Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov

This week we would like to recommend reading a beautiful volume on “Campaigning on the Oxus and the Fall of Khiva” written by Januarius Aloysius MacGahan (June 12, 1844 – June 9, 1878), who was an American journalist and war correspondent working for the New York Herald and the London Daily News.

One may remember a famous saying by 16th U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, “And in the end it’s not the years in your life that count; it’s the life in your years”. In this sense, the 34 years that MacGahan lived were full of most interesting adventures and explorations. Born near New Lexington, Ohio in 1848 MacGahan had an extraordinary personality.

His father was an immigrant from Ireland who had served on the Northumberland, the ship which took Napoleon into exile on St. Helena. MacGahan moved to St. Louis, where he worked briefly as a teacher and as a journalist. There he met his cousin, General Philip Sheridan, a Civil War hero also of Irish parentage, who convinced him to study law in Europe. He sailed to Brussels in December 1868.

MacGahan did not get a law degree, but he discovered that he had a gift for languages, learning French and German. He ran short of money and was about to return to America in 1870 when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Sheridan happened to be an observer with the German Army, and he used his influence to persuade the European editor of the New York Herald to hire MacGahan as a war correspondent with the French Army.

MacGahan’s vivid articles from the front lines describing the stunning defeat of the French Army won him a large following, and many of his dispatches to the Herald were reprinted by European newspapers. By the age of twenty-seven, he was a celebrity.

When the war ended, he interviewed French leader Léon Gambetta and Victor Hugo. In 1871 MacGahan was assigned as the Herald’s correspondent to St. Petersburg where he also learned Russian language.

In 1873 MacGahan travels to Central Asia on a horseback. In the preface of his book, MacGahan thanks his good friend Eugene Schuyler for the assistance rendered on his way to Central Asia. Avid readers of the Abai Center will remember that Schuyler was a prominent U.S. diplomat and acted as a charge d’affaires of the United States to St. Petersburg from where he traveled all the way to Turkestan and shared his observations along the way.

Beyond doubt, many Western travelers of late 1800s have shared their studies of Syr Darya. Amongst them, MacGahan’s depiction perhaps is the most flamboyant one. He says, “the Syr is the most eccentric of rivers, as changeable as the moon, without the regularity of that planet. It is a very vagabond of a river, and thinks no more of changing its course, of picking up its bed and walking off eight or ten miles with it, than does one of its Kazakhs, who inhabit its banks”1.

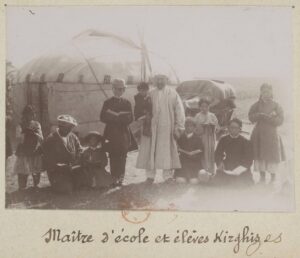

Nomadic yurts have long been a subject of interest for many Western travelers. Whereas there are plenty of accounts describing these yurts, MacGahan contributes to this knowledge by sharing his own experience of witnessing how they are assembled. In his words, “I was very interested in watching the women set up the tents, and the speed with which they accomplished it”2. The framework of the Central Asian tent, he continues, is composed of a number of thin strips of wood six feet long, loosely fastened together in the form of vine-trellis; this frame opens out and folds up compactly, so that it may be placed on a camel. The sticks forming this frame are slightly curved in the middle so that upon opening out it naturally takes the form of a segment of a circle. Four of these frames complete the skeleton sides of the tent. On the top of this are placed some twenty five or thirty rafters, curved to the proper shape, the upper ends of which are placed in a hoop, three or four feet in diameter, serving as a roof tree3.

MacGahan also shares his memories of being hosted by the chief of local aul, where he ordered a yurt to be set up for his own especial use. The author says that the yurt was nicely carpeted and provided with several soft, bright colored coverlets and cushions, which were deliciously luxurious.

MacGahan also very accurately describes the nomadic way of life of the Kazakhs. In his view, it was very peculiar. The three winter months, he says, are passed in mud habitations on the banks of some river or small stream. When the snow begins to melt, they start out on their yearly migrations, he adds. For nine months they never stop in one spot more than three days, and all the time live in tents. They continue their march often until they have travelled three or four hundred miles; then they turn around and go back exactly the same route, reaching their winter quarters again when the snow begins to fall.

To anybody acquainted with their habits of life, MacGahan explains, there does not seem to be the slightest system in their movements. They have a system nevertheless, concludes the author and continues further by saying that every tribe and every aul follow year after year exactly the same itinerary, pursuing the same paths, stopping at the same wells as their ancestors did a thousand years ago; and thus many auls whose inhabitants winter together, are hundreds of miles apart in the summer. The regularity and exactitude of their movements is such that you can predict to a day where, in a circuit of several hundreds miles, any aul will be at any season of the year. A map of the desert, showing all the routes of the different auls, if it could be made, would represent a network of paths meeting, crossing, intersecting each other…

Not only he accurately describes the movements of auls, but also shares some insight of Kazakh daily routine. He says that in the morning, first, the sheep, goats, and camels were milked before being sent off to the desert to pasture. Then the carpets and felts were taken out and beaten, and re-arranged in their places, together with the other household implements4.

In addition to describing household routines, MacGahan also shares his personal stories and feelings about living among the Kazakh people. In his own words, MacGahan would remark that his sojourn with the Kazakhs left a most favorable impression upon him. “I have always found them kind, hospitable and honest. I spent a whole month amongst them; travelling with them, eating with them, and sleeping in their tents. And I had along with me all this time horses, arms, and equipments, which would be to them a prize of considerable value. Yet never did I meet anything but kindness; I never lost a pin’s worth; and often a Kazakh has galloped for or five miles after me to restore some little thing I had left behind”5.

“The Kazakhs possess to a remarkable degree

of the qualities of honesty, virtue and hospitality”

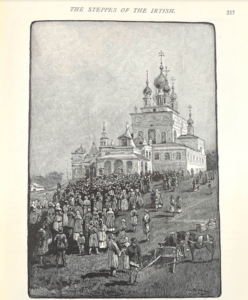

Besides enticing stories so skillfully told by MacGahan, we are sure that our readers will enjoy looking at the beautiful illustrations made by prominent Russian war artist Vasily Vereshchagin, whom MacGahan met during his journey to Central Asia and became friends with. The story of MacGahan himself is anything but ordinary and so is his journey through the heart of Eurasia – Kazakh steppes.