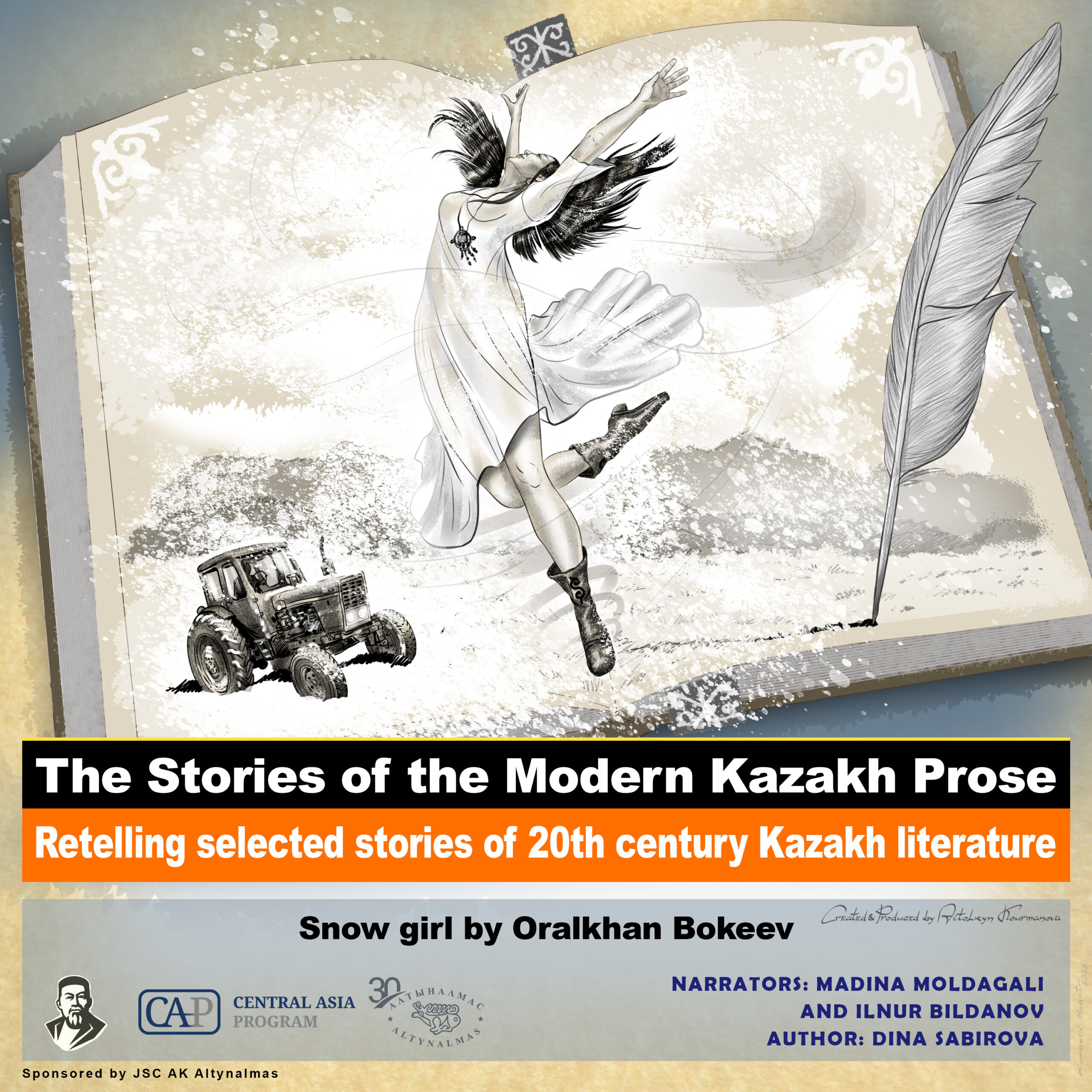

Oralkhan Bokeev (September 28, 1943 – May 17, 1993) was a Kazakh writer, playwright, and journalist. A bright and sensitive writer, a master wordsmith, Bokeev told his stories vividly and with deep knowledge of human nature. The plots of his stories are based on memories of his homeland and the events of his youth. He was proud of and sincerely loved his kind, honest, and hardworking countrymen. His worldview was often expressed in metaphor; each hero of a Bokeev work is a mystery.

“The themes of my novellas and short stories are inspired by memories of my native land and the events of my youth,” wrote Bokeev. “My countrymen, the Kazakhs, are strong, honest people with open hearts. As if enchanted, they live in the area favored by their ancestors. Devoted to their native land, they are proud, hardworking, and brave.”

Full text

It was snowing. It had been a long time since people had seen such a snowfall.

Nurzhan was an advanced tractor driver. The authorities sent him out in a dangerous snowfall to get hay from a remote village. Nurzhan asked his childhood friends—who, like him, had grown up not knowing their fathers—to accompany him. These were hard times. There had been a famine for several years. The kolkhoz was subsisting on the last of its resources. There wasn’t enough money. Amanzhan and Bakhytzhan supported their friend and decided to go with him on this dangerous journey. Before their trip, the friends visited the bathhouse, then the village club, and then the cinema.

That night, half asleep, Nurzhan saw a girl in a white dress. Was it a dream or reality? He could not tell. There were legends about this girl—a snow girl who was able to see misfortune and famine.

Leaving the village, the three friends were very worried and drove in silence. The weather was cold.

In the midst of the snowstorm, late at night, Nurzhan, Bakytzhan, and Amanzhan came across a lonely house. There lived an old man who took them in for the night. Contrary to the traditions of the Kazakhs and the laws of the steppe, he asked the travelers to pay a fee for their night’s lodging. This angered the young men. The owner asked for their boots and watches, which was too high a price. The friends wanted to argue, but the old man demanded a watch at gunpoint. Amanzhan tore the watch from his wrist and threw it to the old man, who deftly caught it, just as a dog catches a hunk of meat. “A konkai soul!” shouted Amanzhan.

The gun trembled in the old man’s hand; he lowered it and, straightening up, stared attentively at Amanzhan. Then he asked who had told him about Konkai. Amanzhan replied that his mother had once told him a story about a villain named Konkai! She called the meanest soul Konkai.

The old man lashed out and hit Amanzhan. But the young man was stronger; he wrested the gun from the old man and fired it in the air (obviously not shooting to kill him). After the shot rang out, an eerie silence fell.

—“Aksakal, tell us who you are?” Nurzhan dared to break this silence.

—“I’m Konkai!” the old man answered sharply and without delay, as if he had been waiting for this question.

—“The same Konkai? But I heard he died a long time ago… Fifty years ago, they say!” Nurzhan exclaimed in surprise.

—“Konkai will never die!” the old man answered proudly and with flashing eyes. “And the fire in the hearth of this house will never go out! Konkai was here before me, I came in his place, and the next Konkai will come in my place! And now he is, perhaps, among us. Because Konkai sits in everyone’s liver, in his brain and in his heart. Konkai means: take whatever you like and don’t be afraid of anything! Konkai is: I want, but I don’t give a damn about you at all! And he sits in everyone, in everyone, but not everyone wants to admit it. Here, you are Konkai!”

Jumping up from his seat, the old man rushed to Nurzhan and poked him in the chest with his finger.

—“And you too!” he squealed, pointing to Amanzhan.

—“And you’re Konkai!” He pointed to Bakytzhan. “Each of you has a Konkai soul too! The milk has not yet dried on your lips and you already want to destroy a person. But you cannot! Here, in these mountains, I have been living alone for fifty years, and no one who has come to my fire has dared to say a word to me. Because I am the master here! Even the authorities from the district, from the region, do not touch me. And you? Do you want to take over me?”

He rushed to the chest, removed all his things and, throwing back the lid, began throwing armfuls of valuable skins on the floor: mink, sable, otter, wolf, bear.

— “Do you see this?” the old man kept saying, heaping up ever more furs.

The zhigits were numb; Bakytzhan slowly crawled on his knees to the chest and began to touch the skins, while Amanzhan shook his head and said: “So be rich!”

—“What did you think? As long as I have all this, I fear neither God nor the authorities.”

And the old man lovingly stroked the shiny deer skin.

—”Know, silly, that the hats on the heads of all the bosses and the collars on their wives’ fur coats all come from me, from this chest. Yes, if I strangled all three of you like kittens and then wanted to justify myself, these skins, I think, would be enough to save my own skin. Or don’t you know that death can also be bought?”

“You want to say, father, that you can, then …” Bakytzhan began, stuttering. “Or I can if I…

— “I want to say that when in the last century Alibek, son of the Kokchetav Sultan Zalkara, committed a murder, his elder brother sent forty black pacers to the Russian capital as a gift to the White tsar. And what? His younger brother was freed. So there! In those days, offerings were taken openly, without hiding, not like in our days …”

Konkai is egotism, when you take whatever you want and do not regret or think about the consequences. The old man said that he was not a villain, but only wanted payment for his services. That he has many patrons and he has nothing to fear.

After the old man left them for the night, the friends began to quarrel and say hurtful things that they later regretted. In the morning, Konkai showed them the way. The cold did not let up; frost formed on the travelers’ hair, making it appear gray. By the end of the third day of their journey, they were convinced that the old man had pointed them in the wrong direction.

That evening, the young men realized that they had lost the sled—and there was no way they could return for it because they couldn’t climb the mountain again. Their concern now was not the sled, but saving their own lives. A fierce, predatory night was approaching from all sides, and there was no way to keep warm. There was not a twig around to build a fire, only smooth hills of white ridges. They could only howl like a wolf, cry like a helpless child. For the first time in their lives, each of them saw that the world could be impossibly cold, merciless, and cruel. Depressed and scared, they managed to build a snow deck on the leeward side, like a house. They climbed up there and tried to cheer each other up and not fall asleep.

In the morning, the friends began to feel sleepy. The three zhigits, silently lying in the snowy house, having gone into their thoughts, gradually began to sink into an insidious dream, and soon their numb souls were carried to the unsteady borderline between life and death. Now only an unforeseen event could save them.

The Snow Girl entered the white yurt where Nurzhan lay. She went up to him, bent down, lifted his head, and whispered, looking imploringly at him: “Get up, get up quickly, my zhigit! The sun is already high.” But no matter how hard he tried, Nurzhan could not lift a finger. His whole body had turned into a motionless, heavy block. And then he said, “Who are you? An angel or a human?” The girl replied, “You know… I am the Snow Girl.”

Nurzhan felt stronger. He turned around and saw Amanzhan and Bakytzhan lying motionless. To wake them, Nurzhan broke the low snowy ceiling, but to no avail. Nurzhan then began to shake his comrades and pinch their cheeks. Gradually, they began to come to their senses. Nurzhan had succeeded in waking up his friends.

Having woken up, they found some sticks and made a fire, then boiled water and poured it into the tractor’s engine. Life returned to their frozen bodies, but their minds were somehow broken. They quarreled about what to do next. One of the friends was found eating the food he had hidden for later, while Amanzhan—scared to go further—began to threaten his friends with a knife, demanding that they return home. The preceding days had somehow changed these old friends.

The zhigits continued on their way. Suddenly, they noticed an old man in the distance. They drove up. The old man offered them food and accommodation. Seemingly abandoned on the very edge of the world, like a lost lamb, his small hut was a warm haven of peace and silence. The old man’s wife offered the young men food and plenty of hot tea with milk. The old man told them a story about the Snow Girl.

An eighteen-year-old girl took her mother to the hospital. On the way back, she was passing by the Konkai’s place. She was in a hurry—the cattle at her house had been left unattended. And, like you, she began to ask Konkai about the short way. And he, having drunk the blood of a deer, jumped like a beast and attacked the poor girl, dishonored her … In her shirt, barefoot, she ran into the middle of the night and got lost in the snow. Nobody has seen her since, son. Either she froze or the wolves ate her … Since then, they have been talking about the Snow Girl. She wanders through the mountains in white clothes, barefoot, with silver hair. And then rumors spread that she had been seen at Konkai. They said she had lived all this time with him, and when she became pregnant, he took her to a distant village and left her on the road. It was said that Konkai was afraid that people who hated him would wipe him out of their memories, so he wanted his descendants to grow up in obscurity, in the crowd of people.

Nurzhan was impressed with the story. The old man went on to mention that his own daughter, who lived with them far from civilization, did not see people and helped them with the housework. Her name was Almashash. The guys did not see her but heard her voice—which perfectly matched that of the Snow Girl. When leaving the old man’s house, Nurzhan turned back—in the window, he saw Almashash watching him leave.

***

Konkai is a symbol of extreme egotism and anarchism—the image of a person who has deliberately fenced himself off from civilization. He is still part of nature, which, in Kazakh stories, is often cruel and indifferent. And as we see, he can poison souls as much as nature and the cruelty of life can.

The origin of the image of the Snow Girl is a poetic version of the ancient myth about Mother Earth in her female incarnation: Umai-sheshe. The ideal female spirit appears only to a pure soul, a sinless person. Nurzhan appears as such in the story; in his soul he is a poet, a romantic. The philosophical background of this mythopoetic layer is as follows: only love, only a lofty dream, can save us from the cold of alienation, loneliness, and ultimately moral degeneration. The main message of the work is not to let yourself become Konkai, even amid cold, hunger, and despair.