Abilkhan Kasteyev (1904-1972), a Kazakh artist who was born at the dawn of the twentieth century, became the founder of visual arts in Soviet Kazakhstan. Prior to him, Kazakh painting mostly existed in a decorative or applied form. However, the creative spirit of the Kazakh people quickly adopted the norms of the introduced canon, and Kasteyev became the first of a group of Kazakh artists, the chief chronicler—through his watercolor sketches, pencil sketches, and portraits—of the era that grew and developed alongside him.

Today, the name of Abilkhan Kasteyev, who was awarded numerous titles by the Soviet state, is borne by the main Museum of Visual Arts in Kazakhstan, located in Almaty. His own works are preserved not only in Almaty, but also in Moscow, at the Tretyakov Gallery and the State Museum of the East.

Abilkhan Kasteyev was born in 1904 in the village of Chizhin, Taldykurghan region, into a very poor shepherd family. His father died young and Abilkhan had to help his family. Initially, he worked as a shepherd for a local nobleman. Then, in 1926, he left his native village and moved to the city of Zharkent, where he became a laborer helping to build the Turksib railway, one of the main components of the first Five-Year Plan of the young Soviet state. Kasteyev quickly attracted attention by carving a grand bust of Lenin out of a rock, a feat that earned him the universal approval of his colleagues—and a newspaper write-up by the reporter Salamatov.

The young republic needed not only workers and collective farmers, but also those who could capture and celebrate their labor—a national creative class. Furthermore, it was important to Moscow to develop various forms of national art, including by freeing the formerly Islamic regions of the Soviet Union from the religious prohibition on realistic art. Accordingly, at the request of a Russian customs officer named Zveriak, who noticed Kasteyev’s talent, district chief Sultangazy Sauranbayev sent the 25-year-old Kasteyev to the city of Verny (Almaty) to further develop his artistic abilities.

From 1921 to 1931, Kasteyev studied at the famous studio of Nikolai Khlyudov, a Russian artist who had arrived in Verny in 1877 and established his own school of painting for aspiring artists. This studio played an important role in the professional training of the first Kazakh artists, as well as in the development of Central Asian Soviet painting more broadly.

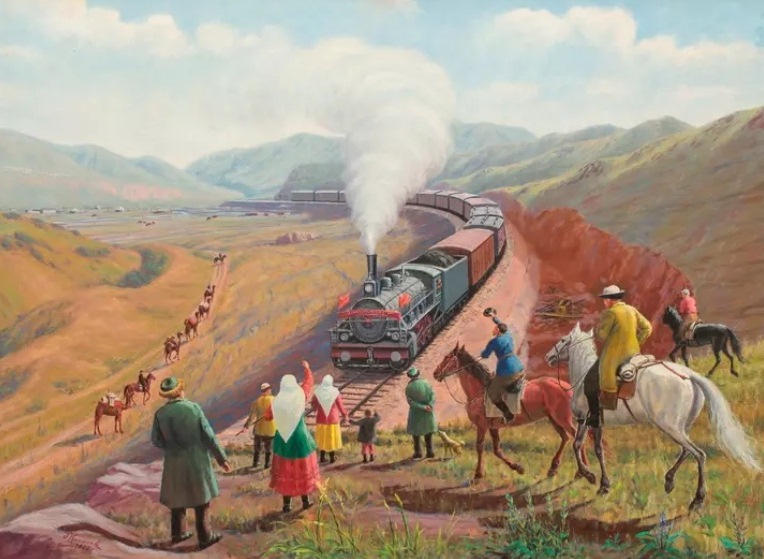

Another major influence on the young artist was his experience working on the Turksib (The Turkestan–Siberian Railway is a railway that connects Central Asia with Siberia. The bulk of construction work was undertaken between 1926 and 1931). The latter made a deep impression on Kasteyev and would become the impetus for the creation of his famous painting “Turksib,” (1969) which came to symbolize of the new era, as reflected in the iconic Soviet film “TIMES – FORWARD!” by M. Schweitzer.

In the center of the painting, we see the backs of Kazakh people—some on foot and some on horseback—in the foothills. We look through their eyes at the landscape below, along which runs a long iron train with red flags on the front wagon and a plume of steam coming from the high chimney. The nomadic people greet with the utmost joy this massive machine, which brings with it a world previously unknown to and unseen by the nomads: a world of science and technology, industry, and the development of cities and collective farms.

In 1934, Abilkhan Kasteyev participated in an all-republic competition held in Almaty for amateur artists to create a portrait of Abay and illustrations of his work. After winning a prize there, he went on to participate in the first exhibition of works by artists from Kazakhstan, which took place at the State Museum of the Peoples of the East in Moscow. From 1934 to 1936, Kasteyev lived in Moscow and attended the evening art studio named after N.K. Krupskaya, gradually mastering the Russian language, which in turn allowed him to learn the basics of artistic language.

Biographers report that the Kazakh diaspora came to his aid in terms of everyday life, helping him with accommodations in Moscow. He spent a lot of time at the Tretyakov Gallery, studying the works of classical masters. Kasteyev also became a regular participant in international, all-union, republican, and city exhibitions. In 1937, he was accepted into the Union of Artists of the USSR.

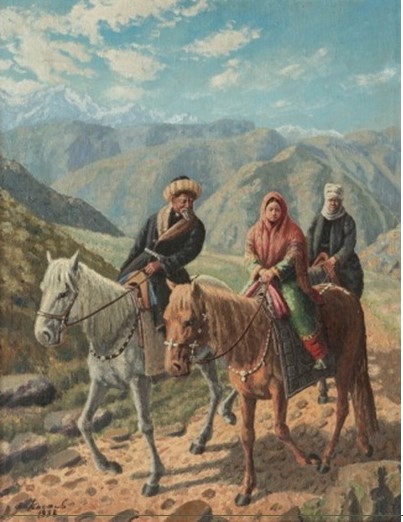

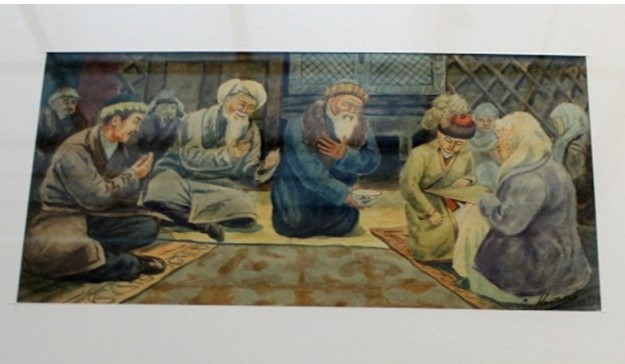

In the 1930s and 1940s, the artist worked on creating a large series of watercolors called “Old and New Way of Life,” in which he reflected on the “fading” past, demonstrating his skills not only in narrative painting, but also as a master of the psychological genre. In works such as “The Violent Abduction of a Girl” (1937), “The Bride’s Abduction” (1950), and “Matchmaking of the Bays,” Kasteyev depicts the negative and corrupt aspects of the “bygone past,” empathetically conveying the powerlessness of women and social inequality, which he himself experienced as a child while working as a laborer for a bay. At the same time, he lovingly and warmly portrays the life and traditions of his compassionate and generous people, who are depicted as living in harmony with nature in the vast steppe surrounded by mountains.

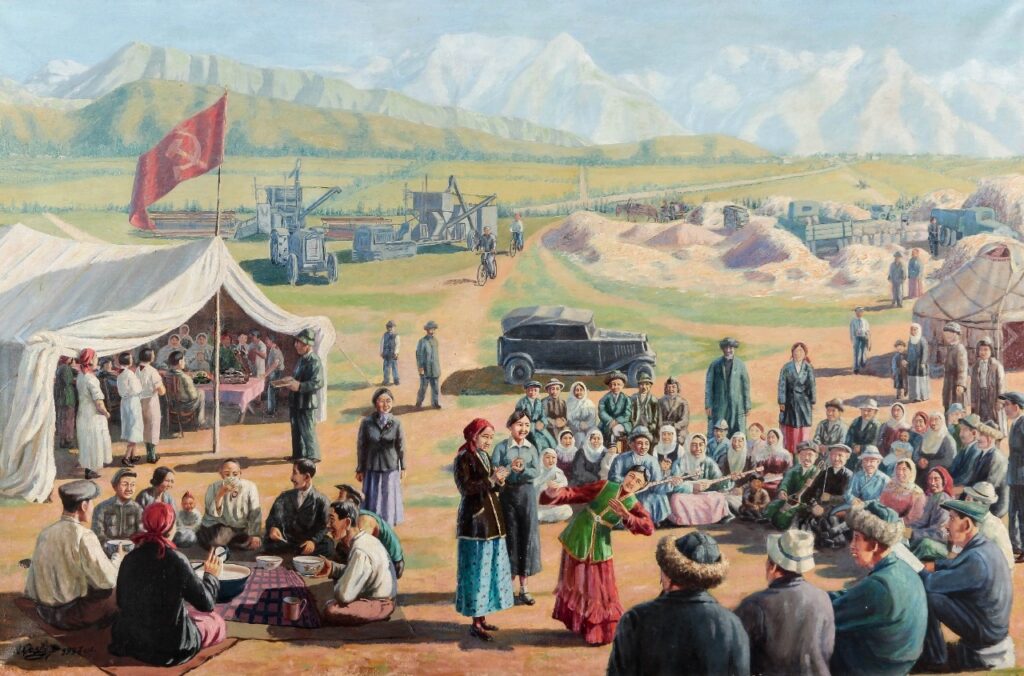

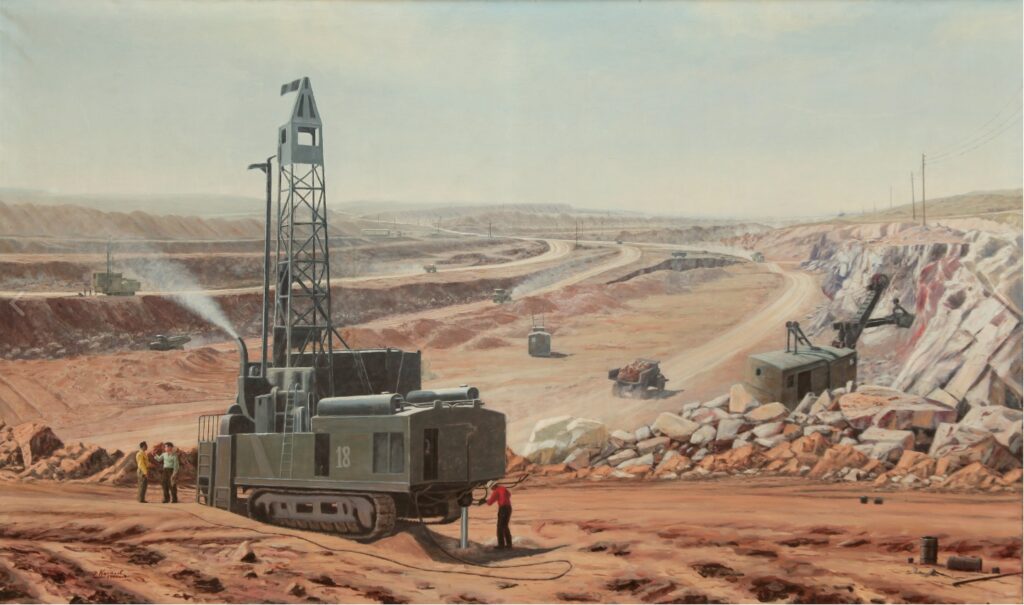

Like many representatives of the Soviet intelligentsia who enjoyed the direct support of the central authorities, Kasteyev sincerely rejoiced at and enthusiastically welcomed the Soviet modernization of his homeland: the first tractor and combine, the first train and airplane, all of which innovations became an integral part of his native steppe. Amir Jadaibayev, an author of Kasteyev’s biography, notes that the artist had a special love for depicting technology: “Turksib developed in Kasteyev a special reverence for technology. Industrialization was a crucial factor in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And later, Kasteyev meticulously depicted various technical means—tractors, trains, airplanes, machines, and other industrial equipment—in his industrial landscapes. Such was the trend of the time.”

The series of industrial landscapes belongs to the style of Socialist Realism.

Despite Kasteyev’s love of technological progress, this painting in particular already shows a dissonance between nature and technology. Here, the machines take on a formidable look as they fiercely tear apart the suffering land.

During the Great Patriotic War, Kasteyev was recruited to work at KazTAG, the main information agency of Soviet Kazakhstan. During this period, at the party’s request, he created posters and compositions on the themes of war and the labor of collective farmers in the rear. Soviet artists were actively involved in propaganda tasks determined by the government, which played a colossal role during this period. However, official work based on party tasks always carried risks for the artists. All artists had to go through special censorship—commissions that reviewed the works from sketches to their final implementation. Commission members often nitpicked and forced artists to redo their works.

In the post-war period, the Soviet government demanded even greater dedication, pathos, and monumentality from the creative intelligentsia. But the human dramas of that grim period could not help but affect the moods of the artists, who sought to convey the feelings of the individual in contrast to the universality and collectivism pursued by the avant-garde and Socialist Realism. In January 1936, Stalin highlighted the danger of “alien formalism in art.” On January 28, Pravda published an article titled “Confusion instead of Music,” directed against Dmitry Shostakovich’s works. Censorship in art gained strength. And Kasteyev, like some other artists, fell under this scythe. At one of the meetings of the Union of Artists, Kasteyev was accused of naturalism (a realistic direction in art that opposed the pathos of Soviet realism). Someone expressed the opinion that he inclined in this direction, perhaps because his technique and style of painting were characterized by meticulous attention to detail. But fortunately, there were those among his colleagues who came to his defense: “This is his artistic character. He writes and sees this way, he wants to convey the detailed reality of collective farms.”

This saved him from persecution. In 1942, Kasteyev’s first solo exhibition—featuring 143 works by the artist—took place in Alma-Ata.

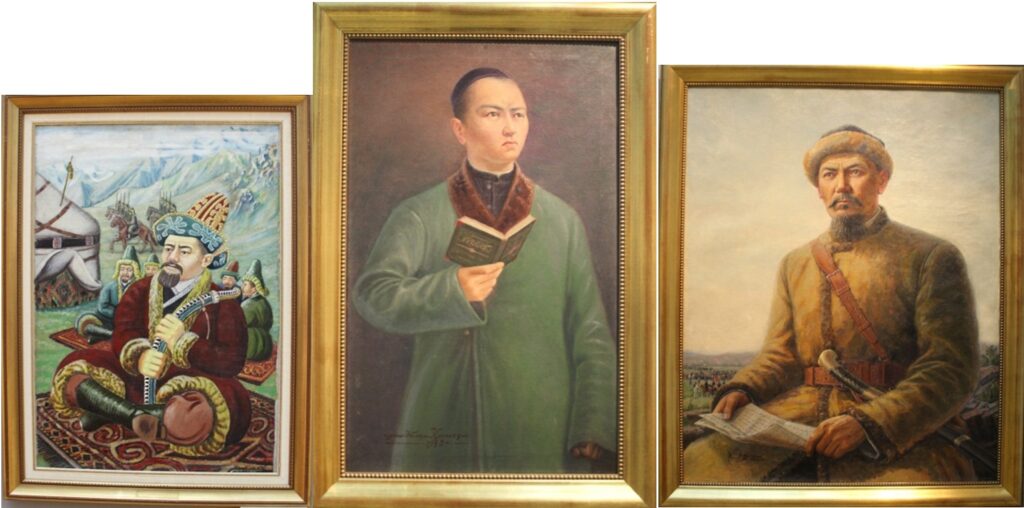

In 1944, Abilkhan Kasteyev was awarded the title of People’s Artist of the Kazakh SSR for recreating the image of Amangeldy Imanov (April 3, 1873—May 18, 1919), one of the leaders of the national liberation movement of 1916 against the colonial policies of the Russian Empire and a hero of the civil war of 1918-1920, who contributed substantially to the establishment of Soviet power in Kazakhstan.

The portrait was painstakingly recreated based on descriptions provided by Imanov’s relatives since there were no photographs or images of him available. For this purpose, the artist traveled to Turgay, the hero’s hometown.

Kasteyev’s opus includes several portraits of Amangeldy. Each of them conveys the nobility and dignity of the Red bata (Kazakh warrior). His courageous features express confidence in the righteousness of his choices. Amangeldy is presented as the Kazakh Robin Hood, a defender of his fellow impoverished countrymen and a legendary hero of the new ideological system.

Portrait painting occupies a special place in Kasteyev’s opus. He drew an array of iconic images that reflect the history of the Kazakh people and Soviet Kazakhstan, among them such celebrated names as Kenesary Khan, Jambul Jabayev, Chokan Valikhanov, Amangeldy Imanov, and Baurzhan Momysh-uly. He also produced portraits of ordinary workers: shepherds, milkmaids, drivers, front-line soldiers, and harvesters.

According to his youngest daughter, the Soviet authorities did not allow Kasteyev to leave the Soviet Union because of his portrait of Kenesary Khan, a charismatic leader in Kazakh history who challenged Russian colonization and longed for his people’s true freedom.

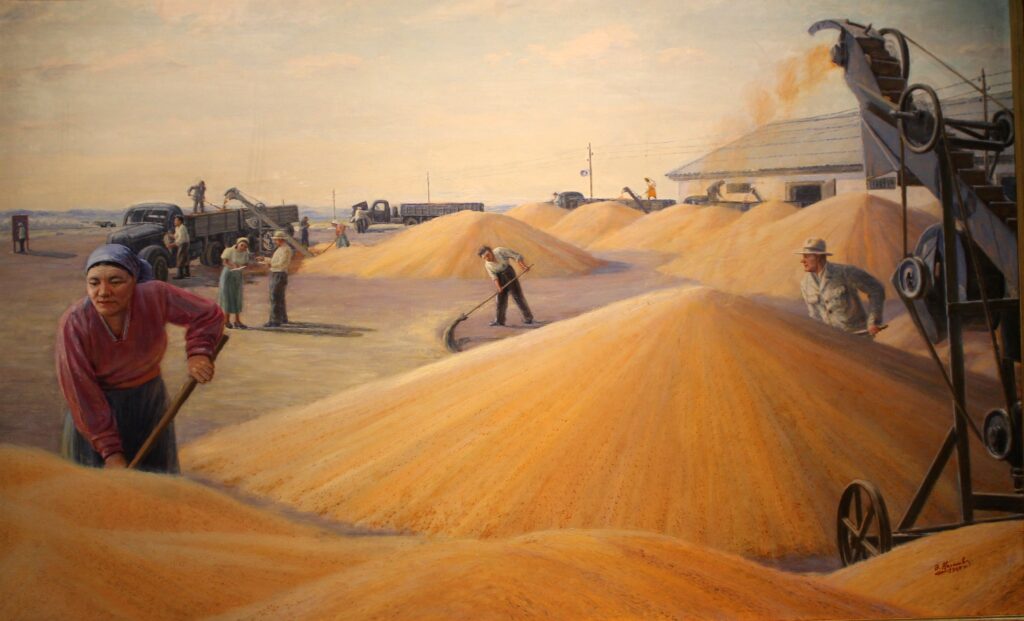

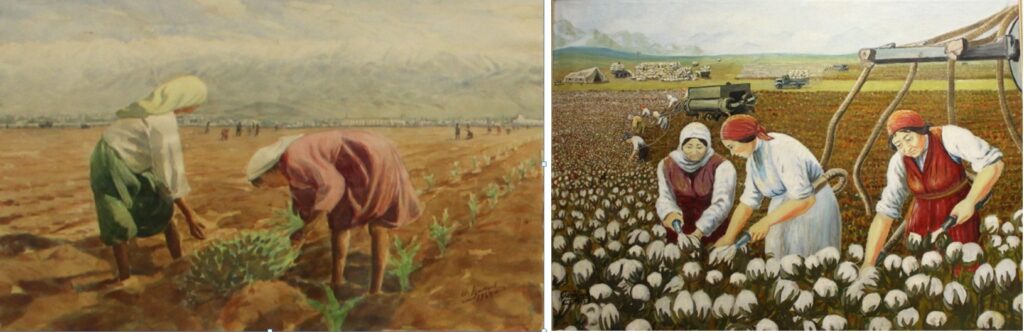

The theme of labor as one of the basic values and responsibilities of members of a socialist society is central to many of Kasteyev’s works.

Kasteyev’s compositions dedicated to the labor of rural workers surpass the product of the ideological line of the Communist Party. Indeed, they are reminiscent of the masterpieces of great masters of world art such as Bruegel and Van Gogh, who portrayed the great tillers of the land in their works. They convey a great respect for the creative labor of their fellow countrymen and compatriots. He achieves perfection in capturing the humility of their characters, which are devoid of any special personal traits.

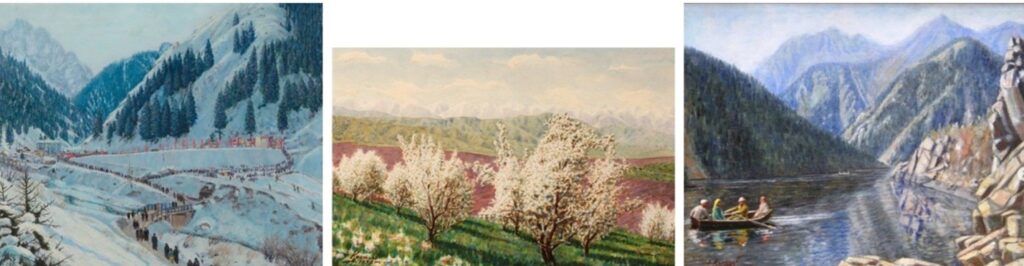

Kasteyev’s favorite genre was the landscapes of his native Kazakhstan. Works in this category include the airy and spacious “View from the Sovnarkom House to Medeo,” the calming pastoral canvas “Milking the Mares,” and the spring landscape “Blooming Apple Trees,” painted in 1956, which depicts Alma-Ata as floating in pink haze, in the awakening rhythm of nature, with the trees like brides dressed in white attire. It also includes the crystal transparency of the mountain landscape “Lake Issyk” and the vast widescreen painting “Talas Valley.”

All these works demonstrate the artist’s reverence toward nature, the breadth of his soul, the scale of his gaze, and the optical perspective of a born steppe-dweller. He anticipated the emergence of widescreen cameras. To satisfy his unquenchable thirst for travel, he embarked on plein-air trips throughout his homeland, where he was always warmly welcomed by local villagers and district administrations, but even these warm receptions never distracted him from painting. Everyone knew that Abilkhan would not approach the set table until he finished his study.

In the mid-1950s, Kasteyev was the chairman of the Union of Artists of the Kazakh SSR and was elected as a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Republic. The artist was awarded the Orders of Honor, the October Revolution, and the Labor Red Banner. Behind these brief phrases are the years that Kasteyev dedicated to public work. Despite his celebrated status, he continued to help the youth and his colleagues in the art community. He always, while juggling his responsibilities, made sure to provide those in need with housing, childcare, or scholarships for education. The artist himself lived in very modest conditions despite his accolades and large family, consisting of his devoted wife, Sakysh, and nine children. It was only with the help of the famous American artist Rockwell Kent that he was able to partially realize his dream of having his own home, which has now become the Abilkhan Kasteyev Museum.

In the State Museum of Art named after Kasteyev, an exhibition dedicated to the 120th anniversary of the founder of Kazakhstani painting opened in January 2024, showcasing the creative legacy of Abilkhan Kasteyev, truly a people’s artist of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. It presents the history that he captured on his monumental canvases and provides more information about the first artist of Kazakhstan—who rose from the ranks of thousands of unrecognized steppe artists who did not leave their works for future generations to admire and draw inspiration from.