Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov

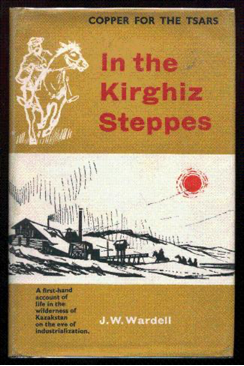

Avid readers of the Abai Center are well acquainted with the works of Western scholars and journalists who travelled across the Kazakh steppes from 1800s to 1900s. This volume by John Wilford Wardell presents our readers with a unique opportunity to take a glimpse into a bygone era beyond the nomadic heritage.

First published in 1961 in London, the book introduces us to the author’s travels through the Kazakh steppes in his capacity of staff at the Spassky Copper Mine Ltd. from 1914 to 1919. To reach Spassky from London, Wardell covered a distance of 4.400 miles and travelled for sixteen and a half days, arriving at his destination on June 2, 1914 on his twenty fifth birthday.

Years later after his travels, Wardell notes, “As I was one of the last Englishmen to visit Kazakhstan – for a few, if any, have been there since the Soviet Union was established – and as the conditions of life there perhaps altered forever, I think that is most desirable to save for history of this account of the inhabitants of the country and how they have lived hundreds of years before the great change. To this I have added a description of the country, its climate and other characteristics, and a record of the reactions of those five eventful years on the life of a British community…”1.

The Spassky group of mining properties, Wardell explains, in two camps of which he was to live for five years, was situated in the old province of Akmolinsk, except for the new camp of 1916, which was just within the old province of Semipalatinsk, but now all for camps are in the province of Karaganda. The main camp and smelting works were at Spassky Zavod where Wardell lived for the first two years.

The author shares that Spassky had a population of about 3000 of whom perhaps two thirds were Kazakhs, and the total population of three camps approximated to a similar number. The main inhabitants of these four villages, according to Wardell, with the exception of a few traders who lived at Serechka (over the Creek) in Spassky, were employed by the Company, so that work was found for about 300 Russians and 1500 Kazakhs. The British staff, which numbered eighteen in 1914, was reduced by war and other circumstances to fourteen in 1915, ten in 1918 and eight in 1919.

Soon after Wardell’s move to Spassky, his wife joins him and they fully settle down in their new abode, growing accustomed to the new life and surroundings of the camp. Together they purchase a horse and name it Ginger and below are some illustrations of Wardell’s spouse riding around the Spassky area. The author recalls this experience saying that “fresh from the English landscape, it took us some time to get used to the lack of trees in the Spassky area, but when we did become accustomed to the steppes – and it is marvelous how soon this became a fascination…”2.

In addition to riding, Wardell writes, other summer diversions were tennis on the hard courts near the staff house, swimming in the big pools of some of the streams and picnics in the hills. During the winter months, Wardell recalls, there was still riding, and in addition they had sleighing and skiing for outdoor sports. For winter evenings there were rounds of bridge parties, billiards in the club room attached to the general manager’s house, monthly dances and sing-songs as well as jolly series of house – to – house dinner parties at Christmas time.

At times Wardell and his colleagues would go after geese and duck, generally to a lake about twenty miles from Spassky – near the company’s ironstone area – which he jokingly says did not deserve its name Sasik Kara Soo (Stinking Black Lake) or arrange weekend expeditions.

Karaganda, Wardell shares, being only twenty six miles away, was visited several times during his stay at Spassky, mainly by light carriage or sleigh. He also visited Oospensky four times during the first two years, and each trip, in his opinion, was different and interesting on its own. The first was made in the summer by tarantass, with two changes of horses at the company’s pickets and provided with an opportunity to witness a splendid scenery.

With a great deal of interest during his next trips to Oospensky, Wardell shares reaction of local Kazakhs towards the company vehicle that they excitedly described as Shaitan araba (devil’s wagon).

In August 1915, Wardell writes, their first son was born and it was the first English child to be born at Spassky since the properties came into British hands ten years earlier. Dick was four years old when the couple left the mines.

During the autumn 1915 Wardell travels to Akmolinsk to visit a dentist. It was his first trip to the capital of the province and they made this journey, a distance of 185 miles, in twenty four hours using the company’s covered tarantass and changing three horses at each post station.

Wardell enjoyed his time in Akmolinsk as well as the social life there that included instrumental and vocal concerts, dances and card parties, and as he later recalls, sleighing in winter, picnics and riding in summer, eating and drinking anytime.

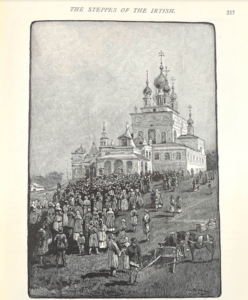

Akmolinsk, Wardell notes, stands in the great agricultural plain on the north bank of Ishim and had a population of ten thousand people at that time. The great Byzantine cathedral stood in the middle of the huge square in the center of the town, and around three sides of the square were public buildings, private houses, two or three hotels and a theater which was an opera house or a concert hall on occasion. Along the south side of the square there were shops and behind this was the bazaar, a large open space surrounded by shops and warehouses. Opposite the bazaar, Wardell says, was a third open space in which stood two mosques.

Wardell also describes other properties of the company. For example, he notes that the Atbasar properties of the company were situated about 500 miles to the west of Oospensky mine and comprised copper mine at Djezkazgan and colliery at Baikanoor, both of which were well developed and were already producing ore and coal, and reduction and smelting plants in very early stages of Karsakpai. The carbonate copper ore in this mine, Wardell explains, is very reach and the deposit is known to contain at least three million tons3.

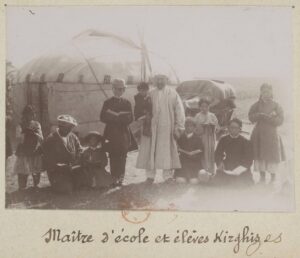

Interestingly, Wardell shares not only his observations of the Spassky area and work-related findings, but also takes time to get acquainted with the local population by studying history and traditions of Kazakh people. In his book, he says that the name Kazakh mean “wanderer”. He also explains their origins saying that “Kazakhs have been divided into three hordes, which wandered over more or less defined areas and carried tribal names which indicated their origins. The Great and Little Hordes inhabited the districts east of Lake Balkhash and west of the Sea of Aral respectively, and the Middle Horde, which is now most numerous, occupied the country between. The Kazakhs of the Great and Middle Hordes are of Kirat and Naiman tribes respectively”4.

According to Wardell, as a race the Kazakhs are adventurous and free spirited, and like all of the nomads they do not take kindly to being settled in one place. They are good natured and hospitable with friends and peacefully disposed towards stranger. They are extremely fond of children. He also adds that “altered political and economic conditions during the past forty years will have modified these characteristics somewhat, but the personalities inherited by the Kazakhs through countless centuries cannot be greatly altered by such a short period of change”5.

Speaking of Kazakh traditional cuisine, Wardell says that curds and cheeses were eaten more than meat during summer, and Kazakh women claim to make about thirty kinds of milk foods from hard sheep’s cheese to koumis, or fermented mare’s milk.

The Kazakh culture, Wardell explains, like that of Turko-Mongolian people, was based on the horse, because horses were essential to the existence of these nomads, whether for fighting their enemies, herding their flocks, transporting their families or financing their economics, and his steed was the Kazakh’s best friend as well as his most faithful servant.6

Wardell also describes the strong family values that existed among the Kazakhs saying that divorces were practically unknown in Kazakhstan and Kazakh wives have always been important members of their nomadic communities, responsible for many duties.

With a great interest, the author speaks of Kazakh bards and poets who were always sure of good entertainment and festivities. In his words, they spent all their lives learning and telling the sagas covering the lives of national heroes – legendary and historical, ancient and modern.

In addition to this, Wardell adds, Kazakhs were very keen sportsmen and they would go all length to obtain a shot gun and ammunition.

To conclude, we hope our readers will enjoy this volume by John Wilford Wardell for it represents a new and fresh perspective on the Kazakh steppes whilst also sharing some aspects of the traditional nomadic life. It is beyond doubt one of the most fascinating stories of its time, unveiling how one of the most industrial regions of modern day Kazakhstan looked like in the years following the WWI and how one of the first British enterprises operated in the country.