Since at least the time of Marco Polo, the Kazakh steppes have attracted many visitors from the West: travelers, diplomats, traders, and researchers. Their notes, books, and memoirs provide invaluable insight into the various epochs of Kazakh culture and history. But with the advent of photography in the nineteenth century, travelers’ notes become even more captivating: the black-and-white images grant us access to Kazakhs’ personal lives, families, and communities.

This article presents and discusses the unique and mostly unknown photos taken by one French traveler in the Kazakh steppes.

Paul Labbe (1867-1943) visited the region at the turn of the twentieth century. A linguist, anthropologist, ethnographer, and member of the French Geographical Society, he was one of the best French experts on the peoples of Siberia, Central Asia, and the Far East. He had learned Russian at the School of Oriental Languages and studied Russian ethnography and religious beliefs of other Russian ethnic minorities. Over many years, Labbe visited most of the Russian Empire: Siberia, Kazakhstan, Sakhalin, Mongolia, and Manchuria. He wrote a total of five books after these trips, describing the lifestyle, customs, and traditions of the peoples who lived in the Russian Empire in that period. His writing is very accurate, with a little irony for added sparkle.

In his book On the Roads of Russia, from the Volga to the Urals1 (published in 1905 but translated into Russian for the first time only in 2017), Labbe documents his trip to the Volga, Southern Urals, and other regions of today’s Russia and Kazakhstan in the summer of 1898. This journey began in June 1898 from Yaroslavl and Kostroma: Labbe traveled along the Volga to Astrakhan, then by ship to Kazan, and then on to Ufa. Along the way, he spoke to the inhabitants of the cities along the Volga, Bashkirs and Zhayk Cossacks. His writings are easy to read: Labbe interpolates conversations with local residents to explain their customs to the reader. Moreover, whereas he summarizes dry facts and statistics only very briefly, he clearly emphasizes visual documentation: His black-and-white photos reveal an artistic person with a great sense of perspective and sharp vision. All in all, the work is an indispensable text for historians and researchers of the Central Asian steppe.

The following selection of images from Labbe’s journey2 shows diverse people and places in the Kazakh provinces of the Russian Empire and yet creates a common portrait of the steppe of that time.

First of all, Labbe’s text features many photos of migrating households traveling in close-knit communities, with men, women, and children united in daily routines. This was a time when many Russian settlers were arriving in the Kazakh steppes and Kazakh nomads themselves were moving more frequently in search of dwindling resources.

In this picture, we see migrating Kazakh families caught on camera in the midst of moving across the Semey region. (Picture 1). Men with unsmiling faces regard the camera suspiciously; women sport impeccably white headwear; and small, barefoot children try to tie their yurts and wooden equipment needed for the long journey onto camels.

The next picture shows several Kazakhs traveling on the Irtysh River in the company of several Russian officers and even an Orthodox priest. They stand close together on a wooden ferry, packed in with an expensive-looking carriage and a few horses. The Kazakhs, who can be distinguished by their round caps, were probably in the formal Russian service (Picture 2).

The next photo imparts the air of a summer steppe. In the deep grass, we see a few lightly dressed adult Kazakhs with calm faces and curious children surrounding three beautiful white horses. (Picture 3).

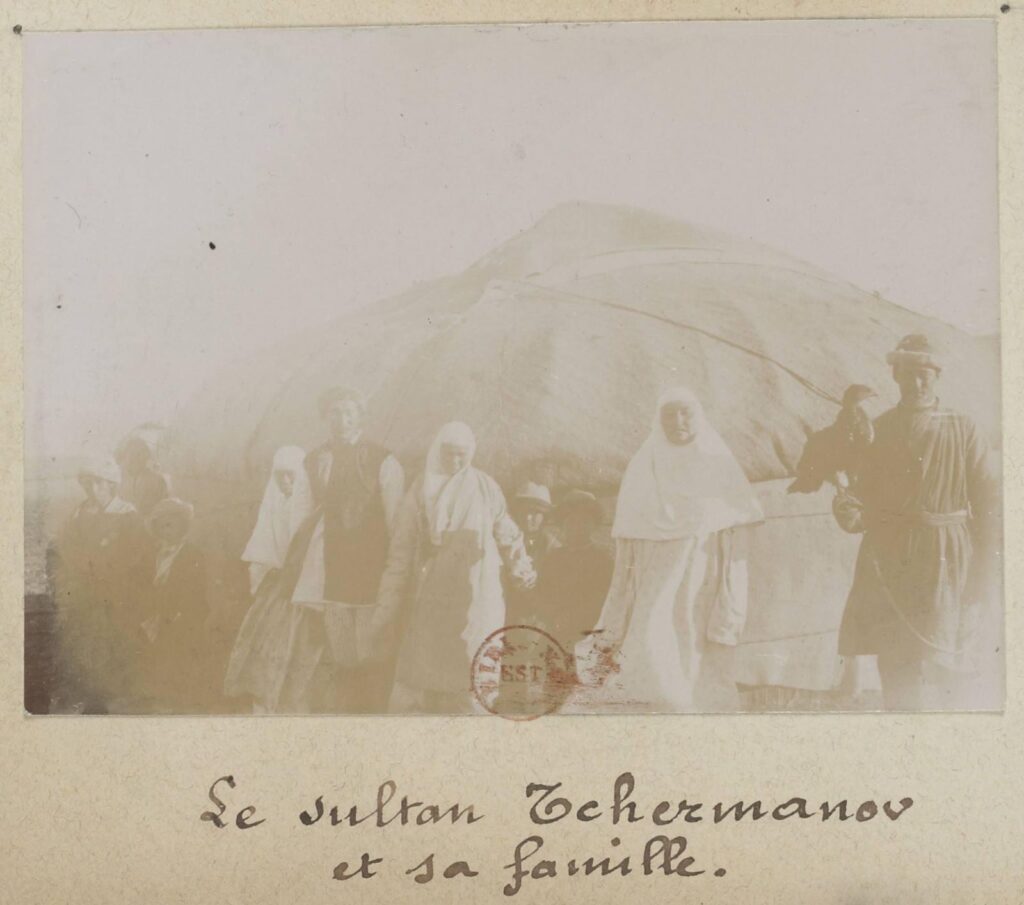

Labbe captioned a group photo taken in front of a yurt “sultan Shermanov and his family.” Sultan and his brother, who is holding an eagle in his hand, are pictured among neatly dressed women in white turbans. (Picture 4). Women with open and confident faces stand proudly alongside the men, with no visible gender hierarchy.

The next photo shows sultan’s young nephews. Kazakh children in formal dress and round caps in the Western fashion, they stand on what looks like a small tarantass. They may seem a bit privileged but also look serious and independent for their young age. (Picture 5).

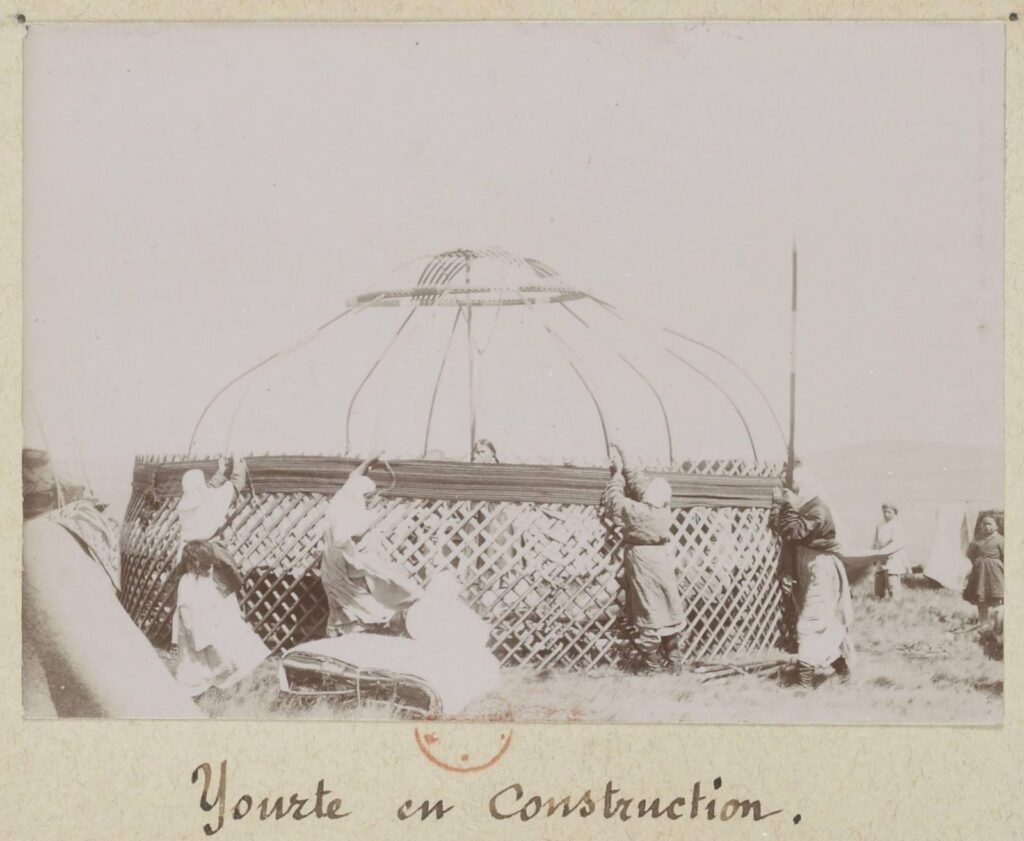

The next photo, captioned “The construction of a yurt,” shows Kazakh women whose white dresses flutter in the wind as they set up a tall yurt. The women appear to do this work with pleasure and at ease, as if dancing around the towering structure. (Picture 6).

The image of village children holding books in their hands is really compelling. Boys and girls of different ages and probably social standing show their zeal for knowledge and literacy (Picture 7).

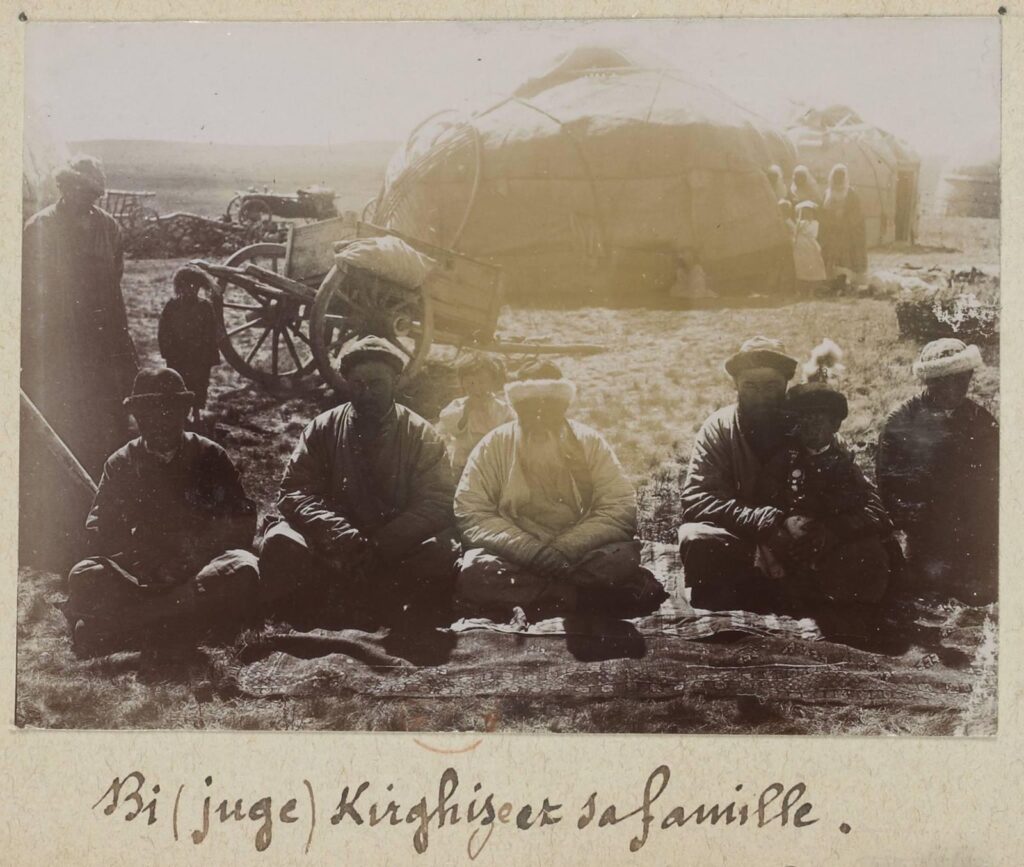

The next picture offers a glimpse of religiosity in the lives of Kazakhs. A benevolent-looking mullah sits on the carefully laden blanket on top of the carpet in front of the yurt with men (apparently a bi who was a judge) and young boys. In contrast to the earlier picture, women and girls stand back and watch from a respectful distance (Picture 8).

In a photo that Labbe titled “Saba,” village life is depicted in its raw form. We see the rich Kazakh pastures in grand perspective; indeed, one can almost smell the meadow. (Picture 9). Labbe may had captured the villagers on the road as they were transporting a cart full of straw.

In a photo titled “sultan Akbay and Judge,” two people stare at the camera from amid an endless sea of grass. (Picture 10). A bearded man with a medal (probably a judge’s medallion) on his neck and a black cap on his head has an official look, while his companion—dressed in a white suit with a richly decorated hat—looks aristocratic and sultan-like. The image thus juxtaposes the unique combination of judicial and executive powers at work in the nineteenth-century steppe. The judicial system in the steppe, established by Genghis Khan himself, was very efficient and able to deal with conflicts in all their variety.

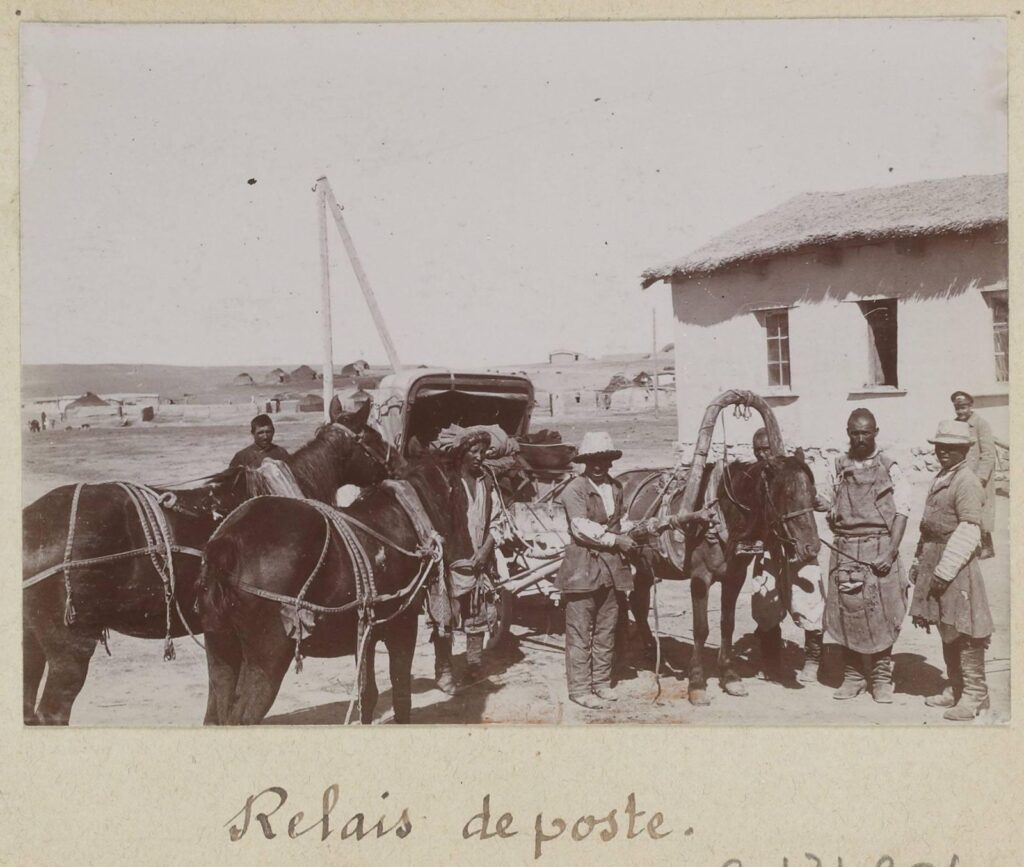

Another shot shows a simple post office. The men who surround the postal carriage look worn out and have tanned and dusty faces, probably the result of taking post across vast territories. (Picture 11).

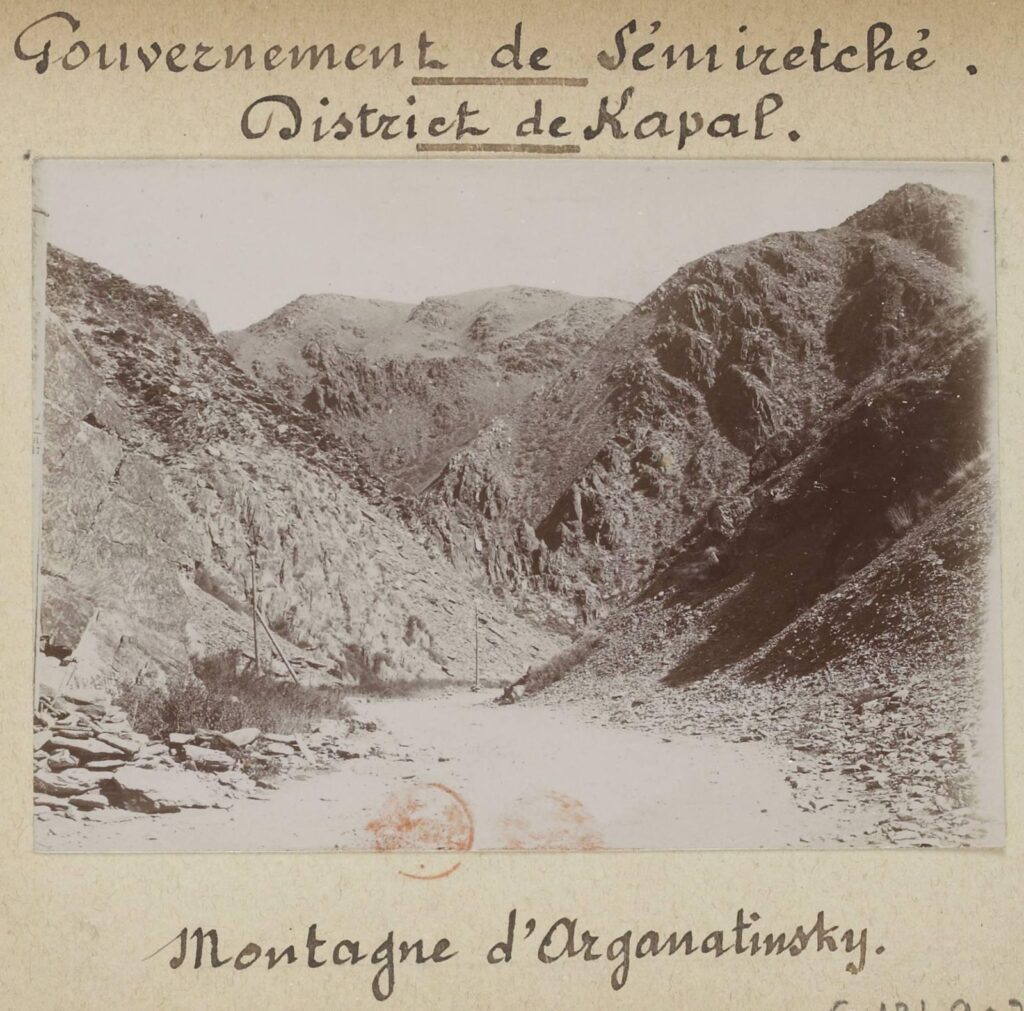

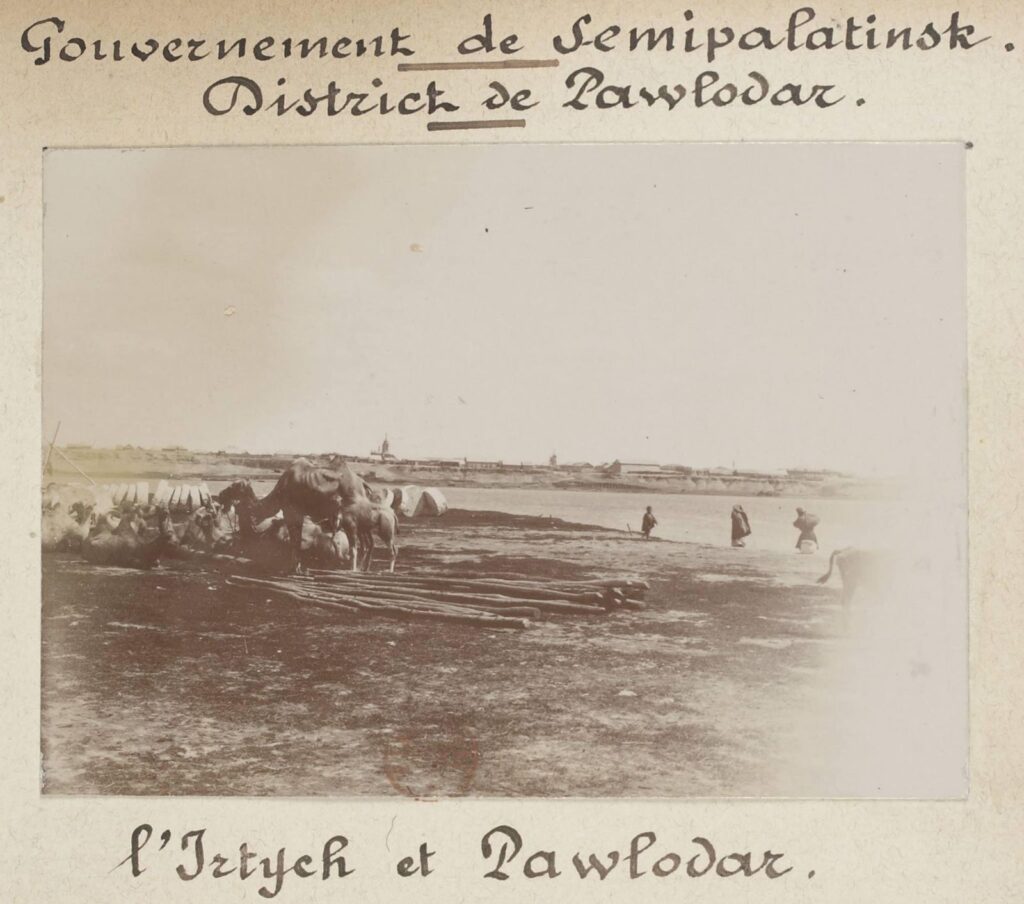

Two following pictures show various landscapes of Kazakhstan: the mountains of Semirechie and the great river Irtysh (Picture 12 and 13).

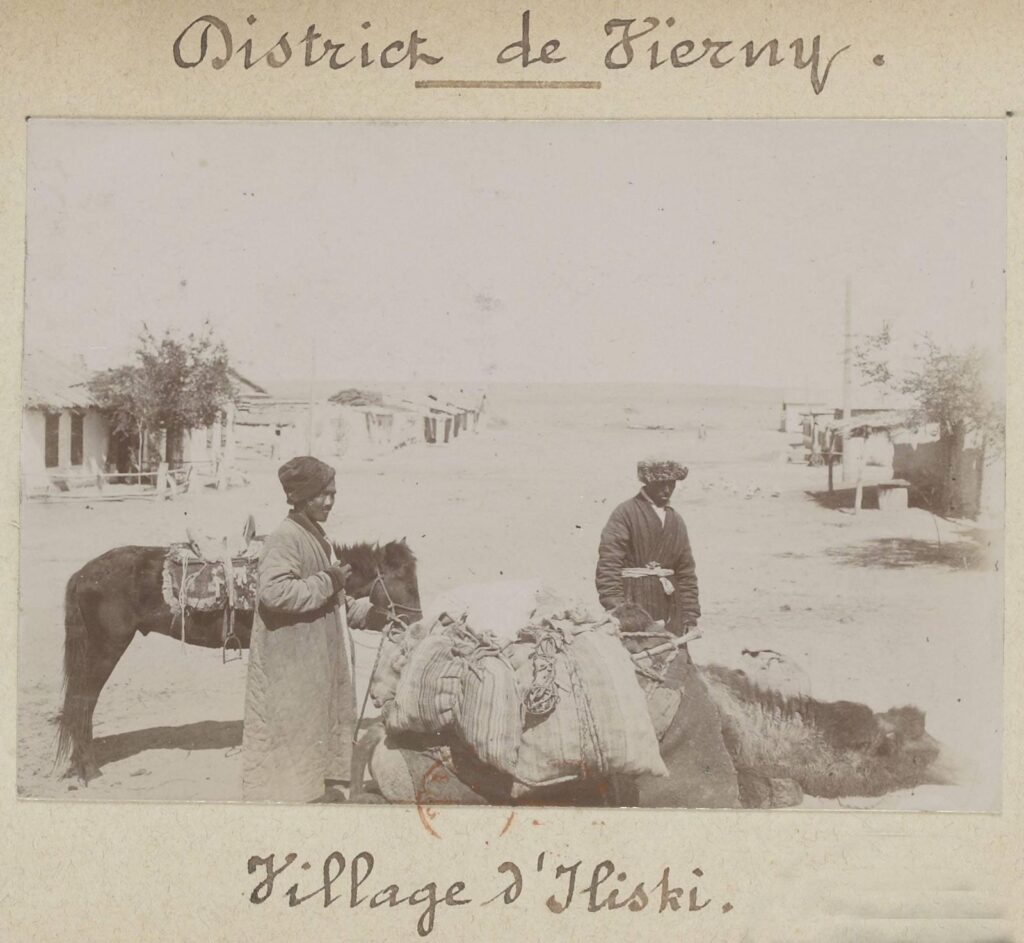

Picture 14 shows us the precursor of the present-day megapolis of Almaty. In Labbe’s day, this was Verny District. The picture, which shows spare houses surrounded by bushes somehow foresees the spirit of Almaty, with its colonial architecture and thick trees.

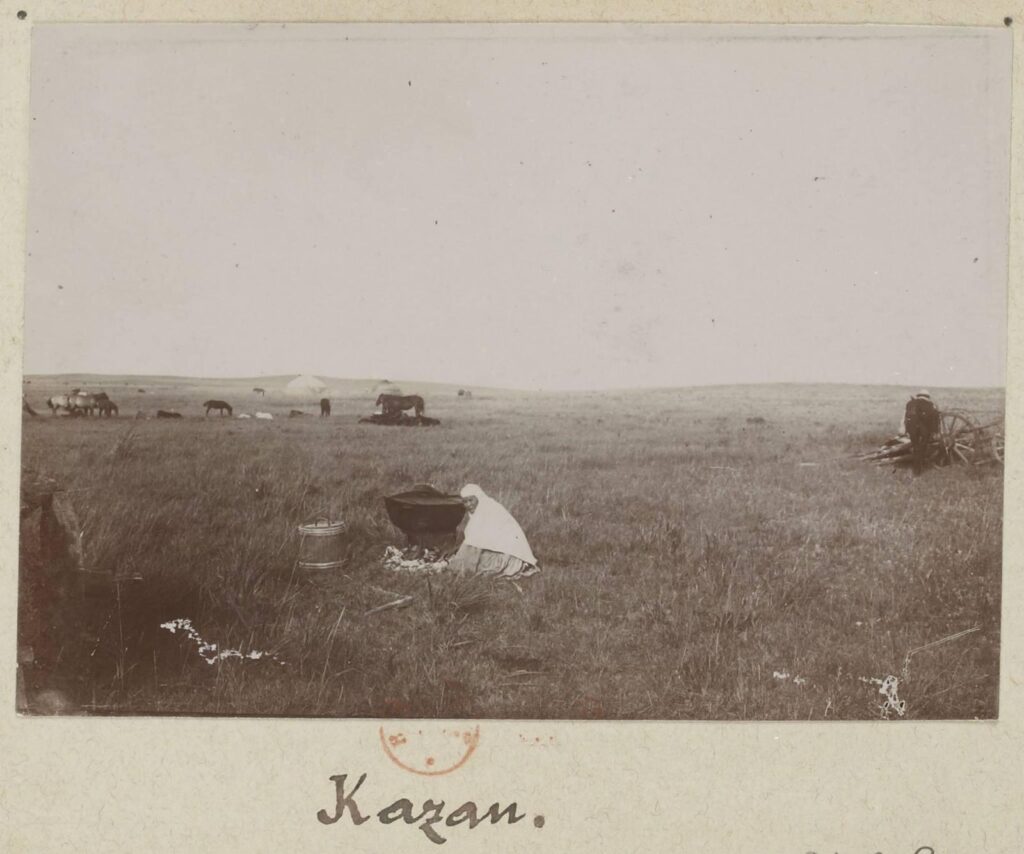

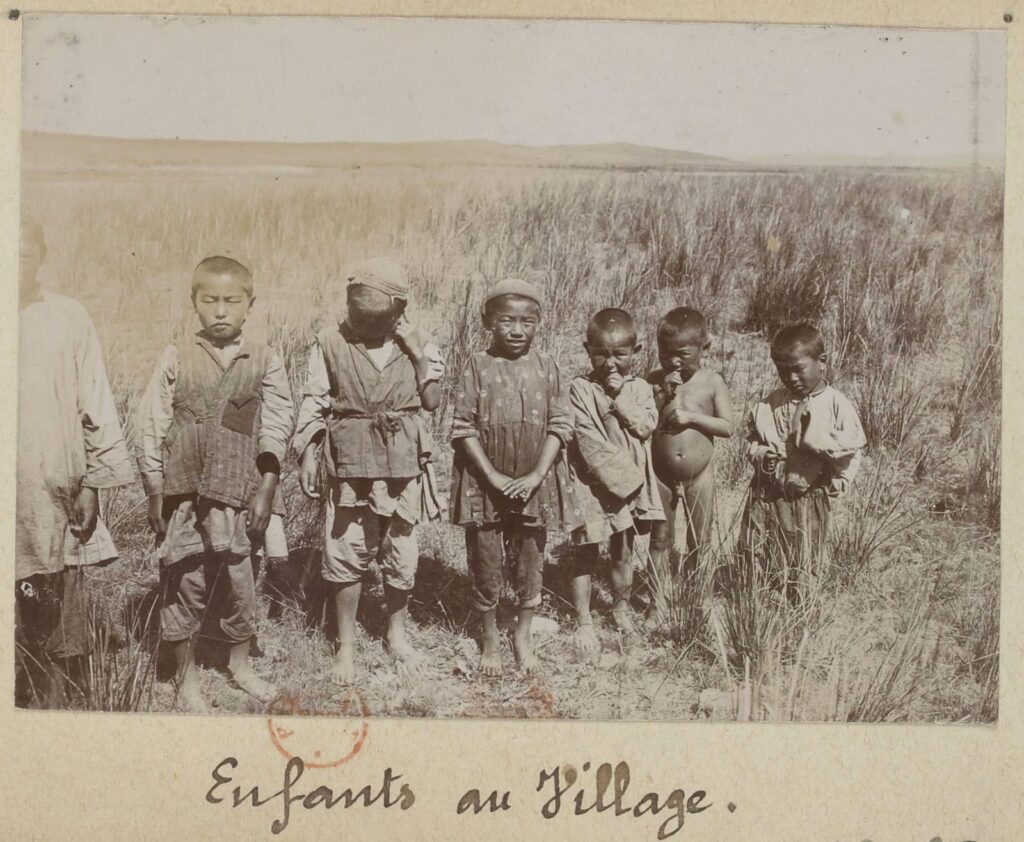

Let us conclude with the two pictures that add the most to Labbe’s portrait of family life in the Kazakh steppes. One captures a Kazakh woman, in typical crisp white headwear, sitting in the deep grass near a kazan (pot) to prepare food in the open air. As with all Labbe’s pictures, we can almost smell the pleasant aroma of wood burning and food cooking. The woman seems busy and lonely, but the background of the image reveals scattered horses and probably her family members tending to their chores at a distance. The other picture, this one of village kids, is particularly touching: their young faces in the burning sun show hope and joy, oblivious as they are to the upcoming torrent of tumultuous times that will change the Kazakh steppes forever.

Labbe’s work, which reached the Western readers of his day before quickly being archived in Paris museums, was very informative for those who studied the Russian Empire. The album might had been seen as somewhat exotic: to their eyes, the images might have appeared to show only endless faces amid grass and animals. Looking at these amazing documents over a century later, however, we can see much more: caring families, proud people, a breaking order, and a disappearing era.

About the author

Duisenali Alimakyn is a poet, journalist, and member of the Writers’ Union of Kazakhstan. He previously worked for the newspapers “Kazakh Literature” and “Egemen Kazakhstan.” He is now a fellow at the Abai Center in the USA.