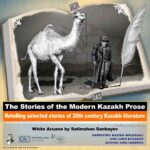

Satimzhan Sanbayev is a Kazakh writer, film actor, and screenwriter. He won the Prize of the Union of Writers of the USSR in 1981 for the best novel about a working man. Born into the family of the prominent Kazakh teacher-educator Khamza Sanbayev, in 1967 he was invited to star in the film “The Road of a Thousand Miles.” During filming, he completed his first story, “White Aruana” (White Camel), which was published a year later in Prostor magazine. This and his next story, “And the Eternal Battle!…” captured his audience thanks to their deep ideological and philosophical content. Sanbayev penned dozens of vivid literary essays, stories, and novels that have been published in more than 30 countries worldwide. Sanbayev himself was a noted translator: he produced the first complete translation into Russian of Abai’s Words of Edification.

FULL TEXT

On the seventh day, Aruana—a young, white dromedary camel—disappeared. The old man Myrzagali went looking for her. He began to think the wolves might have eaten her—but he couldn’t find any bones. Only on the fourth day did Myrzagali find Aruana 100 kilometers from home. It appeared that the camel had fled west to Mangistau, the place where she had been born and where the old man’s daughter, Makpal, lived with her husband. When the old man found the camel, he excitedly started talking to the camel as if she were human: “Your mother is gone, and you, perhaps, were given to me so that people would not hear your crying. Silly you, would I agree to take you if she lived?.. ”

Now the white dromedary camel Aruana was tied to the neck of a neighbor’s camel. Winter came; Aruana changed, grew taller, and her wool looked like a white cloud. The neighbors grew jealous of the old man. Sholak, his neighbor, offered to exchange two camels of a local breed for the one-humped Aruana.

Sholak and Myrzagali were not only neighbors, but longtime friends who had worked together in the oil fields of West Kazakhstan before the Second World War. Myrzagali had married his wife, Asima, before the war and she quickly became pregnant. By the time Myrzagali, who served throughout the entire war, returned home in 1946, after being treated in the hospital for a concussion, his daughter was already five years old. The girl was the spitting image of her father. Sholak served only in the first year of the war before being wounded and returning home, where he worked as a wool collection agent. Toward the end of the war, Myrzagali’s wife, Asima, had a brief affair with Sholak.

After the war, Myrzagali returned home and moved back in with his wife as though nothing had happened. Many condemned him for having an unfaithful wife, but he appeared unconcerned, seemingly focused instead on his dream of establishing his own farm before he retired. He therefore acquired a dromedary camel, Aruana, from the west of Mangistau. Aruana became the sole object of the old man’s affections, but the camel seemed odd: she always tried to keep herself separate from the herd and—as people gossiped—was too proud of her own physique and the exceptional beauty of the breed in general.

After the war, Myrzagali could not have any more children. Sholak wanted to marry his son to Myrzagali’s daughter, Makpal, who had grown up to be very beautiful. Myrzagali refused. He loved his daughter very much, and visited her often after she eventually married and moved far from home, to Kulsary.

The old man returned from one of these journeys to Kulsary upset. Makpal and her husband—a young engineer—were quarreling, and their child was sick. Myrzagali scolded both young people and left without even spending the night. Extremely upset, he went for a drink at the train station before his train departed. On the train, he quarreled with the conductor; they were rude to each other, and he moved to the next car. There, the fellow travelers turned out to be unfriendly and the radio blared the entire time.

When he finally returned home, he was told that Aruana had fled again.

He found Aruana the next day far beyond Kulsary. Aruana was marching straight toward Mangistau, and when she saw the rider, she ran. Myrzagali spurred his horse, shouted: “Hey!”—and in his cry there was more resentment than joy. The horse sped up. But after a while, Myrzagali noticed that Aruana was running effortlessly and with speed, stretching out her long neck and raising her legs high, while the horse did not cut the distance between them at all. An hour passed, then another… The horse was breathing heavily, the veins on his wet neck swelling with tension. He was considered a good horse, took prizes at baiga, but the distance between him and Aruana hardly decreased. Until evening, they jumped a few more hills and a small river—a tributary of the Zhem. At night, they passed the dried-up lakes of Zhalpak—this place was bumpy and wild. On these hillocks, with their frequent ascents and descents, Aruana began to give up. By morning she was running hard, stumbling over bumps and falling to her knees. Then she gave up. The horse caught up with her when the sun rose; Aruana walked heavily, dark with sweat, staggering on her long, weakened legs, but she continued to walk and did not look back. Myrzagali caught up with her and, bending down, grabbed her leash. The tired horse stopped by itself. And Aruana screamed for the first time. She screamed thinly and plaintively, and the old man shuddered at this heart-rending cry and tugged at the leash to stop the crying. But Aruana did not let up. And so Myrzagali jumped to the ground, hugged her by the neck, and also began to cry.

After the trip, the old man fell ill and did not get up for several days. He did not like going to doctors, so when Asima mentioned seing a doctor, he grew angry and yelled at her. But the doctor nevertheless came and examined Myrzagali. Seeing her husband’s frail state, the still-beautiful Asima burst into tears, remembering the past.

It was decided to send Myrzagali for rehabilitation. While he was being treated, Asima took good care of Aruana and fed her at home, remembering what the camel meant to her elderly husband.

Four months later, when Myrzagali returned home, he found an adult camel—a beautiful she-camel ready to breed and give precious and nutritional milk. But there was no dromedary male in their district, so the old man took Aruana to mate with a Bactrian male in a neighboring village. Aruana did not want to—she fought every attempt at mating. Her eyes popped out of their sockets; she screamed wildly, as if she had been brought not to the male she needed, but to a wolf. She lay down only when Kokaidai, the owner of the male camel, began to beat her legs with a whip. Myrzagali stood aside. Aruana touched the snow with her belly and immediately jumped to her feet, but Kokaidai pushed her down again and wrapped the rope around her legs. She thrashed, trying to get up, when she saw the male approaching her. The rope dug deep into her body, but she seemed to feel no pain.

Then she could not get up for a long time. She trudged home in silence, and Myrzagali, knowing that now he had to be very careful with her, felt shame—he chose the flattest path he could. But the she-camel did not seem to appreciate it.

Aruana bore no offspring and all attempts at breeding seemed to be fruitless. Myrzagali wanted to take her to a dromedary male, but due to the state of his health, Asima forbade him to go far to the West, to Mangistau.

People told Myrzagali that he needed to sell the camel, as without offspring there would be no milk. But in the end, the neighbor, Sholak, found a solution: while Myrzagali was absent he cut Aruana’s eye veins and bred her with a Bactrian male. The she-camel could not see anything and the male camel finally got in.

After the act, Aruana trembled frequently and uncontrollably. She seemed to have shrunk in one morning, aged; her wool fell off, became dirty. Moaning, she weakly shook her bloody head; her eyes were tightly closed, and peas of red blood fell from her long brown eyelashes.

Asima was surprised to see that the she-camel had suffered so much from having the veins cut. This was sometimes done to Bactrian camels in auls, but it didn’t cause them this level of suffering; it just made their eyes water all the time.

But it seemingly paid off: Aruana gave birth. She herself became blind, as if cursed by the neighbors’ envy. She gave a lot of milk. She learned to follow another camel. But knowing Aruana as well as he did, Myrzagali became wary of her habits. Aruana grew bolder. For hours, Myrzagali watched how Aruana quietly followed her two-humped camel, raising her slender legs high and placing them carefully, as if feeling the ground. Life had long taught her this gait. She walked smoothly, despite her blindness, and from a distance it seemed that a white, weightless cloud was floating behind this small camel.

At noon one day, Myrzagali could not find Aruana. She had fled again. She had fled blindly to the smell of the wind, taking her offspring with her. Her white-gray baby was afraid to pass the river, but she called him and they ran together. Myrzagali and Sholak jumped on their horses to find her. Aruana felt the chase and ran even faster. Now she pushed the baby camel aside; she wanted to run so quickly that she ran along the dangerous salt marsh lake, driven by a powerful instinct. Her baby caught up with her, did not let her go further. She flung him away with her teeth and kept running.

Myrzagali and Sholak saw that Aruana had taken the path to the left to the cliff. Sholak chased her with a knife. Myrzagali stayed behind. He stopped, paused, hugged his horse around the neck and wept. From behind him, Sholak cried out. Myrzagali took the horse and the baby camel and led them home, where his old wife waited for him.

***

White Aruana is another fine representation of nature-human relations in Kazakh classic literature. Aruana is almost anthropomorphic: she transforms from an ugly teen camel into a beautiful female too proud to mate and too lonely to love. Myrzagali felt similarly: he had trauma from war, troubles with his wife, jealousy toward Sholak, and resentment of his daughter who had moved far away. He felt more strongly toward his camel than toward his own wife or daughter, but with Aruana gone, he finally experienced peace in his family life while raising her little gray-white camel.