The heir to the Swiss watch dynasty, the traveler Henri Moser, was born on May 18, 1844 in St. Petersburg. His father Heinrich Moser was a famous watchmaker in the Russian capital, owner of watch shops and a wealthy estate. At the age of five, Henri was sent to Schaffhausen in Switzerland. Here he received his primary education followed by a bachelor’s degree in Geneva. Moser joined the Swiss cavalry where he served as a lieutenant (1863), he then became an adjutant to the Chief Inspector of the Swiss Army (1864). In 1865, Henri returned to Russia1. His father strongly wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, but Moser was drawn to exotic countries and long journeys. In search of adventure, Moser first visited Siberia in 1867. In 1868 he arrived in Russian Turkestan. The enterprising Swiss man was, among other things, driven by a desire to engage in the trade of silkworms, which were an extremely popular and expensive goods at the time. His first trip to trade silkworms was unsuccessful due to various circumstances, but especially because of the Russian administration’s ban on exporting silkworms from Turkestan.

Subsequent trips by a Swiss traveler were much more successful. In 1869 Moser went on his second voyage through Central Asia, and in 1882-1883 he made his third voyage. From his travels, Henri Moser brought a huge collection of artifacts, such as jewelry, clothes, shoes, and dishes, all of which were exhibited at numerous exhibitions in Europe, ultimately teaching Europeans much about the rich culture of the region. Additionally, Moser presented his collection of Central Asian art and cold steel to the Musée d’histoire de Berne, where it is still housed today.

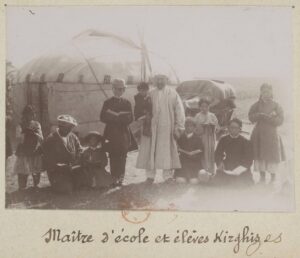

Subsequent to these momentous voyages to Central Asia, Henri Moser begins to publish in the Geneva newspaper, and is elected an honorary member of the eight geographical societies. At one meeting of the geographical society in Paris, he makes a detailed report on his journey in Central Asia.2 An illustrated book about this journey “Through Central Asia – the Kirghiz steppes, Russian Turkestan, Bukhara, Khiva, The Land of Turkomans and Persia” (A travers l’Asie Centrale. La steppe Kirghize; Le Turkestan russe; Boukhara; Khiva; Le pays des Turkomans et la Perse) was published in the autumn of 1885 by the Paris publishing house Plon. A whole chapter in this luxurious edition is devoted to the nomadic peoples of the steppes—the Kazakhs3. Here, I present some of excerpts from the chapter “Kirghiz Steppe”, translated from French, that tells about the life and culture of the Kazakhs of the 19th century:

***

From Orsk on, the appearance of the country changes completely. We enter the steppe, dotted with more villages; it is an immense plain, the domain of the nomadic Kirghiz. After the snow melts, this part of the steppe changes into beautiful pastures that feed countless herds- the wealth of these nomads; but soon the blazing sun of the East burns this vegetation, and the aspect of the country, and the laughing in spring, becomes arid; it is not any more but a black and sad plain.

I had previously travelled through the vast plains of Central Asia at different times of the year and seen them covered with snow by the “buran” (blizzard), which sometimes buried entire caravans under a frozen shroud, so they are frightening and gloomy. The temperature there varies from 30° below zero in winter to 35° heat in summer. This is the homeland of the Kirghiz, a homeland that in its bizarre improvisations sings songs of love and commands poetic attraction.

The Turcoman, Karakalpak, Uzbeg, Kaïzak and Kirghiz, who inhabit the immense Aralo-Caspian depression, differing more between one another by their physiognomy and morals than by their dialects, which are all related to the Turkic language. The Kirghiz are the most numerous; they are divided into Kara-Kirghiz, or Black Kirghiz, spread throughout the Altai Mountains, from the Thian-Chan to the south of Lake Issy-Koul, and Kaizaks, or Kazaks; these, numbering over one million, are essentially nomads. They wander through a land that is difficult to define, which stretches from the Urals to Lake Balkac4 and from Amu Darya to the borders of Siberia. Who are these Kirghiz and where do they come from? It seems that they themselves do not know. They claim to be descended from forty virgins (kirk, forty, etkiz, virgin) and come from the borders of China; but they can’t say when they first emigrated to the steppe. The first regularly organized tribe was the “little horde”, descended from three families, or kibitkas, Alimulin, Baiulin and Jeti.

Dress of a Kirghiz-Kazakh Woman. “Burk” Turkish, a Fur-Trimmed Hat

The Kirghiz wear skin or velvet pants, whose color disappears under the embroidery then a “bechmet” or jacket, and finally the “khalat”5, a kind of robe without pockets, with sleeves that are disproportionately long and very wide at the top shoulders and narrow at the bottom extremities. This ‘khalat’, which for the rich is often made of silk or velvet and covered with embroidery, is often simply cotton or wool for the poor. The great belt of leather, for which the poor man replaces with a belt also made of cotton fabric, tightens this garment at the waist and hangs a satchel on it, filled with a bag of gunpowder for an accompanied gun, or paired with a knife.

The Kirghiz shave their heads, but always cover them with a small round cap, sometimes richly embroidered. In summer they tape around their heads a handkerchief bought from Russian merchants, which resembles a turban. Often we meet them, in both summer and in winter, wearing a conical cap lined with foxskin or of lamb; more rarely they wear a white felt hat, offering a striking resemblance to the pointed hats that our children enjoy making do with a triangularly folded newspaper, and whose wide edges, raised from the front, imitate two horns. This headgear is sometimes tall, sometimes low, and it gives the wearer the baroque look.

Dress of a Kirghiz-Kazakh Woman. “Saukele” Turkish, a Ceremonial Hat

Women, reminiscent of the Mongolian type, are better made than men; but their costume differs very little from that of their husbands. They wear a khalat made of cotton or Bukharian silk of bright colors, pants and boots. Young girls let their braided hair flow and wear a cap of fur, adorned with flowers, feathers and beads. What characterizes the costume of a married woman, who never shows her hair, it’s a big white scarf that she wraps around her head and is tied to the lower part of her face and often the bust. Multiple braids of a young girl are mixed with ribbons and coins, but to extend the hair girls often skillfully use horsehair.

Kirghiz-Kazakh Wedding Rites. Ironing Hair

Once married, a young woman devotes herself to her family and says goodbye to beauty products and games. As soon as a child is born, its mother washes it with plenty of water for forty consecutive days, after which he shall be pure and now exempt from any ablution for the rest of his or her life. Until the age of ten years, the costume of children for both sexes is reduced to its most simple expression; the parents simply shave their heads, and they are typically naked.

The Kirghiz, who refer to themselves as a “kazak” (wanderer), are nomadic par excellence; all the attempts to accustom to a sedentary life have failed, except on the confines of Russia, where they now resign to living in a house that they reluctantly built for themselves.

This child of nature only feels truly happy in the middle of the boundless steppe, where nothing stops the gaze. His favorite dwelling place is the yurt or “kibitka”, which women erect or fold in very little time and easily loaded on the back of a camel. These yurts, securely moored to large stakes driven in the strongest storms; if it becomes too cold, a new blanket can be placed over the first one, and dirt or snow can be piled around its base. The inside of these dwellings is decorated with carpets, clothing, weapons, household utensils and horse harnesses. The bed is made up of a few pieces of felt and blankets, and is found in front of the entrance; it is also the place of the house mistress.

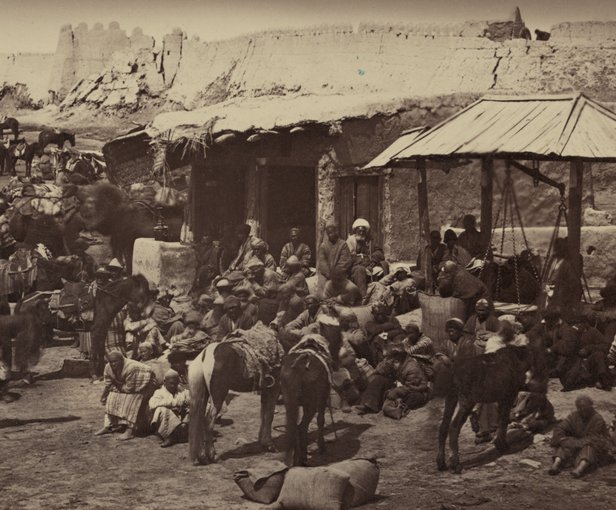

Syr Darya Oblast. Aulie-Ata. Horse Bazaar

The Kirghiz are frank, hospitable and brave. They spend their lives transferring their penates and herds from one pasture to another. In the summer they herd them up to the limits of Siberia, an in the winter, herd them down to the banks of the Amou river. They set up their “aouls” (campsites) near the springs, and stay in one place as long as their cattle find food. The walk around an aoul on a trip is very interesting. The men, usually armed, precede and inflate the long lines of camels carrying their families and their penates. Then come countless flocks of sheep, the “taboos” (herds of horses), then other camels again; they usually stop near springs. Only one hour after arrival, the village is improvised, the women set up the tents, and big pots hang above the fire.

Even though these people are Muslim, it is rare to see two women under the same tent. The rich give themselves the luxury of several wives, but they take care to make them live in different aouls, which allows them to console themselves from a distance with another wife, as soon as something goes wrong in their married life. This is maybe the reason there’s no steppe and no divorce. Neither emancipated, nor misunderstood woman.

The most respected tribe of Kirghiz is the Adai. This tribe wanders the steppes between the Caspian Sea and the Khan state of Khiva. They have armed “barantas”, which are not to be confused with the “alamanas” of the Turcomans. But, to give readers an idea of the real Kirghiz steppe, I commit them to follow me a few years back, when at twenty I was roaming this steppe, light-hearted, ready for adventures. With my empty purse I travelled light, but I was ready to welcome any new impression with enthusiasm.

Illustration of the Kirghiz-Kazakh family.

It was still the time of the Sultans. At that time, the steppe was divided into three rays, each having its “pravitel”6 or Kirghiz governor, at its head. Bay-Mohammed ruled the North, Ian-Tourin ruled territory between the Volga and the Urals and Suleyman-Taukin – the steppe of Orenburg. I had won Suleiman’s friendship, and I was hosted for a long time by this direct descendant of Khan Abul-Khair, who had, as such, serious rights to the steppe khanate. The elder branch was extinguished, while he was the successor to the youngest branch. The last khan had only one son, Ibrahim. Prince Ibrahim was elevated at the Corps des Pages in St. Petersburg. Unfortunately, he died young, regretted by all the Kirghiz in the steppe. The Kirghiz aristocracy, whose khan was the head, occupied then twelve hundred or so kibitkas;7 all the members of this great family, allied only with each other, claim to be descended from Abul- Khaïr, and even their children know the names of their ancestors.

Suleiman Sultan, a clever young man, had frankly attached to me during my stay in Orenburg. Seeing that I was studying the Kirghiz language with zeal, he offered me to come with him to his aoul. On a beautiful day, mounted on excellent Kirghiz amblers, we approached the immense plain.

Central Asian Funerary Customs. Preparation for a Kyrgyz Burial

When we arrived at the village, our horses stopped in front of the largest tent, which had been transformed into a reception hall. The most agreeable warmth awaited us.

“Salem aleikom,” my host said to me, hugging both of my hands, as we crossed the threshold of his “home”. The white felt of the yurt is covered with rich carpets, on which are suspended English weapons, as well as the national weapons – aïbalta, as well as rich harnesses of horses. The thick felts stretched out on the ground, also covered with brightly colored carpets; in the center is a large fireplace with burning coals. We sit down orientally on cushions placed opposite the entrance. Little by little, the yurt fills up with people: the brothers, the friends and relatives of the sultan.

A line of servants makes its entrance in the tent, each one carrying a large tray which they deposit at our feet. It’s a feast capable of satiating a squadron, and yet only sultan and I were eating. An officer, armed with a knife, sliced the meat, and then shared them with his fingers on the plate. There’s sheep and horses, it’s not the old nag that our poor people eat in Europe, it’s the succulent meat that we keep for special occasions; but the most appreciated dish, the one that only appears at feasts, it’s the young camel. Camels are served with rice mountains prepared with carrots and raisins. This is the national dish, which the Sarte calls palau, pilaou or pilaf.

Politeness requires you to stuff yourself with food. If I show any hesitation in it, Suleiman, with his hand, chooses the biggest pieces to put them to my mouth. When, to end this Pantagruelian meal with dignity, we were offered a tea with fat of sheep diluted, I feel exhausted.

Our spectators, left the yurt during the meal, and I could take out of my reserves a few bottles of “nalifka”, this liqueur so dear to the Kirghiz and which the sultan drinks behind closed doors, like most Muslims. Suleiman, who has become very familiar, thanks to my bottles of vodka, bestowed upon me the greatest honor that may have been granted to a Christian, he expressed the desire to introduce me to his favorite wife.

Kirghiz-Kazakh Wedding Rites. Inspection by the Groom

When Fatmé, the sultan wife entered the tent, she dazzled me with her beauty and the richness of her costume. She was a woman in her early 20s, with flushed skin, and admirably proportioned forms. On her head she wore an elegantly red velvet cylinder-shaped headdress, literally covered of precious stones and bordered at the bottom with zibeline. As a sign of her authority, the favorite had an array of egret, heron, and ostrich feathers on her headdress. We stood up at her entrance. After having graciously welcomed me, Fatmé offered me to sit by her side, and seeing that I admired both her person and her dress, a smile of satisfaction showed me her pretty sharp teeth. It is with an obvious pleasure and a very feminine coquetry that she gave me notice of the details of her costume. From the top of her toque the Muslin veils edged with gold fringes fell on the shoulders. A sort of white satin chasuble, trimmed with broad gold braids and gold fringe… This graceful costume was complemented by white silk trousers, very thin, embroidered with gold and tight at the ankle; the boots, very small, red morocco, were also covered with embroidery, and were covered with gold and fine stones.

Fatmé let herself be admired with complacency, candidly receiving the compliments. I compared her teeth to pearls, eyes to the stars, smile to sunrise and face to a Swiss cheese. The last comparison might have been too metaphoric, but the kindly lady was satisfied with my admiration. A married woman would never dare to show her hair, but, wishing to complete the good opinion I had of her, Fatmé wanted me to see her black braids. I touched them delicately, but not without pulling it maliciously enough to make sure it was true or false. Even in Europe, a woman would have been very proud of this hair. A fairly long silence followed and made me feel that my turn had come to give her a good opinion, if not of myself, at least of my country and its female world. So, I wore a medallion around my neck with a portrait of a woman, and I showed it to her.

- “This is your favorite? she said. Is it you who made her image?

- “But no,” I replied, very surprised. – “A painter from my homeland.”

- “This woman does not love you, since she shows herself to another so scantily clad.”

This miniature depicted a European woman in a ballroom, and without knowing it, this girl in the desert had guessed right. Her astonishment was great when I told her that, in our assemblies, all women are dressed as little as possible, and especially when I described our balls, where a woman goes from one arm to the other. But the sultan seemed not to like the turn the conversation was taking. He waved, the door opened to give passage to three young girls “kisdars”, relatives of Fatmé, in complete national costume.

The tallest girl came to my left. I liked her. Her eyes were not big, but expressive; the teeth were remarkably white; she was, in short, a very attractive woman. Her costume was almost similar to Fatme’s. She bore the melodious name Khalisa. After sitting down, she presented me with her two white hands, which I squeezed cordially. We were served tea, sweets, dried fruits, pistachios and almonds, which my neighbor broke with her teeth and then gave them to me.

Syr Darya Oblast. City of Chimkent and Its Types of Street Life. Horse Bazaar

Little by little, the guests appeared in the tent. Two young men, dressed in khalats and white bonnets, came forward in the center of our circle. The first one got down on his knees, a “doumbra”, a kind of mandolin, in hand, to accompany his friend, who, after prostrating himself, sang a lament in the name of my honor. This rhythmic improvisation lacked neither originality nor melody. I showed my gratitude, both to my host for his attention and to the troubadour for his talent.

When the concert was over, we moved on to the games. For this purpose, a khan, or king, was appointed by Suleiman. A crown of gold paper was granted to him, while the sultans wore white turbans.

All of these games were strikingly similar to our games and the people of civilized Europe. Did we take them from the Orientals or did they come to them from the West? I’d say more like the first assumption.

As the evening progressed, the games became more animated and noisier, probably under the influence of the “koumiss” (kumys?) which had been going around, and I realized it was time to retire.

As I was saying goodbye to my charming neighbor, I noticed a ring on her finger, and as I was asking her where it came from, she took the ring off and offered it to me.

- “Take it,” she said – “it’s a poor girl from the steppe, who gives it to you. This is wish of Khalisa.” Me, in my turn, detached an old relic from my watch, and I said

- “You shall give it to the one you love, and I wish that he will be worthy of your love.” What became of that proud Amazon, with whom later on I’ve had so many good rides in the desert? I see her again, on the day I said farewell to her. She is on a horse, one hand on the forehead, the other on the heart. It’s a great memory of the steppe that I’ve just brought back to life. It came back to me like a whiff of youth when writing the name – Khalisa.

Snezhana Atanova

Snezhana Atanova is a PhD candidate at INALCO. Her thesis focuses on nationalism and cultural heritage in Central Asia. She recently finished an IFEAC fellowship devoted to national identity in everyday life in Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. She was awarded a Carnegie fellowship in 2017, in which she explored national identity through the nation-branding initiatives of Russia and Central Asian countries. She earned a Master’s in International Communication from the University of Strasbourg in 2012 and a Master’s from the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations (INALCO) in 2015.

With the exception of the photos of Moser and the Kirghiz-Kazakh family, all photos are taken from the Turkestan Album, which can be found here.

- In Central Asian countries. Henry Moser’s travel experiences. 1882-1883. [В странах Средней Азии. Путевые впечатления Генриха Мозера. 1882-1883 гг.] // Russkaya starina [Русская старина], № 1. 1888 ↩

- In Central Asian countries. Henry Moser’s travel experiences. 1882-1883. [В странах Средней Азии. Путевые впечатления Генриха Мозера. 1882-1883 гг.] // Russkaya starina [Русская старина], № 1. 1888 ↩

- In the 19th century, modern Kazakhs and Kirghiz were called Kirghiz. However, Moser in his essay clearly indicates to Kazakhs in his account. ↩

- Note of translator: this is probably Lake Balkhash ↩

- I used ‘kh’ in the French spelling for all the original Turkish or Persian terms in which the indigenous pronunciation is similar to the Turkish or Persian pronunciation like the German guttural -eh preceded by a, o, u, Dutch -g, Spanish -j or Russian -х ↩

- Note of translator: Pravitl or pravitel is the Russian term for the term leader or chief. ↩

- Note of translator: Kibitka (Russian word) or yurt is a portable, round tent covered with skins (maybe hides or fur?) or felt and used as a dwelling by several distinct nomadic groups in the steppes. ↩