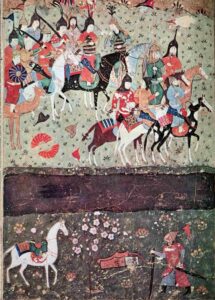

There are important data on the costume of early Turks of the 7th-10th centuries CE in petroglyphs found across Inner Asia from the mountains of the Mongolian and Russian Altai and Tuva to the central Tian-Shan in Kyrgyzstan and Karatau Mountains in the middle Syr Darya basin. In a number of cases, of course, dating them to the early period of Turkic history may be problematic, and despite the large number of such compositions, there is very little detailed and realistic depiction of costume in them. Of additional value are images on the coins of Chach (Tashkent Oasis) of the 7th-8th centuries CE (see, e.g., Shagalov and Kuznetsov 2006; Babayar, 2007) and the Oguzes of the lower Syr Darya in the second quarter of the 9th century (Goncharov and Nastich, forthcoming) and on several metal artifacts from the territory of the Khazar Qaghanate. These data have not yet been completely analyzed.

In important ways, this material supplements evidence derived from well-dated monuments of Chinese Sogdians in the second half of the 6th century CE, from Early Tang burial figurines (mingqi) of the 7th-8th centuries (Yatsenko 2009), and evidence from wall paintings of the mid-7th century in the “Hall of the Ambassadors” in Samarkand/Afrasiab (Yatsenko 2004). The new data also supplement that derived from analysis of early stone statues (see, e.g., Kubarev 1984; Baiar and Erdenebaatar 1999; Ermolenko 2004)1 and from the remains of authentic clothes in tombs (Kubarev 2005, pp. 26-56; cf. Kubarev 2000, pp. 81-88). These sources provide information almost exclusively about male costume. Personages who themselves may not be Turks may nonetheless sport costume with elements that suggest Turkic ethnicity. We see this in Sogdian (Yatsenko 2006, pp. 239, 240, 282) and Early Magyar/Hungarian depictions of the second half of the 9th century (Bokii and Pletneva 1988, Fig. 5.1; Komar 2008, p. 216), where it seems the interest is in emphasizing prestige elements of costume, and in the case of the Magyars it is a matter of borrowing Turkish iconography. It is important first of all to establish which elements of numerous details of silhouette, cut and décor were accentuated. In so doing, we make the a priori assumption that the elements of costume emphasized in Turkic petroglyphs may well differ from those in official court wall painting (Samarkand/Afrasiab), on coins, or in the examples from China. While these latter sources would seem to focus on the elites, the petroglyphs may often embody representations and values of ordinary nomads.

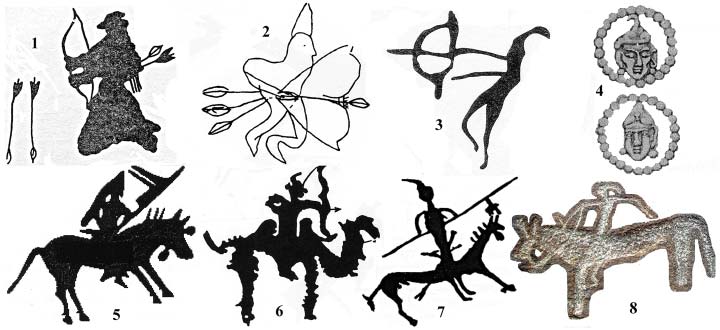

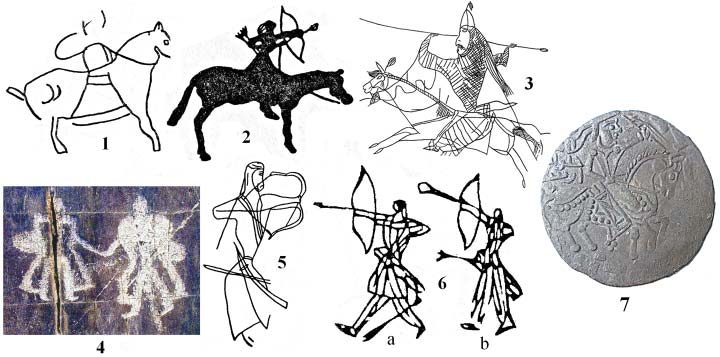

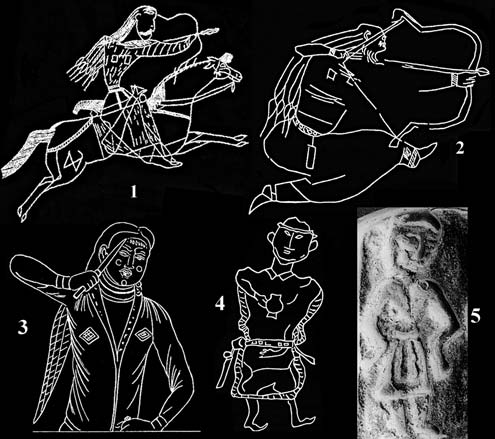

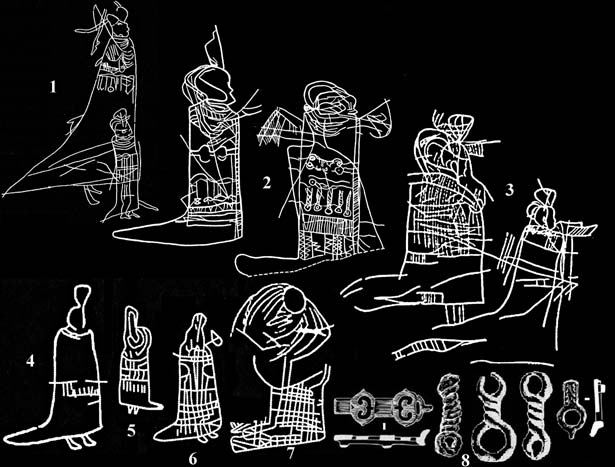

One of the first distinctions between the depictions in petroglyphs and those on coins, murals and mortuary beds is the emphasis in the former on the individuals’ heads. In depictions of various types, headdresses and hair-dos (believed to be a receptacle of the soul and the most important distinguishing feature of an adult male) were of special significance for both creators and viewers. A cone-shaped headdress is the most popular type: high ones (Tsagaan Salaa IV, NW Mongolia; Jetysu/Semirech’e, SE Kazakhstan; Northern Tuva)[Fig. 1.2-3, 6-8]2 and lower ones (from the Jetysu to the middle Syr Darya region) [Fig. 1.1, 4-5]. Occasionally (from Jetysu up to the middle Syr Darya), the lower edge is turned up and has a turned-up flap [Fig. 1.4 lower]. Such a cap used to be made both of dense felt (such depictions of headdresses with standing crowns are known in Jetysu and other districts to the east) and softer fabrics (Northern Tuva; Tsagaan Salaa IV) [Figs. 1.1; 6.7]. Hats with flaps to protect the ears in winter were another widely spread type. These flaps are usually depicted as projecting out and upwards from both sides [Fig. 2.1-3]. Images of them have been found at Tuekta, Russian Altai, in Tuva at Elte-Kizhig and at Jetysu.

Diadems of fabrics with long drooping ends were repeatedly depicted on metal appliqués in the territory of the Khazar Qaghanate (Verkhnii Saltov, catacomb 40; Subbotitsy, grave 2) [Fig. 3.3, 4]. Diadems have the image of the moon above the forehead (the coins of Chach tuduns) or a trefoil (a horseman bronze amulet from the environs of Minusinsk) [Fig. 3.1, 5]. They are much more modest in décor than crowns of qaghans, such as in the Bilge Qaghan burial of 735 CE (Bahar 2002) [Fig. 3.6]. A low cylinder-shaped hat [Fig. 2.4, 5] is shown on coins from Chach and in the depiction of the epic hero on the Khazar ladle pot found at Kotskii Gorodok in the lower Ob’ River, western Siberia.3

Other types are known from single depictions: a wide-brimmed hat (Tsagaan Salaa IV; Kurgak in the Russian Altai) [Fig. 4.1, 6], a narrow-brimmed one (Chach coins) [Fig. 4.3], a small cap made of four triangular pieces (Kyrgyzstan; Zevakino in the Kazakh Altai) [Fig. 4.4, 5], a headdress with a wide projection at the back of the head and a hole for plaits (a bone object of the 7thcentury from Xyrlets in western Bulgaria) [Fig. 4.7].

We see a very interesting cap on a tudun of Chach (group 6, type 4/1) [Fig. 4.2], the back part of which depicts a grotesque mask of a baldheaded old man with a big nose and a long narrow beard. The numismatists from Tashkent with insufficient cause think that it recalls a helmet with an elephant which crowns Graeco-Bactrian rulers on their coins. A headdress of a warrior-standard-bearer could be decorated with two long vertical feathers (Eshkiolmes, Jetysu) [Fig. 4.8]. Sometimes, during special rituals naked men performed in masks of wolves, which were sacred, originally totemic animals for Turks, as attested in texts of the Zhoushu and the Bugut stele (Kliashtornyi and Livshits 1978, p. 57) and many later materials (petroglyphs at Zhungylshek I in the middle Syr Darya basin) [Fig. 4.9].

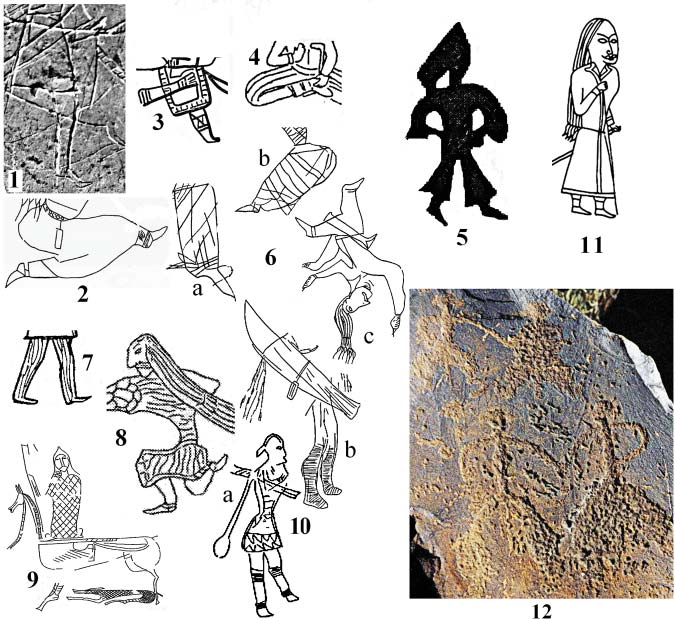

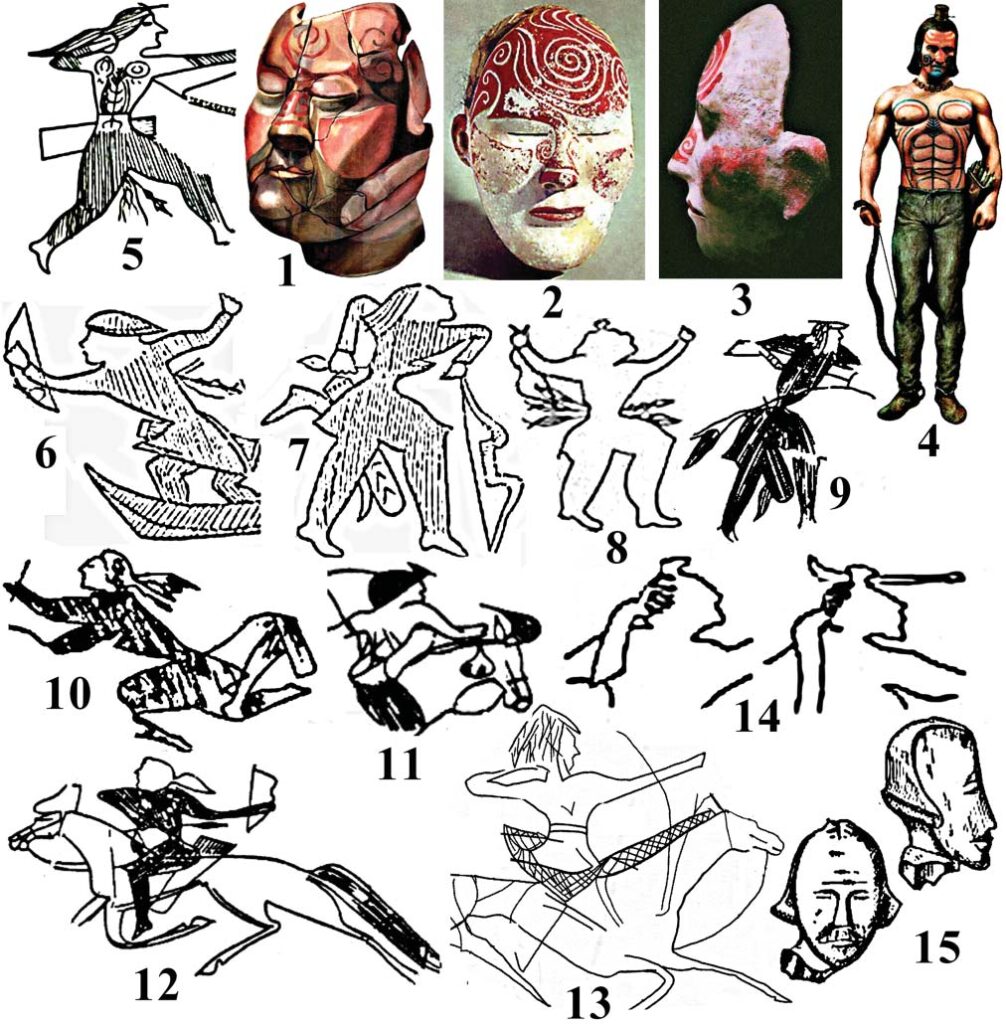

Evidently, several long plaits joined together at the upper and lower parts formed the most widespread type of a hair-do for noble men (Sook-Tyt, Chagan River; Abadzhai, both Russian Altai) [Figs. 5.1; 8.2]. 72 On rare occasions long plaits were divided into two bunches at the sides of the head (a mourning Turk in the wall painting of the Buddha’s Parinirvana, Kizil, Maya Cave [site 3, no. 224]; Chagan River, Russian Altai) [Figs. 7.3; 8.6c]. The plaits might be bound at the top only (Russian Altai) [Fig. 5.2], or interwoven with only the ends divided (Kogaly in Jetysu) [Fig. 5.8]. A clear example of the long plaits divided into two bunches at the sides of the head is in the depiction of the old man on the belt buckle in Hungarian grave no. 2 from Subbotitsy, Kirovograd region of Ukraine) [Fig. 5.3]. Wearing of several short plaits was also very popular (Sulek, Khakasia [Appelgren-Kivalo 1931]; Jetysu) [Figs. 5.4; 6.2].

Sometimes, locks of short or long hair were combed to the sides leaving a small knot at the forehead (Chach coins, group 2, types 4-5 [Shagalov and Kuznetsov 2006, pp. 308-09] and group 3, type 1/1) [Fig. 5.7]. Rarely, locks of hair were spun around a vertically fixed comb (?) as we can see in the depiction of the spear-bearer at Tsagaan Salaa II, Mongolia [Fig. 5.6]. A frontal forelock on a shaven head was, evidently a very rare variant (see only the statue from Taarbol near Arig-Bazhi in Tuva (Evtiukhova 1952, p. 82, Fig. 18); it is known only in isolated cases for nomads of Kazakhstan in the Scythian period and early nomadic Magyars/ Hungarians (cf. Ermolenko and Kurmankulov 2011). Common people wore their hair cut short and combed to the back (Sook-Tyt, Russian Altai) [Fig. 5.5]. A small beard is depicted rather episodically, but long, narrow and practically horizontal moustaches quite often. It was probably an object of pride and special care for the elite. In the opinion of Liubov’ N. Ermolenko, starting at the end of the 7th to beginning of the 8th century CE some Turkic groups adopted the fashion of wearing, in addition to a moustache, a very small, barely visible beard under the lower lip as a mark of prestige (Ermolenko and Kurmankulov 2012, p. 107) . However, it can be seen primarily on statues.

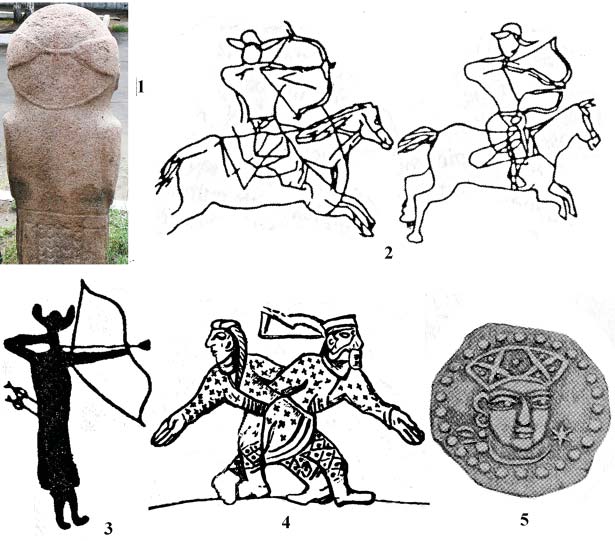

As for the clothing, only on rare occasions was the cut accentuated with lines on caftans and trousers as at Eshkiolmes, Jetysu [Fig. 6.6] or only on trousers (Tarskii, catacomb 6, Northern Ossetia) [Fig. 3.2]. The long-sleeved coats (probably with lateral cuts) are usually found in depictions of walking personages (but cf. the horsemen at Orta-Sargol, Tuva) [Fig. 6.1]. At times they have a deep wrap over to the left (Zhaltyrak-Tash, Kyrgyzstan) [Fig. 6.5]. Long cloaks, open in the front, which were worn thrown over one’s shoulders were, evidently, close-fitting in the waist (Kuldzhabasy, Jetysu) [Fig. 6.4]. A deep wrapping over to the left was marked for them only occasionally (in Kyrgyzstan) [Fig. 6.5]. More often shorter caftans can be seen. Sometimes, vegetal or geometrical patterns on textiles were drawn in detail (the ladle pot from Kotskii Gorodok; Tsagaan Salaa II in Mongolia) [Figs. 2.4; 5.6]. The waistline (often very narrow) was accentuated with a belt (Russian Altai, including the Chagan River, and Kyrgyzstan) [Figs. 5.2; 6.2,3 and 5]; the shoulder line was also strongly emphasized, but less often [Fig. 5.1-2] (in Hyrlets, Bulgaria, shoulders are covered with a cape-pelerine). A narrow waist was a very important element of the proper appearance for a warrior in Scythian times (Yatsenko 2006, p. 101). In fewer cases (for common people) the waistline was not accentuated at all [Fig. 5.5].

Two lapels at the sides of short or long caftans were first marked in the 2nd-4th centuries CE on terracottas in Iranian-speaking Khotan (Xinjiang), then in the Kucha Oasis. Turks of the First Qaghanate (551-603), documented in Chinese depictions, almost without exception do not wear caftans (Yatsenko 2009). However, from the 7th century, two-lapel clothing begins to spread among them (Yatsenko 2006, pp. 252-53, 282-83), even though it is rare in depictions on the territory of the western Khazar Qaghanate. It is significant that, when on silver coins of old Khorasmian design from the lower Syr Darya basin issued by the Oguz ruler Jabuya in the second quarter of the 9th century there appear new elements in the costume of the “Khorasmian horseman” on the reverse, these elements reflect a local Turkic reality — namely, a caftan with two small lapels (with buttons made of fabric at their ends) [Fig. 6.7]. One additional element denoting Turkic costume in these coin depictions is a thick torque, which replaces a previously worn necklace. Long upper garments — shirts that are not open in the front (evidently with lateral cuts in the hem) — are reliably documented in the Abadzhai Valley near the Chagan River in the Russian Altai. There are two square pieces of fabric (?) sewn in front on the breast part of warriors’ clothing [Fig. 7.1, 2].4 The dancer on the early 9th-century saber from Zevakino has a shorter tunic (to the knees) worn closed. Its collar is vertically cut and the long sleeves during the dance allowed to hang loose [Fig. 7.5]. On the image of a man from Kichiku-Bom in the Russian Altai [Fig. 7.4] for some reason the artist attempted to depict two garments worn closed, one over the other. The outer one is knee-length and has a decorative border along the side seams and the edge of the hem and side slits and possibly an attached cape; the inner one is a shirt tucked into the trousers with turned down collar.

Men’s trousers were often worn over footwear; sometimes they were bell-bottomed (Subbotitsy, Eshkiolmes [Figs. 3.4, lower right; 8.5]. Very wide trousers are exceptional — so far they are known only at Bayan Zhurek (in Jetysu) [Fig. 8.12]. There are depictions of completely quilted trousers analogous to those of the Pazyryk Culture (in the Russian Altai) [Fig. 5.2]. As to the types of footwear, ankle boots [Fig. 8.2,4,11] and shoes [8.8a,c, 9] are present in approximately equal proportions. Unlike on statues and wall paintings, we see very few trustworthy depictions of high boots in petroglyphs (Abadzhai in the Russian Altai) [Fig. 8.1]. In Chinese images of the Early Turks, low shoes were more prestigious (Yatsenko 2009); cf. the prestigious image on the Mungut-Khyas stele, western Mongolia [Fig. 8.11]. Shoes with long stockings were used in the Russian Altai (Abadzhai near the Chagan River) [Fig. 8.10]. On the Khazar reliquary from Talovyi II, lower Don basin, barrow 3/1, we see shoes with narrow pointed toe boxes and with tongues at the instep [Fig. 8.9]; for a horseman from Mongolia (Tsagaan Salaa IV) the length of shoe toes was up to 30 cm [Fig. 4.1]. Only in the northern Altai does one apparently see on occasion belts of black fabric (Yatsenko 2009, Fig. 6.8, 9) with two hanging ends [Fig. 7.5] or with an end which divides into three ribbons [Fig. 5.2].

Women’s costume was seldom depicted in detail. We see a silhouette of a lady holding a child by the hand in one of petroglyphs from Jetysu [Fig. 9.2]. She is in a short caftan and wide trousers worn untucked over her footwear; to her right stands a girl (?) in a short jacket and trousers.5 Apparently a narrow anklelength dress, cinched at the waist, is depicted on a girl in a scene of her abduction by two horsemen at SyynChiurek, Tuva [Fig. 9.3]. In all likelihood a petroglyph at Ankeldy (Chu-Ili Mountains) depicts five handholding, dancing women [Fig. 9.7]. 6 They have kneelength jackets cinched at the waist and rather narrow trousers. A long-sleeved coat of the goddess Umai without lapels (on the stone from grave 16 at Kudyrge, Russian Altai) is decorated with horizontal lines of décor, probably a vegetal pattern [Fig. 9.1]. The upper part of the garment is secured with a button attached by a chain (?). A long-sleeved coat of the woman depicted on the ivory plaque from Suttuu-Bulak (Kyrgyzstan) has two lapels and is secured with a fastener at the breast (Khudiakov et al. 1997, Fig. 2). The lapels on one of the statues from Kyrgyzstan have a lining with ornament resembling a row of small circles or rosettes [Fig. 9.6] as is common in Chinese and Sogdian textiles of that period (Maitdinova 1996, Figs. 33; 43.1; 73-74).

The headwear (with three large projections) of elite women could resemble a narrow diadem with some sort of scaly covering (the Umai Goddess in Kudyrge); in all likelihood, the modest height of the main part of the headdress is to be explained by the schematic nature of the depiction. There is also a well-known, more massive cone-shaped headdress with three large projections and a cap band (a turned-up flap) (worn by a wife of the tudun-governor, on Chach coins, group 2, type 4) [Fig. 9.4]. On the more detailed depictions, the lower border of a headdress with such pointed “horns”may be decorated by a tooth-like band. The image of Umai (and her female counterpart as well, the woman from Suttuu-Bulak) accentuates narrow joined eyebrows and an oval face [Fig. 9.1]. Probably it is a female warrior depicted on the ladle from Kotskii Gorodok [Fig. 9.5], with short plaits tucked under the collar of the caftan before battle, her clothes no different than those of her male counterpart (Yatsenko 2006, pp. 340-41). Her sex is determined only by the hairdo, the two comparatively short but thick braids tucked under the collar.7 The important attribute of a woman from a ruling family was probably a gold necklace with a pendant on a lower part [Fig. 9.4]. Umai in Kudyrge apparently wears ankle boots with turned-down socks.

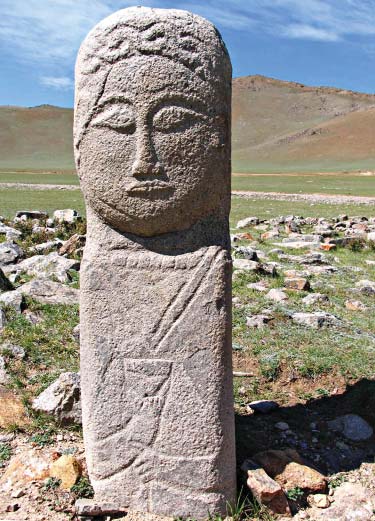

On rare occasions, not only ethnic Turks but representatives of other peoples were reproduced in statues of early Turkic type. In this respect should be mentioned a very interesting statue discovered in 2010 in Zavkhan aimag, NW Mongolia, by Iurii Ozheredov [Fig. 10] which has a combination of a very wide face (close to a square) with wide pupils and a unique (unknown for early Turks) hair-do with curls along the lower edge. In Inner Asia at that time such a hair-do is encountered only for two peoples and only for men who were active, involved in commerce and occupying a prominent position both in China and the qaghanates: Tokharistanians (Yatsenko 2006, Fig. 189: 23-24) and Sogdians. To be precise, for the latter as yet there are no depictions in their motherland, but this feature can be seen among Chinese Sogdians, persons of not the lowest ranks – servants and caravaneers (Yatsenko 2009, Pls. 6 and 10; 2012, Pls. 10, 3 and 13.4). Probably the statue from Zavkhan aimag is that of a male Sogdian. It has an interesting necklace of seven beads (a sacred number). There is nothing surprising about the find from Zavkhan, as participation of Sogdians in creating a series of Early Turkic statues is common knowledge (Hayashi 2006, pp. 245-60).8

On the whole, the appearance of costume on petroglyphs, coins and metalwork differs in many details from that in stone sculpture and wall paintings. The reasons for these distinctions can be found in the differing approach to the choice of personages which is connected with different purposes of the artifacts and compositions (in petroglyphs, common men could sometimes be depicted in scenes of hunting). The differentiation can also be explained by the need for special techniques in processing different materials and the requirements specific to three-dimensional and two-dimensional images. According to Liubov’ N. Ermolenko (Ermolenko 2007), stone statues originally might have had some coloring of many important details, such color is no longer preserved and so far has never been the subject of special study.

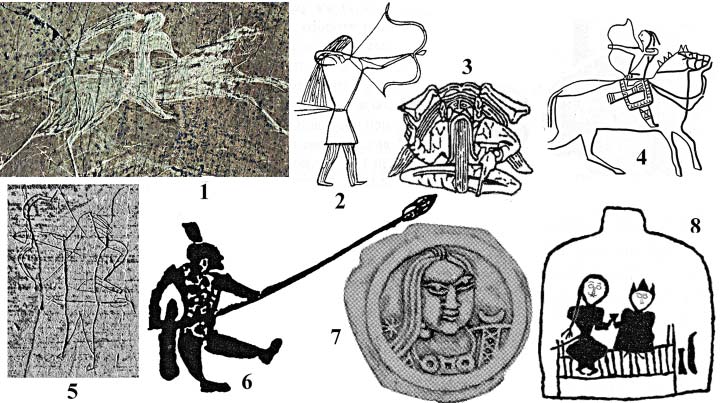

Another interesting subject is the comparison of the costume of the early Turks and that of the tribes of the Tashtyk Culture in Khakasia, who lived to the north of their Xinjiang-Mongolian motherland in the 2nd century BCE – 5th century CE.9 From the later stages of their history we have an important series of detailed carvings whose rendition of details of costume has frequently attracted considerable attention. These include first of all the engraved wooden plaques found in crypt no. 1 near Tepsei Mountain in 1968 (Griaznov 1971), ones found near Tasheba Riva (Podolsky 1998), and the petroglyphs near Oshkol Lake (Pankova 2012). Svetlana V. Pankova concludes that the “Tashtyk peoples” were Turkic speakers, to a considerable degree basing her opinion on the “closeness” of their male hair-dos and the presence in their art of a series of parallels in Xinjiang (Pankova 2011, pp. 25-26).

Unfortunately, all the basic and clearly defined elements of Tashtyk costume which are the most important indices of ethno-cultural identity do not confirm this hypothesis. On the contrary, they are more likely unique and have no close analogies among the early Turks who replaced the “Tashtyk peoples.” Tashtyk women have hair-dos of a Chinese type with decorated coverings on the crown in the form of a Möbius ring made of birch bark [Fig. 11.3] (sometimes two long pins inserted in the coiffure are also visible [Fig. 11.1]). Their dresses have a relatively short train (which probably appeared among the Hephthalites, the enemies of the Turks, in the Amu Darya region and later in Western Europe) but absent covering shawls, belts worn high under the bust with a series of decorative pendants (Azbelev 2009) [Fig. 11.1-2, 8], and capes [Fig. 11.1-2] etc. In general the decorative motifs of Tashtyk textiles are foreign to those ot the early Turks in the cases where they are depicted with adequate detail [see, e.g., Fig. 11.2]. In contrast to the Turks, the men have shorter braids which are woven together (including those where the locks are bound at the back of the head and at the tip) [Fig. 12.10, 12], there is no emphasis on the moustaches, there are very short haircuts, as though shaped with a bowl and with a horizontal edge [Fig. 12.6, 13], their hairdos may have a knot on the crown and be fixed with a pin [Fig. 12.4-5, 14] and with curls at the temples at Yibat II (Vadetskaia 1986, Pl. IX.35) [Fig. 12.15], and finally they may have low and rather wide conic caps (Podolsky 1998, Fig. 1b). In contrast to the early Turks, in the dress of the “Tashtyk peoples” the projecting borders of the hems of the short caftans are meticulously emphasized [Fig. 12.6-9] (Pankova 2005, Fig. 7), but in contrast, the characteristically unfastened outer dress which they in fact wore is not emphasized (cf.. Vadetskaia 1986, pp. 137-38). (This is difficult to explain merely by the dominance among the former of depictions in profile.) In depictions of the early Turks, detailing of the face and of the upper part of the body is not emphasized. [Fig. 12.1-5].

Editorial Notes

Translated by Daniel C. Waugh. This article is reprinted with permission. First published at The Silk Road, Vol. 11 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This article has been prepared with the support of the Development Strategy Program of the Russian State University for the Humanities. It was made possible in part thanks to some partly published and unpublished materials presented by some colleagues (Evgenii Iu. Goncharov, Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Science, Moscow; Iurii I. Ozheredov, Museum of the Archaeology and Ethnology of Siberia, Tomsk State University; Boyan Totev, the Regional Historical Museum of Dobrich town, Bulgaria) and consultations on rare literature by some Siberian specialists (Dmitrii V. Cheremisin, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Science; Liubov’ N. Ermolenko, Kemerovo State University).

References

Full references for this piece can be found in its original publication.

Footnotes

- These statues probably were stand-ins for the deceased at the time of his burial ceremonies and marked the place where one of his souls resided (Kyzlasov 1964, p. 36). ↩

- In many cases Zainulla S. Samashev interprets the schematic depictions of head-gear of warriors as a helmet with plumage (see, for example, at Bayan Zhurek; Samashev 2006, p. 122). In such a case though one cannot understand why a “feather on a helmet” always extends downward, not up, and thus follows the contour of the headgear. ↩

- The inscriptions which accompany portraits of rulers on Chach coins are in one of the Iranian languages (Sogdian). On account of that, in their interpretation one is best to rely on the opinion of iranists (Vladimir A. Livshits, Edvard V. Rtveladze and others), rather than on the turcologist Gaybulla Babayar(ov) (see, for example, Babayar 2007), whose reading of the inscriptions usually is significantly at odds from that by the iranian specialists and presupposes the presence in provincial Chach of the most important rulers of the Western Qaghanate. ↩

- Some Kazakh colleagues even consider these textile insets to be of Eastern Roman origin, like those which became popular in the early middle ages among many peoples of Eurasia and which were embroidered with depictions of specific local clan tamghas (Samashev et al. 2010, p. 54, Fig. 62). ↩

- With no explanation, Zainolla Samashev considers these women to be “dismounted warriors” (Samashev 2006, p. 141). ↩

- The one on the end holds in her hand a kerchief. Under the row of the dancers stands a man who holds in front of him a saber which he has unsheathed (Rogozhinskii 2012, Fig. 5.1–3). ↩

- The adherents of an interpretation of this scene as a duel between two men to date have not provided any cogent and systematic argumentation. Our version thus appears to be more likely, in that the motif of a duel between a soldier and a female warrior hero was very popular in many late Turkic epic poems. Moreover, the two braids which in real life Turkic men [Fig. 5.4] and turkicized Sogdians sported (Yatsenko 2006, p. 240) were much shorter and thinner than that which we see on the warrior maiden. ↩

- The influence of Sogdian iconography is evident also on certain Khazar medallions of the second half of the 9th century CE from upper Don River basin (Aksenov 2001, p. 137). ↩

- For some scholars the end date of the Tashtyk Culture was the 6th century (Dmitrii G. Savinov); for others, the 7th century (Anatolii K. Ambroz, Pavel P. Azbelev). ↩