Author

Alan Georgievich Medoev (1934-1980)

Alan Medoev was born in Leningrad in 1934. In the 1960-1980s he guided archaeological teams and expeditions in the field; he discovered and explored the significant Paleolithic monuments of the world: Semizbugu, Turanga, Khantau, Genghis, etc. in Central Kazakhstan; Shahbagata and Kumakape in West Kazakhstan; and Kudaikol and Karasor in Eastern Kazakhstan. At the same time, he began to study primitive art (petroglyphs, sculptures) along with Kazakh fine art, architecture, and the problems of Kazakhstan’s nomadic civilizations.

The drawings of A. Gorbatyi, taken from the book “Engravings on the Rocks” by Alan Medoev, were used in this article. This article is published with the permission of Viya Muragina (granddaughter of A. G. Medoev).

Rock engravings are among the most meaningful and widespread pieces of Kazakhstan’s visual art. Chronologically, they make up a huge time range: from the late Paleolithic era to the early 20th century A.D.

The most ancient pieces of work from the Paleolithic era are the remarkable images of fossil animals. This art ended after the disappearance of the wooly rhinoceros at the end of the Ice Age, followed by the disappearance of primeval buffaloes and aurochs (called “Tur“) at the beginning of geological modernity.

A remarkable late Paleolithic lithic art, called “sayak,” has been found in Sary-Arka (Central Kazakhstan).

The stone art moved to the next stage during the Neolithic age, with more developed cultures of desert steppes. Despite severe environmental conditions, the steppes and deserts of Kazakhstan were widely and densely populated by tribes of hunter-gatherers at this time. This era is remarkable because of the numerous sites of Neolithic age humans that have been discovered, along with their perfection of hunting weapons at the time and tools for processing bones, horns, and fells, all showcasing the nomadic lifestyle of the tribes.

There are not only images of animalism (common for the petroglyphs of the Neolithic age), but also images of people—mainly of the holy marriage alliance.

A number of battle scenes show that the life of hunter-gatherers was visibly complicated by intertribal clashes.

Some of them appear to be devoted to ritual competitions between two dueling halves of the tribe, where every social group differs by the type of its weapons and the warders of its leaders. The cult of the bear can be seen in the Neolithic petroglyphs as well. This figure, seemingly strange for the steppe civilizations, takes shape in a mobile sculpture made of stone. There is a statue of a standing bear carved in diabase (its height is about 18 cm.) found in the Kara-Ungur site (Northern Pribalhashye).

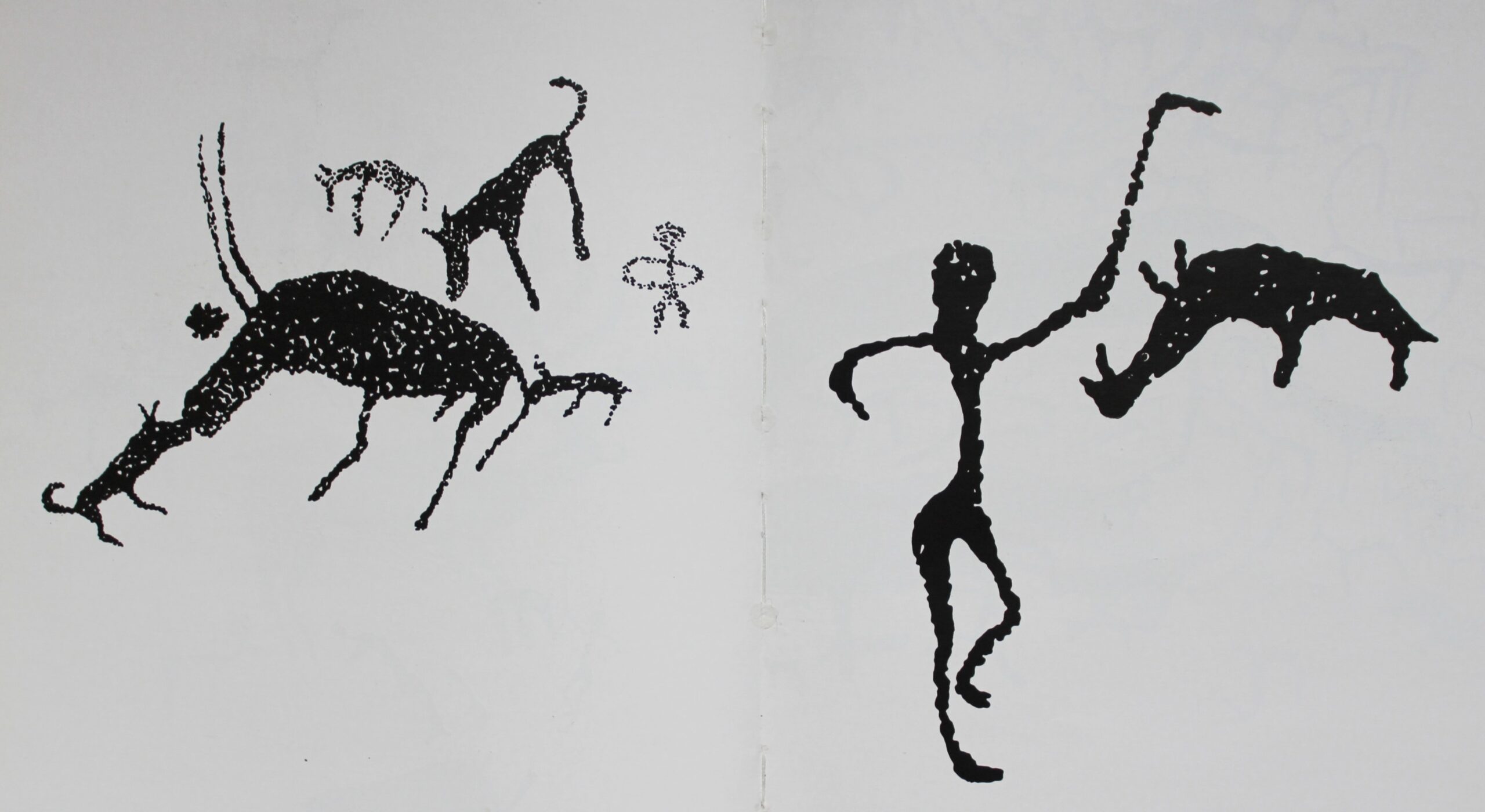

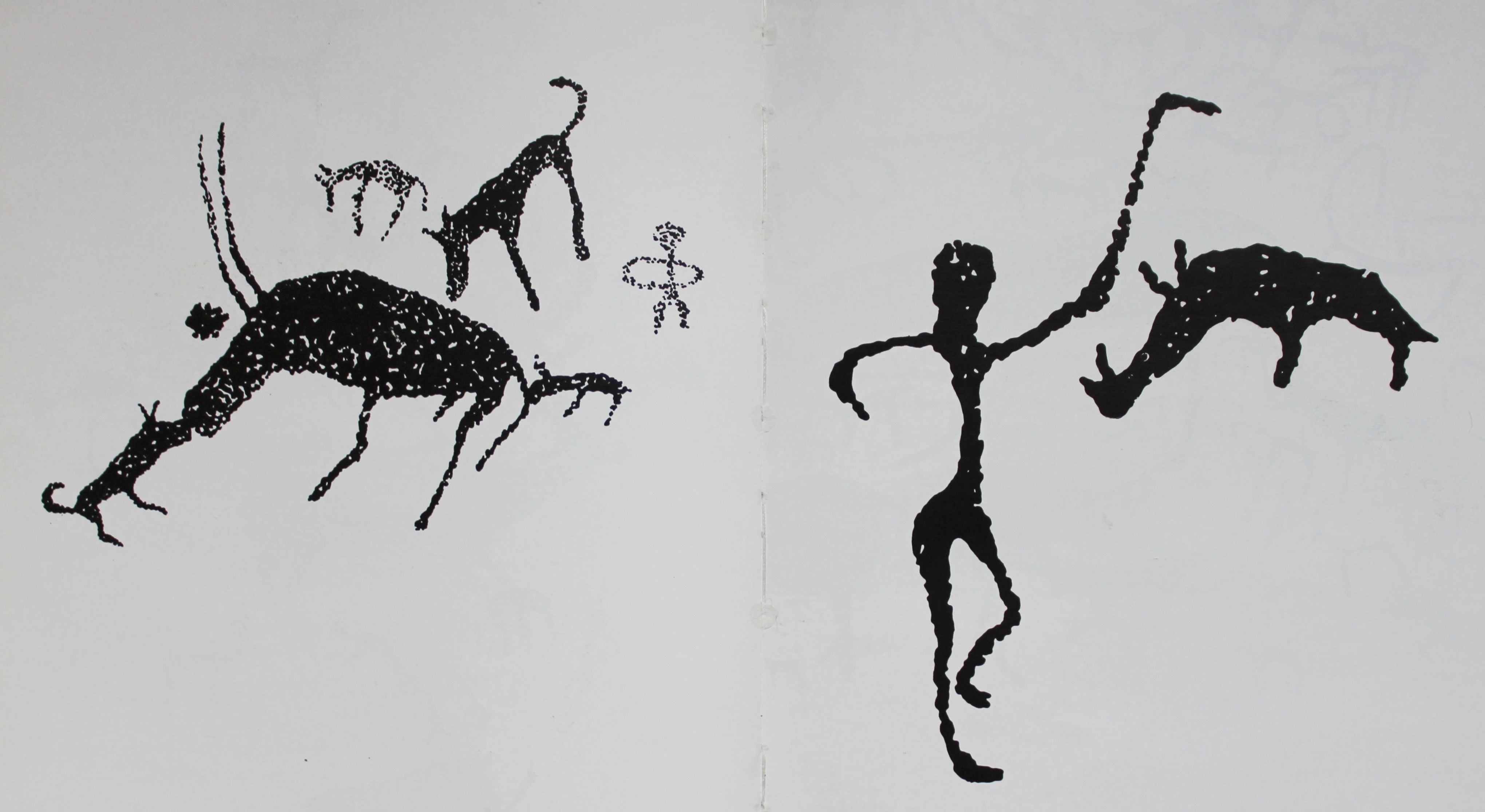

One of the carvings contains the image of a bear standing on his hind legs, or a man wearing a bear mask, and a horse standing in front of him. There is an anthropomorphic image between them presented in a clear mediation function. The semantic meaning of the picture is a request for protection from the Animal God—the bear, the owner of horses and animals, is also representing an embodiment of the image of the God of Thunder’s enemy. These traces, such as this cult of the bear discovered in Central Kazakhstan, bring a new and unexpected aspect to the study of Neolithic Eurasia. A lot of attention is given to the ancient Eurasian myth about the cosmic drama, which is personified in the image of a horned beast haunted by wolves or dogs (fig. to the left below).

A woman in Neolithic art is mainly presented as a priestess. For example, the magical effect and the power of a woman over beasts is shown in the below scene with a wild boar (Ulkentaldysai, Hantau mountains).

A graceful, slim, naked woman with her hand up is holding a warder with which she is blessing a beast. Another composition depicting an act of coition in which a woman is blessing a man with a similar warder (found in Terektysay, the Khantau mountains) is extremely important for the reconstruction of women’s archaic social status in society at the time. Further evidence of this is clear from similar depictions that arrange a woman to the left side and a wild boar and man to the right side. Images associating a woman (a clay relief) and a wild boar (often represented by one of its features: a chap, a head, etc.) are specific to the temples of Chatal-Guyuk (Southern Anatolia, between the 6th and 5th millennia BC).

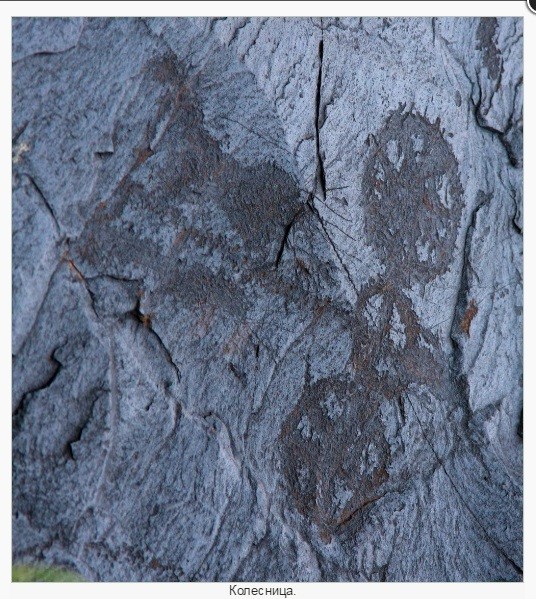

There are two main traditions in the petroglyphs of the Bronze age. The first one is the autochthonous, dating back to the Neolithic culture of Sary-Arka. The second one belongs to the second half of the 2nd century BC. It was brought by the tribes of war wagons.

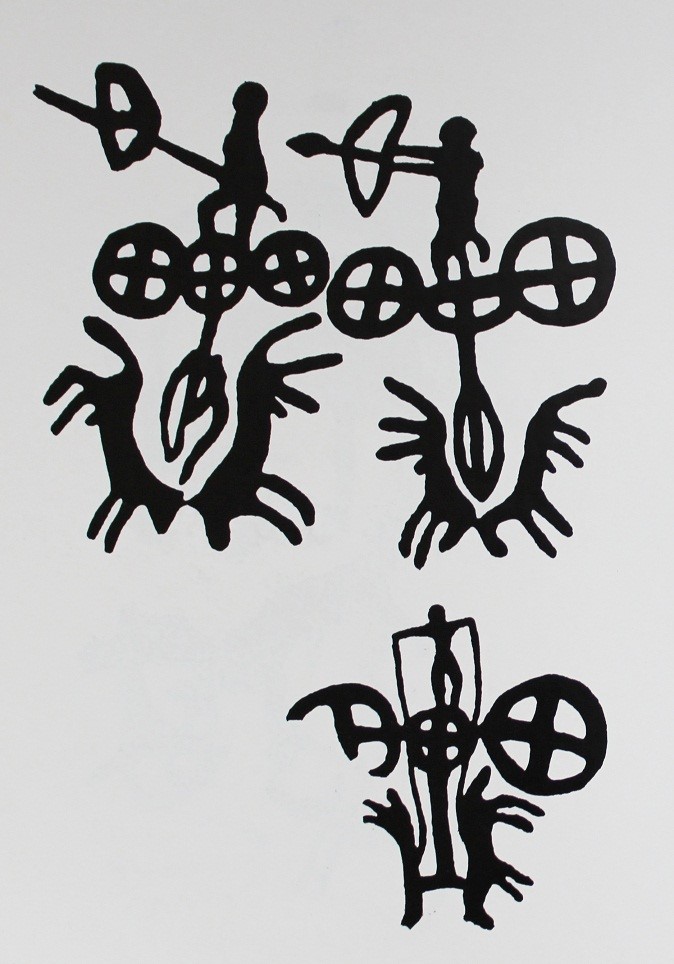

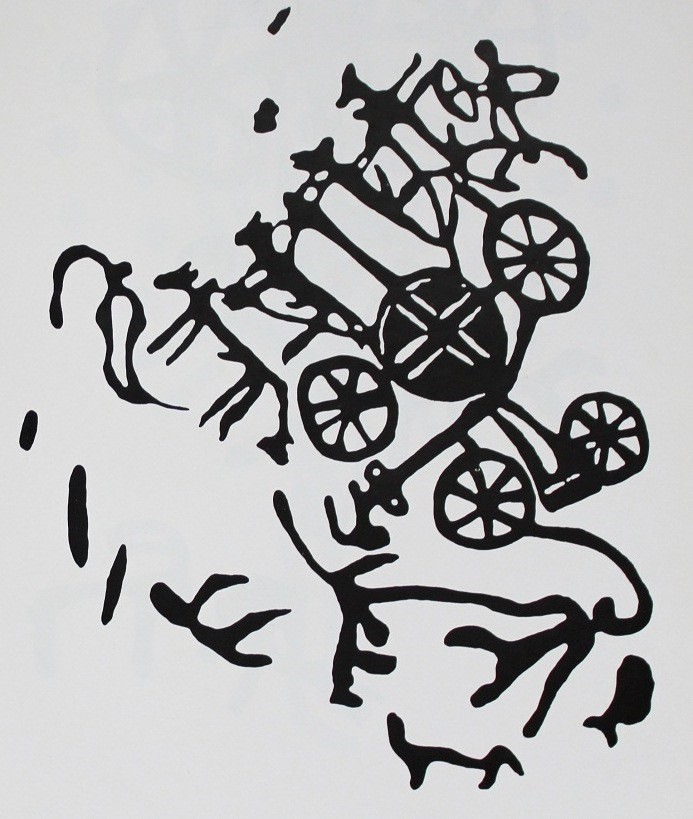

The material culture of these tribes has not yet been archaeologically established in Kazakhstan, but by using images inscribed on rocks, their path can be traced through a number of holy places built in the canyons of the Chu-Ili mountains. It was an army on wagons, which was steadily moving from the north or northwest to the south, with a great deal of cattle, mostly represented by half-wild bulls. The Solar Mythology based on the concept of humans as “Children of the Sun” was developed between the war wagon tribes.

The war chariots of Sun-faced gods and threatening bulls, the images of the Solar Divine, were often created by the artists of these tribes and engraved on rocks. It was a short episode in the ancient history of Kazakhstan, but its meaning moves beyond the area in which the migration took place.

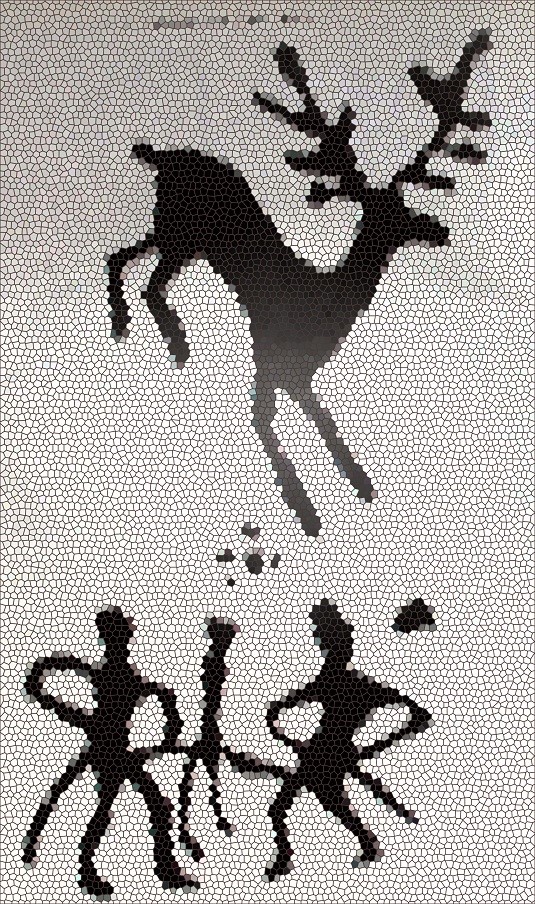

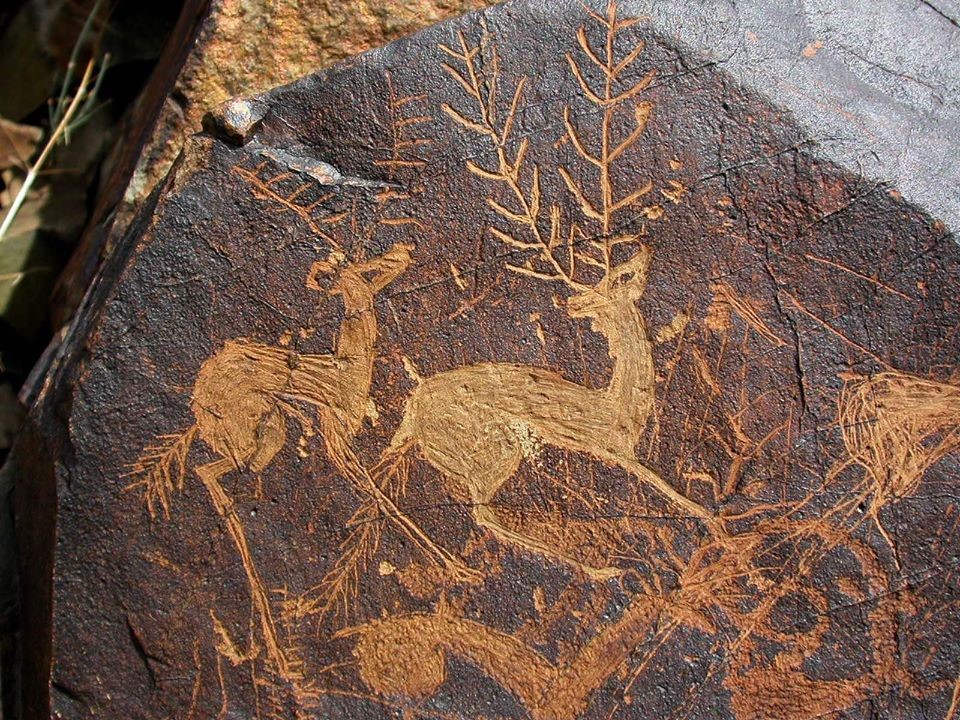

The petroglyphic tradition of the war wagon tribes is clearly connected with the Proto-Indo-European ethnocultural community. Was there a Proto-Turkic substrate in the Neolithic age of Kazakhstan? The archaeological evidence of this is most likely seen in the microlitic culture of Sary-Arka, which greatly differs from the Mesolithic and Neolithic cultures of the Middle East and the Southern Urals. The rock art of the ancient Turks (6th-8th centuries) is strikingly different from the art of the Sakas, but is similar to the Neolithic art of Sary-Arka. The Scythian style of animal art, which is vividly demonstrated here, stands out amidst the art of the Neolithic tribe and of the ancient Turks. A stag is presented as the main character of early nomadic petroglyphs, as in the mobile art of the Sakas (the Scythians).

The images of other animals (a roe deer, a Persian gazelle, a hunting leopard, etc.) are a regional feature.

One outstanding work of the early nomads of Sary-Arka is a composition of a scene in which a deer is driving forward with the main participant, a naked woman going down to her right knee and drawing a bow. The arrow is aimed at the deer, driven onward by horsemen in a stall built of stakes and bended wood strips. The bow in the hands of the Amazon was designed with precision: it is a product of the transition from the three-type to the five-type, which, together with the mannerisms and elements found in the figures of the deer, allows us to date this unique composition to the Common Era (CE).

The engraving of an Amazon, discovered in the Hantau mountains in 1965, caused a sensation among professionals in the field of Scythian archaeology. It was the first iconic document of the Eurasian steppes that provided confirmation of the ancient tradition of women-warriors among the early nomads. A few years later, a gold decoration of the horse’s headstall with an image of a horsewoman striking a deer with an arrow was found in one of the Scythian mounds in Ukraine (near the village of Gunovka).

A mythological plot common to the Scythians involves an Amazon hunting a deer, and the deer’s death because of the Amazon’s arrow.

Another outstanding piece of the early nomads’ art represents the battle of two warriors on foot. The above scene’s heroic and epic character is unmistakable. But the most interesting thing is that there is a woman representing a judge in the scene. She holds the same position as a judge in the era’s spear duels. There is an image of a wild goat (Tau-teke) above the heads of the participants. A horned animal represented as the Supreme Being, whether in the form of a deer or a maral, is frequently found in the art of the nomads. For example, the complex symbolism on the headdress of a Saka warrior (found in the Issyk mound) is crowned by a miniature figure of a golden Marco Polo’s sheep. This tradition can be traced back to the Bronze age in Kazakhstan. One of the compositions found in the mountains of Khantau contains an image of the sacred marriage action happening under the figure of a huge maral.

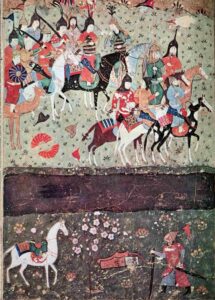

The creative genius of the horse nomads found its expression in the rock art of the ancient Turks (6th 8th centuries.). Their heroic era is characterized by the image of a standard bearer on a horse and armored knights on armored horses (cataphracts).

These characters are found on the rocks of Eastern Siberia, as well as the Mongolian Altai. Here we may also see more secular aspects of the culture, including proclamations or diplomatic documents, for instance. In this regard, this composition in the Kendyktas mountains (Southern Kazakhstan) is more prominent. The picture has no analogues in the petroglyphs of Asia.

It contains an image of negotiations between 3 ancient Turks, with 3 representatives of some unknown tribe. Two Turks are in the saddle, and one Turk is dismounted from the horse. They hold flags and have other items which clearly indicate their social and political affiliation. They have bashlyks, or pointed hats, and boot flare horse riding pants. Their horses’ manes are depicted as three-pronged, and there are plum holders and horse brasses which were used as amulets, often referred to as Kutas or Nauz in professional literature. The color cloth is made in a shape resembling the head of a wolf with an open mouth. This peculiarity supports the information gained from ancient Chinese sources regarding the wolf flag of the Kagan of the ancient Turks. Characters not possessing a horse are standing in a line in front of the horsemen. They have their own flag with a square cloth that contains an image of a limb (a solar sign) in the center. Additionally, one representative of the unknown tribe has dismounted from the horse and is shown down on one of his knees, while two of his assistants stand with their right hands up. This may indicate their assurance of loyalty or obedience to the Turks.

The petroglyphs of the Oghuz-Kipchak and Adaevsky traditions (the Mangyshlak) complete the path of the rock art in Kazakhstan, which extends back at least twelve or fifteen thousand years. This art shows that the late petroglyphs were not of simple content or a low aesthetic level, which is commonly accepted in the archaeological literature.

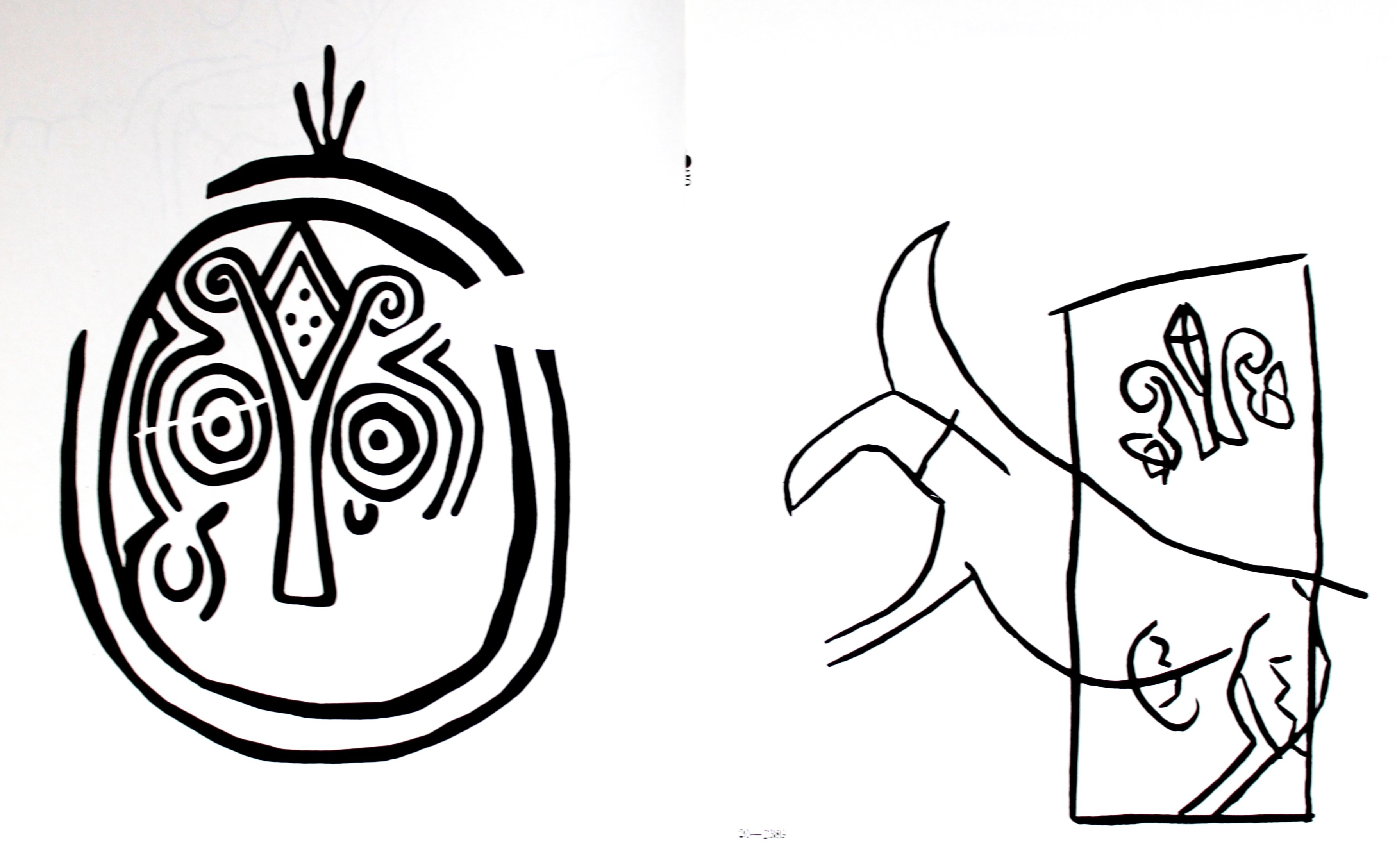

Moreover, the petroglyphs of the Adaevsky tradition have an exceptionally rich and complex artistic language. Their graphic system consists of iconic, symbolic, and index symbols. A structural analysis of these transparent and incredibly compacted paintings reveals that the fundamental mythological subjects have striking similarities to the mythologies of the Old (from Phoenicia and Japan to Scandinavia) and New Worlds.

In many cases, the compositions are constructed according to a binary contrast and counterpoint. They combine different spatial and temporal systems. Realistic images of the animals are accompanied by extremely schematic signs and Arabic inscriptions in the Turkic language (according to the preliminary conclusion of S. N. Muratov, a famous Turkologist). The demonologic characters armed with guns have phallic cases with brushes on their guns’ props. All this needs to be further investigated.