbook on Kazakh dance – a collective work carried out by the members of the Laboratory of the Kazakh National Dance: professionals of performing arts, pedagogues, ballet masters, researchers, and other experts working in the field of Kazakh national dance led by Toigan Izim, Aigul Tati, Aigul Kulbekova, Anvara Sadykova and Almat Shamshiev.

There is an opinion that the nomadic peoples did not have their own, historically established folk dance, which was made up for by a rich musical and singing culture. What can you say about this?

This is one of the most frequently asked questions, and it is understandable. However, we dare to disagree with this opinion.

One of the brightest bodily expressions of human emotions by any person or any nation is dance. Nomadic peoples are no exception. Yes, of course, we do not exclude the historical unevenness of the development of the dance culture of our ancestors, but to say that there was no historically established folk dance, I think, is completely wrong!

The longer I work in the field of Kazakh dance, the more I admire the wisdom of our people, the deepest knowledge of our ancestors who were able to leave us a great cultural heritage. Over the centuries, the body language of our folk dance has been formed – expressive, beautiful, giving you the ‘raw’ material to work with, and to stage beautiful choreographic miniatures, compositions, ballets and dance scenes on completely different topics, embracing both the every-day reality and highly philosophical reflections. Such presence of various movements and themes of Kazakh dance could not appear from nowhere, without the fundamental basics!

Unfortunately, the canonical forms of the oldest dances have not reached the present day for various reasons. But the themes of ancient dances and traditional movements are carefully passed down from generation to generation. The works of the researchers and practitioners of Kazakh dance such as Dauren Abirov, Aubakir Ismailov, Shara Zhienkulova, Uzbekali Dzhanibekov, Lidia Sarynova, Olga Vsevolodskaya-Golushkevich developed further by Toigan Izim, Aliya Shankibaeva and Aigul Kulbekova demonstrated evolution of Kazakh dance from ancient times to the present day, as reflected in its spiritual culture.

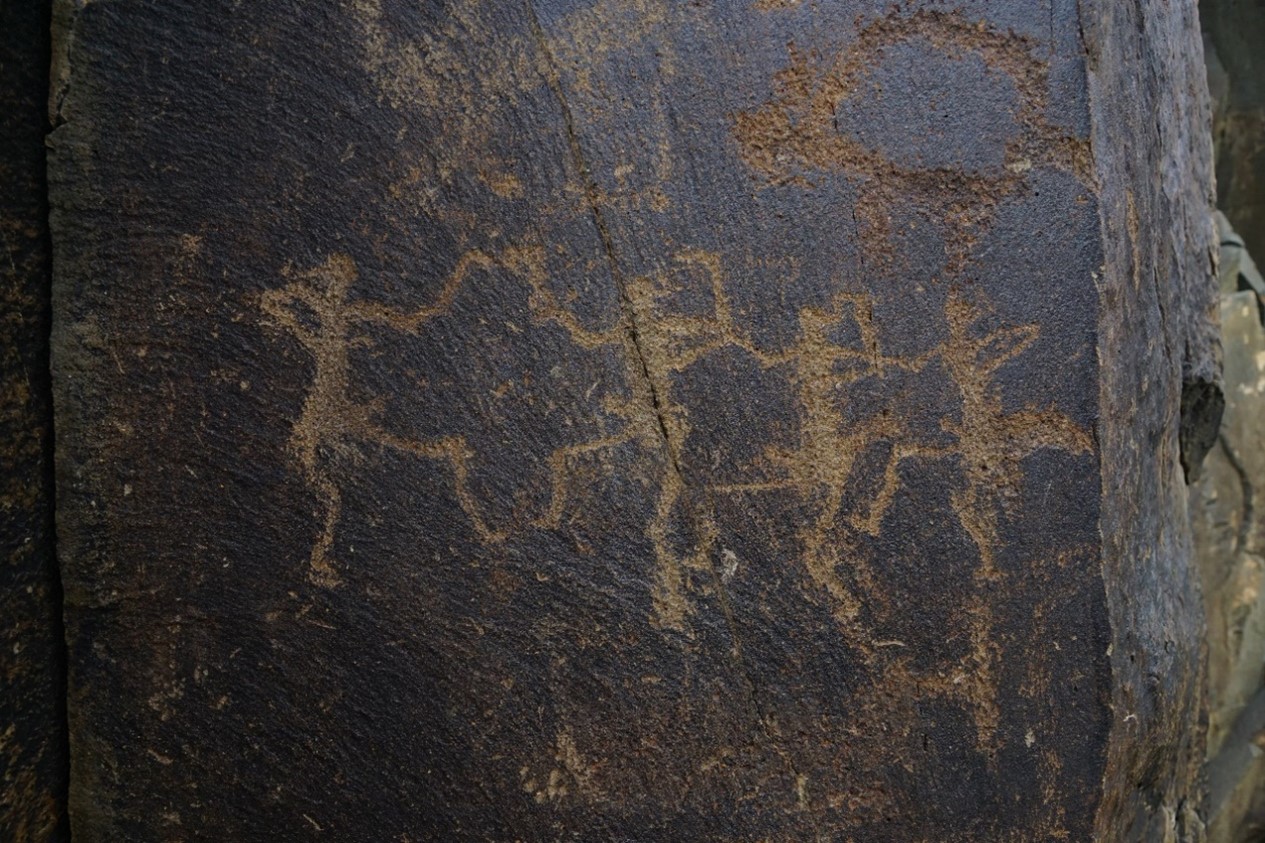

The first documentary evidence of dance is petroglyphs. There is a number of archaeological sites with petroglyphs in the territory of modern Kazakhstan, including the UNESCO-protected Archaeological Landscape of Tamgaly (located 170 km northwest of Almaty) with over 5,000 petroglyphs (rock carvings), ‘dating from the second half of the second millennium BC to the beginning of the 20th century’. Some of the rock carvings captured the whole dance scenes of those ancient times. The majority of photos show clear images of animals; some petroglyphs show people’s figures dancing solo and in a group.

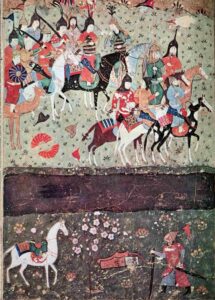

Our ancient ancestors used their flexible bodies as a natural means of expressing their feelings and acted as a means of communication. Their dances had, first of all, a sacred, ritual and ceremonial meaning related to Totem worship, hunting rituals, and rituals of male warriors with weapons preparing for battles. These sacred dances reflected the worldview of our ancestors, their sense and understanding of the surrounding world, natural phenomena, etc. The dance permeated all human life.

The classification of the traditional Kazakh folk dances described by A. K. Kulbekova et al. is an illustration of the origins of the Kazakh dance which reflected the lives, activities, customs and beliefs of our ancestors:

1. Ritual and ceremonial dances; 2. Combative-hunting dances; 3. Work dances; 4. Household-imitative dances; 5. Festive and ceremonial dances; 6. Mass-thematic dances.[2]

A special place in the dance culture is occupied by the dancing art of bakhsy (shamans). Here I would like to recall Olzhas Suleimenov’s poem “Asian bonfires”, which is quoted by the famous choreographer Olga Vsevolodskaya-Golushkevich in a documentary about the activities of the folk-dance ensemble ‘Altynai’. The legendary Kazakh poet highlights the role of shamans (bakhsy) in understanding the world around the Kazakh ancestors: ‘they [shamans] lit the fire and taught how to keep the fire, to bow to the fire, to treat sciatica and chirium with fire, and taught to saddle a horse, and believe the sun, and guess by the stars, from them went – and dance and sing’.

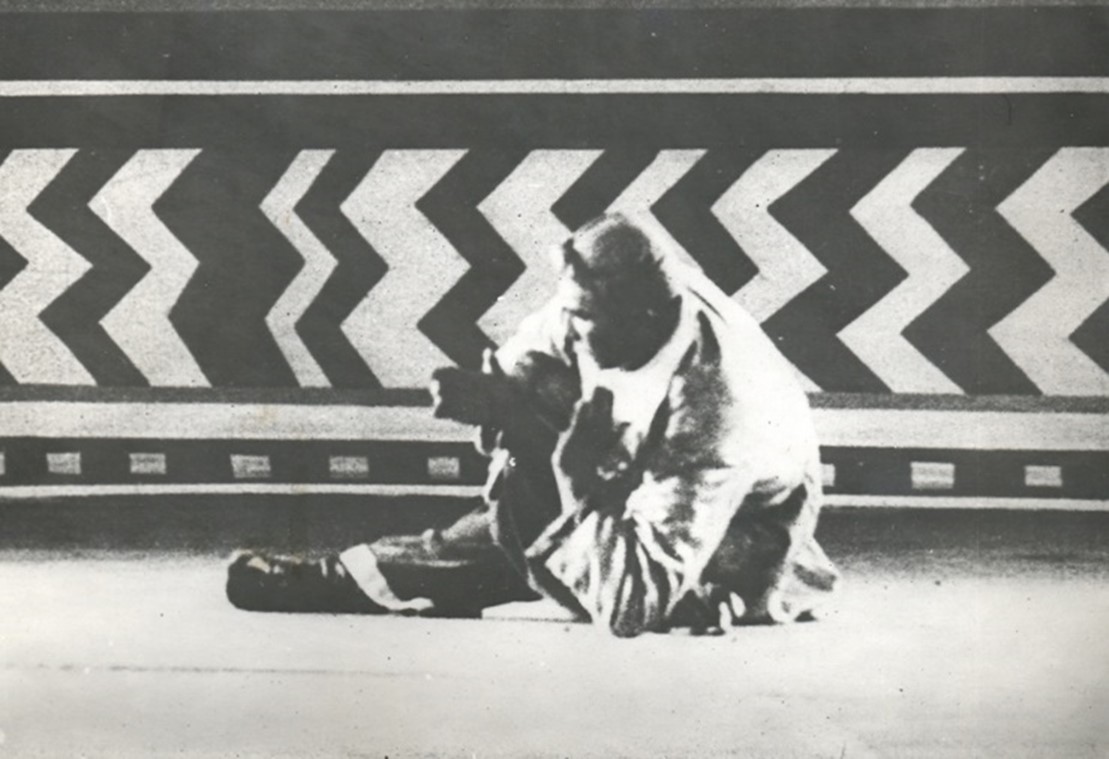

It is known that the main function of Kazakh shamanism was healing. The ritual process took place through a dance action to the accompaniment of percussion instruments, and this was considered the culminating point in the shamanistic ritual, after which the shaman, exhausted, foaming at his mouth, fell unconscious. Musical rhythms and dance moves performed by shamans (bakhsy) were of an improvisational nature. And in general, improvisation would be the main component of the entire national culture in general and would be of great importance for the dance art of Kazakh people, in particular. In the plastic arts of shamans, dance acquired a magical symbolic meaning.

Let us have a look at how certain movements of Kazak dance reflect the vision of the world. For example, in Kazakh dance there is a hand movement called “ainalma” – the rotation of wrists.

Moldakhmetova A.T. in her PhD thesis [3] quotes the thought expressed by Zaurbekova and Djumanova: ‘The movement of the hands of ‘Ainalma’ reflects the cult of the solar deity; the phenomenon circle in the structure of the nomadic worldview specifically expresses the temporal aspect, a twelve-year cycle of mүshel, in which ‘human life is thought of as a transition from one mushel to another, which meant a return to initial state, end and beginning of a new circle in living space at a qualitatively different level. This, figuratively, the structure of the unwinding spiral was the most important element of traditional thinking’.[4]

For example, this dance ‘Erke Kyz’ represents the whole palette of the intricate rotations of the wrists which creates a beautiful pattern of the dance. Graceful movements of arms and wrists, typical for a female Kazakh dance, can be seen in this dance staged by a wonderful choreographer, Zulfia Aubakirova. A. Shankibaeva, the art critic explains the meaning of this movement as follows: “one turn of the wrists, symbolizing the cycle of a full turnover of reception and return of heavenly well-being, having its deep philosophical meaning, is a distinctive feature of Kazakh dance’.[5]

In the Kazakh language, there is the word “aynalayin” – this is how Kazakhs call a person dear to their hearts, denoting their endless love for someone close. Kairbekov B. explains the meaning of this word as follows: ‘In translation, it sounds like ‘I am circling around you!’. This word is associated with the process of treatment by a Kazakh healer – bakhsy, who guarded the patient around him, ‘taking’ his ailment, transferring it to himself, and in this sense, it would be more accurate to translate the word ‘ainalayin’ as ‘I am ready to sacrifice myself in the name of saving you!’[6]

As mentioned above, bakhsy in their rituals used the indispensable attributes of a circle and rotation around a person. The Bakhsy’s worldview is characterized by the idea that the Universe consists of three worlds: The Upper World, where only spirits live, The Middle World, where people, animals, and plants live along with the spirits, and The Lower World, where the souls of the dead go to. Thus, the bakhsy is the transmitter between the world of people and the world of spirits. In the process of shamanic rituals, bakhsy is able to trace the struggle between the dark and the light forces, which will be reflected in his plasticity in the form of movements typical of warriors.

There were folk akyns, singers-improvisers, and folk comedians of the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries, who were known as the masters of dance art.

In connection with the magical beliefs of people about the transmigration of the soul to animals, in the bakhsy dance we can see some movements that convey the habits of animals and birds. Some Kazakh dances are based on the imitation of the habits of animals, for example: ‘Koyan bi’ (dance of the hare), ‘Burkit bi’ (dance of the golden eagle), ‘Ayu bi’ (dance of the bear), ‘Orteke’ (dance of the goat, trapped in a pit), etc.

For example, you can see the dancers dancing in animal masks at the beginning of the Seryler saltanaty dance performed by the students of the Kazakh National Academy of Choreography (music by the folk ethnographic ensemble Khassak; choreography by Anvara Sadykova and Almat Shamshiev). The dance culture of Kazakh people was especially developed in the work of steppe performers – Sala and sera. Their work can be considered as a ‘theatre of one actor’; they were universal performers and naturally talented actors: singers, composers, storytellers, magicians, dancers, wrestlers, jugglers, etc. They performed in auls, where they entertained their audience with various kinds of performances.

There were also folk akyns, singers-improvisers, and folk comedians of the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries, who were known as the masters of dance art. For example, Berikbol Kopenov (1861-1932) – a singer, dombra player, amateur artist, kyuishi, poet, dancer, nicknamed Agash-ayak (‘wooden leg’) – was famous for his ability to dance on stilts. According to Abirov and Ismailov[7], Kazakh researchers of dance history, Shashubai Koshkarbayev (1865-1952) – a Kazakh akyn, poet and composer – performed his songs to the accompaniment of an accordion and dombra.

He used to jump on a horse before the performance and demonstrate a horseman dance at full speed, standing in the saddle, then jumped to the ground and danced around horse. He was also a master of a comic dance called Orteke (literal translation of Orteke is ‘a goat caught in a pit’).

D. Abirov also mentions the names of folk dancers of the first quarter of the XX century: Akhmet Bersagimov, who was nicknamed Zhyndy Kara, who performed dances and satirical pantomimes, where he ridiculed bays (local wealthy governors) and feudal lords, for which he was nicknamed ‘zhynda’ (fool). Zarubay Kulseitov was famous for performing the dances ‘Koyan bi’ (hare dance), ‘Koyan men burkit’ (hare and golden eagle). Doskey Alimbaev (1850-1946) – Kazakh akyn danced ‘Utys bi’ (dance-competition), as well as ‘Kusbegi – dauylpaz’ (hunter with a bird and a drummer).

The name of Iskhak Byzhybayev is especially close to us. A unique chronicle has come down to us, where he performs the comic dance ‘Nasybaishy’, surprising in its originality, at the folk-dance festival in 1936 in Moscow. The plot of the dance, colorful movements, which are sometimes striking in their complexity, are vivid evidence of the presence of a unique dance culture among Kazakh people.

The first national performers and choreographers led the way to the development of Kazakh stage dance by creating a number of wonderful choreographic works that later made up the golden fund of the national choreography. These are productions by Shara Zhienkulova, Aubakir Ismailov, Dauren Abirov, Yuri Kovalev, Zaurbek Raibayev, Bulat Ayukhanov, Mintay Tleubaev, Eldos Usin, Zhanat Baydaralin, Olga Vsevolodskaya-Golushkevich, Gainikamal Beisenova, Gulsaule Orumbaeva, Aigul Tati, etc.

Today in Kazakhstan there are four ballet theatres with a unique repertoire – the Kazakh National Opera and Ballet Theatre named after Abai (established in 1934), the State Academic Dance Theatre of the Republic of Kazakhstan under the direction of Bulat Ayukhanov (established in 1967), the State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre ‘Astana Opera’ (established in 2013), State Theatre ‘Astana Ballet’ (established in 2012). Theatre of contemporary dance ‘Samruk’ (established in 1998), State dance theatre ‘Naz’ (established in 1999), State Dance Ensembles ‘Saltanat’ (established in 1955), ‘Altynai’ (since 1985), dance ensembles at philharmonic halls in the regions of Kazakhstan, etc.

And this list goes on and on … Our mission is to preserve this unique cultural heritage and look for new ways of developing our national choreography which currently absorbs the best traditions of classical and contemporary dance as well as the heritage of our ancestors.

And answering your question, I can say that without the presence of the deep national song, music and dance traditions that have been formed for centuries in the Kazakh steppe, the ability to be open to other cultures, absorb and accept what is close in spirit, in moral values, we could not present today what we call the Kazakh national culture as a whole.

Since the beginning of 2010, the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ (Black Pacer) became widely known. The dance quickly spread on the Internet and became a popular piece for flash mobs, advertisements, numerous online lessons, and one of the favorite dances for weddings. The accompanying song with a light, easy and cheerful text, full of humor, appealed to people of all ages. According to some Internet sources, Arystan Shadetuly, a native Kazakh from China, who returned to his homeland in 1995, is considered the ‘revivalist’ of dance in Kazakhstan. How can you explain the origins of this dance?

I have great respect for Arystan-ata. We invited him to take part in the making of our documentary ‘Kazakh Dance’. He is an excellent performer of the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’: a plastic, musical, original dancer. In my opinion, of course, Arystan Shadetuly played a big role in the popularisation of this dance in Kazakhstan.

However, it should be emphasized that on the territory of modern Kazakhstan, the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ was also performed in Soviet times, but under a different name ‘Buyn bi’ (dance of joints).

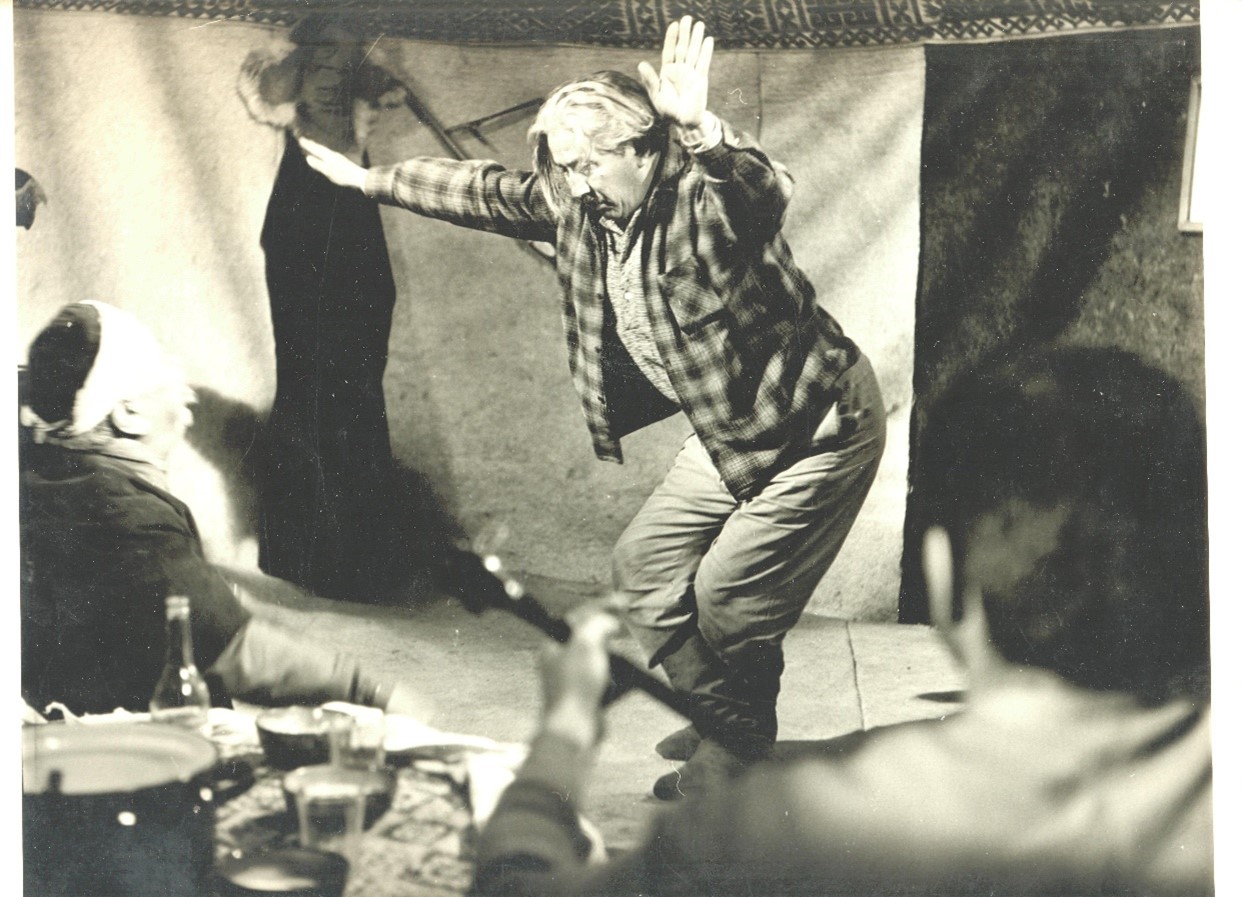

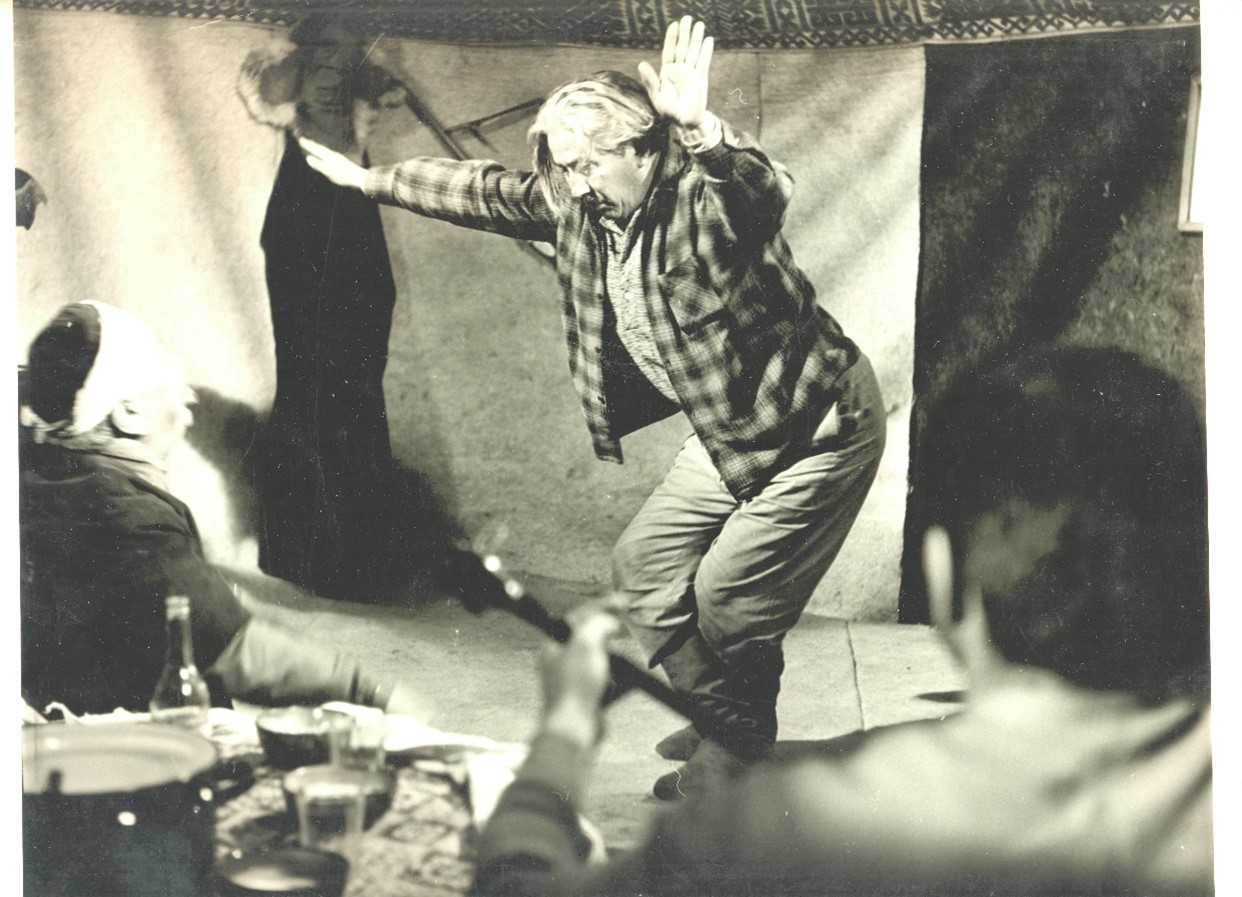

The repertoire of the aforementioned ensemble ‘Altynai’ to this day includes the dance ‘Buyn bi’ staged by Olga Vsevolodskaya-Golushkevich, who created her dances under the close attention of the ethnographer Uzbekali Dzhanibekov. And the performance of this dance among the people is proved by the following episode, when Uzbekali Dzhanibekov met two tractor drivers living in the Narynkol district of the Almaty region, skilfully performing the ’Buyn bi’ dance. It was their performance of this dance that inspired the creation of a choreographic composition for the ‘Altynai’ ensemble under the accompaniment of a kyui (folk instrumental musical composition).

Today the elements of the ‘Buyn bi’ dance are included in the main program of the Kazakh male dance, as the section ‘Buyn oinatu’ – ‘The game of joints’.

What is common and fundamentally different between these two dances – ‘Kara Zhorga’ and ‘Buyn Bi’?

First, we should think about the very name of the dance and its meaning. ‘Kara Zhorga’ is translated from the Kazakh language as ‘black pacer’, i.e., in this dance, the performers depict horsemen prancing on pacers. In the book ‘Kazakh folk dances’ written by D. Abirov and A. Ismailov (1961), the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ is described as follows: ‘The dance shows the agility, dexterity, cheerful enthusiasm of a horseman who has completely mastered the art of horse riding. This dance was popular among the people in various versions and under various names: ‘Kara Zhorga’, ‘Zhorgalau’ (a ride on a pacer), ‘Zhorgany elikteu’ (imitation of a pacer)’.[8] They mention that the folk melodies were performed on dombra and used as an accompaniment to the dances ‘Kara Zhorga’ and ‘Bozaigyr’. In 1928, the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ (recorded by Aktay Mamanov) was performed in Petropavlovsk on the stage of the People’s House.[9]

Further, Shara Zhienkulova in her book ‘The Secret of Dance’ (1980) describes the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ as a ‘group male dance [that] depicts an equestrian sport. The number of dancers can be four and more. Each performer holds a kamcha [a whip] in his right hand’.[10]

D. Abirov in his later book ‘History of Kazakh Dance’ (1997) provides an analysis of the movements of ‘Kara Zhorga’ as it was performed in the play ‘Ayman-Sholpan’ in 1934, staged by Ali Ibragimov (1899 – 1959), a famous Central Asian dancer and choreographer, known under pseudonym Ardobus. A. Ardobus puts on ‘Kara Zhorga’ as the imitation of horse riding – sports games of young people on horseback. The choreographic text consisted of energetic jumps with waving a whip (kamcha) over the head, jumps with a back bend of the body, and springy small bounces in place. The dance was designed to be performed by one person’.[11]

Both D. Abirov and A. Ismailov in the description of the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ specifically presented such movements as ‘zheldirme’ (trotting), ‘moldas’ (rocking chair), ‘tebingi’ (spurring), ‘shalys’ (hook), ‘Monkime’ (jumping with clenched knees, ‘shabys’ (gallop), ‘ytymaly aynalma’. All these movements are unique and distinctive, perfectly conveying daring, agility, strength, character, manner of a male dance. These movements were included in the main male Kazakh dance study program.

Abirov explains the popularity of ‘Kara Zhorga’ by historical reasons: ‘For Kazakh nomads, life without a horse was unthinkable. […] The horse was an indispensable form of transport for moving across the vast steppe and mountains. Thanks to his horse, the Kazakh participated in battles, in all kinds of national games, on it he looked for pastures, escaped from disaster. The people admired the good horse. Obviously, therefore, in legends, heroic poems and legends, the people praised the horse as a faithful friend’.[12] ‘Obviously, the birth of the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ is associated with the observation of people at the unusual pace of the pacer, differing in trot or gallop from other horses. Fractional kicks of legs, rhythmic clatter of hooves, swaying from side to side of the head, bursts of mane, swaying of the croup created the impression of a dance. […] .. Therefore, in the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ we find movements reminiscent of a pacer’s running and swaying shoulders.’[13]

Based on these works of the classics of Kazakh choreography, we appreciate that the name of the dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ still meant a somewhat different dance in its form, in contrast to the one that is now universally performed under this name. We are convinced that today’s dance ‘Kara Zhorga’ was called by us as the dance ‘Buyn bi’ (the dance of joints) in the past. And this name more accurately and more specifically defines the movement behavior of the performer. The dancers actively engaged the joints of different parts of the body, particularly the joints of fingers, wrists, arms, and shoulders as well as their knee joints and ankles. Their performance was based on a momentary improvisation of a shaman who would express his feelings and emotions through his body movements.

Analyzing the nature of the dance movements, which we call ‘Buyn bi’, one can clearly trace its ancient origin, and its connection with the Bakhsy culture. Circular, sharp and expressive movements of the joints are a distinctive basic element of this dance. Through such plastic, one can see the ritual dance of bakhsy, whereby he communicated with the spirits. The other function also traced here is a healing one. Each element of ‘Buyn bi ‘was meant to awaken the body and increase blood circulation to increase the inner heat and energy to perform his shamanic rituals.

‘Kara Zhorga’ was known and danced by our ancestors as ‘Buyn bi’ – ‘the dance of joints’ originated from Bakhsy culture and shamanism.

This established lexicography of traditional dance movements passed into the culture of unique steppe performers, who conveyed different emotions through the musical accompaniment of dombra. The performer danced both in the yurt and in the open air. Arystan Shadetuly shared a very interesting observation during the filming of the documentary ‘Kazakh Dance’: “The performer danced in the center of the yurt. His ‘stage’ size was equal to one ram skin’. Therefore, the dominant steppe monoculture was vividly embodied in the dance genre as performed by a single dancer (although this does not at all deny the mass performance of dances).

This watercolor sketch by Cheredeev – the Russian artist-topographer, who visited Kazakh lands as part of the expedition of the Russian Geographical Society in 1854 – is an illustration of his opinion. Cheredeev ‘s sketch ‘Yurt of the Sultan ‘Davlet-Gerei’ shows a Kazakh man dancing in a limited space, in the middle of the yurt.[14]

To summarise the origins of ‘Kara Zhorga’ which is well-known and popular today, I would like to reiterate my point that this dance was known and danced by our ancestors as ‘Buyn bi’ – ‘the dance of joints’ originated from Bakhsy culture and shamanism. The ‘Kara Zhorga’ dance in the interpretation of the Kazakh dance classics (D. Abirov, A. Ismailov) is primarily a ‘black pacer dance’ depicting a horseman prancing on pacers. I would say that the name ‘Kara Zhorga’ was ‘borrowed’ to name the dance that was actually known to our ancestors as ‘Buyn bi’. It is especially noticeable in the dances performed by these two Kazakh gentlemen who are amazingly flexible and acrobatic regardless of their respectable age – Orazbai Bodauhanuly and Shedet Maikanuly. Do you know why they are so flexible and agile? Because they regularly stretched their joints by dancing ‘Kara Zhorga’, which our ancestors used to call ‘Buyn bi’!