Anuar Alimzhanov was born on May 2, 1930, in the village of Karlygash in Taldykorgan region. From 1963 to 1967, he worked as editor-in-chief of the Kazakhfilm film studio. He is considered one of the most prominent Kazakh writers of the late Soviet period. He wrote not only stories about the contemporary period, among them “Fifty Thousand Miles by Water and Land,” “The Caravan Goes to the Sun,” and “Blue Mountains,” but also such notable historical novels as “Souvenir from Otrar,” “Steppe Echo,” “Arrow of Makhambet,” “The Messenger,” “The Throne of Rudaki,” and “The Return of the Teacher.” Alimzhanov was also a major public figure who greatly influenced the society of his day. From October 29 to December 26, 1991, he served as the elected head of the Council of Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Under his chairmanship, the Council of Republics adopted the Declaration of the Termination of the USSR, recognizing the Belavezha Accords and the creation of the CIS.

FULL TEXT

In the town of Demen-kuduk, sheep on a state farm huddled near a huge dry trough. The animals had been without water all day. Six shepherds, heading to their wintering grounds, had driven their flocks here, hoping to find water. But there was no water. With difficulty, the shepherds extracted several pots of water from the bottom of the well. The sheep licked dry stones in despair.

One of the shepherds, named Fazyl, was sent for supplies and help. He was given a camel and verbal instructions on how not to get lost. Fazyl was worried that there might also be no food in the village. Maybe there would be help from a small geological expedition working in the sands, looking for deep water.

Five shepherds remained near the flocks: four old men and one woman. The woman was younger than the others, but the wind and sun of the desert had stripped the beauty from her face. All five were silent. They went to look for another well, but it also turned out to be empty. The closest well, Shabdan-kuduk, was 30 kilometers away.

“Only the coolness of the night can save the flocks”, – said one of the shepherds. “If the heat of the day catches us on the way, then death will begin. But which of us will lead the flocks into the dark night? After all, there are many paths in the sands, and you can easily get lost between the dunes.”

He slowly turned his head to look at the woman. “The guide must have strong legs, keen eyes, and great strength. Rym, daughter, only you can guide us through. You know every trail here.”

By morning, they had to reach Shabdan-kuduk, where there was water and food. This was the best pasture in the whole area. Rym thought about old Shabdan, whose name had been given to the well to which she led her flocks.

It was Rym’s first day of work as a shepherd. She could not gather and hold a flock of sheep. Suddenly, an old man appeared at the top of a distant dune. He walked straight toward her, having recognized Rym immediately. Shabdan advised her to choose the highest dune and watch the sheep from there.

Now, she was not afraid of losing the sheep. She knew that the sands were not deserted—that behind every hill, there could be a kind person who would come to the rescue. In the steppe, she met her husband, Fazyl. Shabdan and Fazyl taught her how to navigate the dunes in order to find good grazing; how to avoid thirst in the desert; how to find water and take care of the sheep; and how to help others.

It was Shabdan who first told Rym about Madamar. One day, after Shabdan took a drink of water, he thanked a certain Madamar and wished him eternal happiness. Rym asked who Madamar was. “Young people need to know the history and secrets of their steppe,” answered Shabdan, adding, “Everyone who quenches their thirst from the wells of the Muyunkums and Kzylkums should thank Madamar.”

“All the shepherds know about Madamar,” Fazyl began. “Madamar is not the real name of the man I’m talking about. Madamar was the name of his grandfather, a famous well-digger; it was also the name of his father, an equally skilled well-builder. The one Shabdan-ata spoke about also became a well-digger. From childhood, he wandered along the sands behind his father and learned to recognize the flow of underground waters from the lonely, stunted bushes. Madamar knows the secrets of the desert. He can accurately determine the reasons why the water level in a well is falling or why abundant thickets of camel thorn have appeared in a given spring. Madamar works all year. And in the summer, he wanders for days between sand dunes in search of hidden waters. He digs a well, strengthening the sand centimeter by centimeter with the roots of juzgen grass, intertwined with koyan-shop, which he prepared in the summer. The roots grow into the sand, and Madamar’s well never crumbles. All shepherds, all wanderers who have ever crossed our sands, know about this.”

It is said that three-quarters of all Muyunkum wells were built by Madamars. And our Madamar is now in his eighties, he lives in our own Sarysu district. Only I don’t know his real name. Everyone calls him by his grandfather’s name. This name has already become a symbol of nobility. He is a great friend of our grandfather Shabdan. The shepherds say that their friendship began a long time ago, back in the 1930s. Madamar, like grandfather Shabdan, is uncommunicative and taciturn. All his life, he has been doing good deeds for people for free. He has a dream, inherited from his grandfathers—he dreams of the day when the Muyunkum underground sea will be under the control of the desert man.

“Underground sea?” Rym asked. It was the first time that she had heard about this.

“Yes, there are underground seas here, they lie under our sands. Madamar believes in this, which means it’s true,” Fazyl replied. “I wanted to be like Madamar and Shabdan-ata, so after school I became a shepherd. I want, like them, to do good deeds for people, take care of herds, find water.”

Together with Fazyl and Shabdan, Rym grazed herds of collective-farm sheep in the endless deserts of Muyunkum. She had a daughter, Saule, who studied at a music school in the city. Perhaps, Rym thought, she would become a musician like her great-grandfather.

Rym thought about old Shabdan and the last day of his life. Just like today, they had wandered for a long time in search of water. Shabdan had found the ruins of ancient buildings. From the grasses and thickets of saxaul, he determined that there had once been water here. Shabdan found a well and drank the water, and once he was sure that the sheep were safe, he died. The new well was named after Shabdan.

Then Rym’s thoughts went to Fazyl. Where was he? Had he reached the village or got lost in the sands? Was he wandering the sands, mad with thirst?

Finally, Rym and shepherds reached Shabdan-kuduk. Rym slowly approached the well and knelt down. The water reflected her face, roughened by the wind, sun, and heat; her eyes, filled with tears, shone. Peering into the mirror of the water, she saw an endless blue sky above her head.

Completely exhausted, people lay on the sand. The last crumbs of cottage cheese had already been eaten. Rym sat with her gaze fixed on her feet. She was tired and wanted to sleep. A sick old shepherd was sleeping next to her. The sheep had been saved. They scattered around the tract and greedily plucked rare blades of grass.

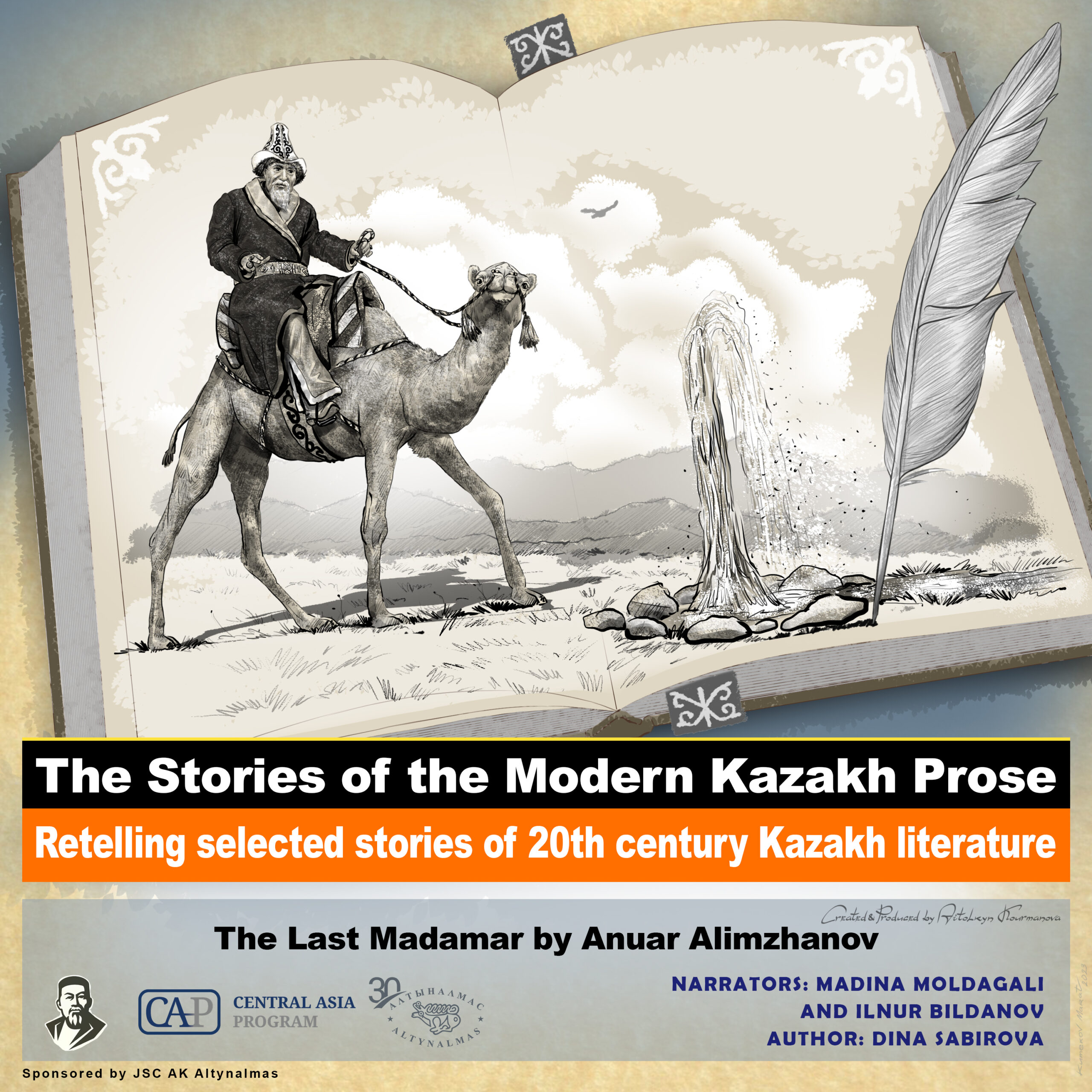

Suddenly, a helicopter appeared. It was Fazyl, who had flown in with rescuers to help them. Fazyl said that he had met Madamar in the sands. On his camel, Madamar had taken Fazyl to the camp of the geological expedition, and the geologists had immediately dispatched their helicopter with food for the shepherds.

At the camp, Rym met Madamar. He was a tall, broad-shouldered, sunburned old man with a gray beard. But his eyes, it seemed to Rym, were surprisingly clear and calm. “Shabdan-ata told me about you,” Rym told him.

“Shabdan?” Madamar turned his head and looked thoughtfully and sadly at Rym. Then he turned his gaze back to the workers, who were excitedly watching the drilling progress.

“Now! Now there will be water!” a young geologist suddenly exclaimed, choking with delight. And before he had time to finish the next sentence, a huge fountain sparkled, bursting out of the ground. The water splashed over everyone. The workers scattered, laughing and shouting with joy. But old Madamar did not move. He stood like a statue, streams of cold, clear water flowing over his gray hair, faded beard, and wrinkled face and clothes. The old man’s eyes were closed, and no one saw his tears.

“Shabdan, did you say Shabdan, daughter?” He turned to Rym again. “He was a good man. And this is his dream.” Madamar went up to the camel lying near the tent, untied his small shovel from the saddle and gave it to the young Kazakh geologist. “Thank you, son,” he said, and, saying goodbye, climbed onto his one-humped camel.

“The last Madamar is leaving the desert…” Someone laughed but stopped as the young geologist looked at him sternly. “He was the one who made me fall in love with the desert. We’re from the same village,” the young man said very quietly. “This is the last well-digger of our desert; our whole region knows him. It was not I, but he, who found water here.”

The sun was setting down and a mighty fountain was rising into the evening sky. Madamar went into the dunes. And perhaps only Rym guessed that he would not return to the village but would go to the shepherds and walk his last journey through the sands. This is what all Madamars do.

***

For Alimzhanov, Madamar is the keeper of national culture, treating the land and nature with the care of a real master. We meet this true master only at the end of the story, when he magically appears to save his people by finding underground water. A rare woman among the nameless shepherds, Rym unites different eras, accepts the ancient idea, and cherishes it to pass on to her family. Rym, her husband, and a young geologist learn from the old Madamar and Shabdan how to survive in harsh natural conditions and serve people with self-sacrifice.