The Aral Sea catastrophe has been known since the late 1980s as one of the largest environmental disasters in the world. Once the fourth-largest lake in the world, despite being located on the otherwise arid Eurasian continent, the Aral Sea has shrunk tenfold since the 1960s and split into several conditionally independent bodies of water.

Author’s notes: A – the city of Aralsk; B – Kokaral Dam; C – planned Saryshyganak Dam; D – Syr Darya Delta; E – Amu Darya Delta. In 2021, the Northern Aral Sea was measured to have a volume of about 20.0 km3 and salinity of 10-14 g/l; the Western Aral Sea a volume of 42.5 km3 and salinity of 170 g/l; and Lake Tuschybas a volume of 1.7 km3 and salinity of 90 g/l. For comparison, prior to 1960, the Aral Sea had a surface area of 66-67,000 km2 and contained 1,062 km3 of water, with an average mineralization of 10-11 g/l. The average depth of the pre-crisis Aral was 15 m; the maximum was up to 60 m; and the absolute water level varied within 53-54 mBS (meters of the Baltic system).

In the Name of Food, Cotton, and War

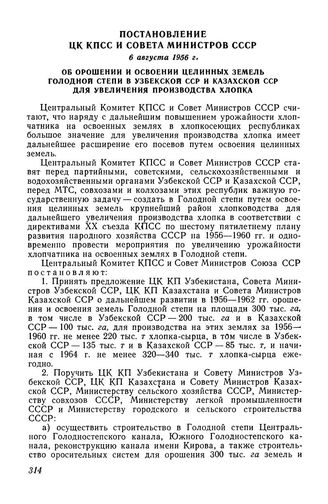

The starting point of the Aral Sea crisis was the withdrawal of water from two great Central Asian rivers: the Syr Darya and Amu Darya. This withdrawal was ordered by a decree of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of Ministers of the USSR dated August 6, 1956, and entitled “On the Irrigation and Development of Virgin Lands of the Hungry Steppe in the Uzbek SSR and the Kazakh SSR to Increase Cotton Production.” This decree became one of the first steps of an ambitious plan—announced in the March 2, 1954, resolution “On the Further Increase in Grain Production in the Country and on the Development of Virgin and Fallow Lands”—to use the virgin territories of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Siberia, the Volga region, and the Urals for agriculture.

The first successes in the development of the Hungry Steppe, in combination with related projects—the construction of the 1,450-kilometer-long Karakum Canal in Turkmenistan, the “regulation” of the Syr Darya’s flow through the construction of a cascade of hydroelectric power stations, and the extensive development of cotton and rice areas throughout Central Asia—made it possible to address major economic problems in a historically short period of time. Chief among these was the achievement of “cotton independence,” which was important not only for the textile industry, but also for the military-industrial complex of the USSR, which was of especially great concern at that time. By the 1990s, the population of the Aral Basin had reached 50 million and the area of irrigated land had increased to 8 million hectares.

These significant achievements of economic development were reached by exploiting the surface rivers of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, which represented the main resource for irrigation and all other related purposes. Although the use of water from these two rivers for irrigation has a centuries-old history, it was only during the Soviet era that attempts at the hydro-reclamation of “uninhabited and fallow lands” took on such a scale. Of course, this had overall positive results for the socio-economic development of the countries of Central Asia. But it also became the main cause of the Aral environmental disaster, the world’s largest man-made environmental disaster.

Siberian Sea Project

The Soviet leadership quickly realized the grave mistake it had made. As early as 1968, the plenum of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) Central Committee instructed the State Planning Committee, the USSR Academy of Sciences, and other organizations to develop a joint plan for redistributing the flow of northern European and Siberian rivers—essentially altering the geography of both the European and Asian parts of the USSR. More than 160 Soviet organizations were involved in this project.

When it came to Kazakhstan and Central Asia, a phased transfer of Siberian water was planned: a withdrawal of 25 km³ of water in the first phase, 60 km³ in the second phase, and 75-100 km³ per year thereafter from the Ob and Irtysh basins, with possible transfer of part of the runoff from the Yenisei basin. To this end, the scientists planned to create a reservoir of 260,000 km²—the so-called Siberian Sea. The latter was supposed to be filled by connecting the Irtysh, Tobol and Ishim canals. The overall goal was to slow down and, ideally, prevent the drying-up of the Aral Sea. But this ambitious project, which sought to continue the development of Central Asian agriculture while protecting what remained of the Aral Sea, never went beyond design and survey development.

Source: e:User:Kapitän Nemo; de:User:Captain Blood, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

By the mid-1980s, five branches of the USSR Academy of Sciences had put forward negative views of this project. A group of academics led by an active opponent of the project, academician Alexander Yanshin, signed a prepared letter to the Central Committee “On the Catastrophic Consequences of Transferring Part of the Flow of Northern Rivers.” Of particular concern to opponents of the project were plans to use “peaceful nuclear explosions” for canal construction, as well as the inevitable flooding of not only floodplains and floodplains, but also historical memorial lands in Central Russia. And although the arguments presented concerned mainly the “European” part of the project, all this could not but affect its “Asian” part. The prominent Siberian writers S. Zalygin, V. Rasputin, V. Belov, V. Astafiev, and V. Shukshin, among many others, joined in criticizing the project. These writers did not speak from the point of view of science and economics but rather emphasized ethical values. In particular, they focused on how the expected environmental consequences would negatively impact the population of Siberia. These discussions entered the public sphere and inflamed the situation: The last congress of the USSR Writers’ Union was even ironically nicknamed the “Congress of Land Reclamation” because this became its main topic of discussion.

Ultimately, on August 14, 1986, a resolution was issued by the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR “On the Cessation of Work on the Transfer of Part of the Flow of Northern and Siberian Rivers.” This decision put an irrevocable end to any hopes for partial water rehabilitation of the Aral Sea and doomed the entire vast water basin of Central Asia to environmental disaster.

This decision of the Center was received ambiguously in the then-Soviet Central Asian republics, and especially in their expert circles. Public concern began to be expressed in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the republics on whose territory the Aral Sea is located. The subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union greatly aggravated the situation. Central Asia was left alone to contend with the accelerating problems created by the drying-up of the Aral Sea and the degradation of natural landscapes.

From One Sea to Many Seas

At the end of March 1993, the five Central Asian republics—now independent countries—set up the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS). The heads of all five states expressed their shared responsibility for the preservation of the Aral Sea and its surrounding ecosystem. This project—which was hailed as one of the first signs of expected regional cooperation—made a lot of progress thanks to joint summits of the countries involved and funding from the World Bank. Unfortunately, however, there were insufficient political will and economic resources to fully address the disaster.

Ultimately, a dramatic loss of water in the Aral Sea led to the natural division of the sea into two reservoirs: the “Big” Aral (fed by the waters of the Amu Darya) and the “Small” Aral (fed by the waters of the Syr Darya) by the 1990s. The boundary of the watershed was the long island (then-peninsula) Kokaral. Already in the 1980s, these two Aral Seas were connected only by a 50-100-meter-wide channel on the site of the former Berg Strait. This canal was artificially maintained for cargo transportation from the city of Aralsk to the world’s largest military biological testing ground on Vozrozhdenie Island, located in the southern waters of the sea. The uneven rate of degradation of the northern and southern parts of the sea and the resulting difference in the level of the water surface caused sea water to flow predominantly from north to south.

The Southern (“Big”) Aral served as a giant evaporator of incoming water not only from the Amu Darya, but also from the Syr Darya. During the 1990s, through the efforts of regional authorities, attempts were made to build embankment dams in the former Berg Strait. Although they lasted less than ten years, these temporary dams significantly improved conditions in the Small Aral: in some places, the salinity of the water decreased to 15-20 ppm. Even the shallow water cover of the bare seabed led to a sharp decrease in salt storms, helping to stabilize the degradation of the Northern Sea. Meanwhile, the Great Aral continued to shrink and dry up, serving only as a giant evaporator, and only led to a worsening of the situation in the Small Sea.

The drop in sea level caused major damage to fishing: the only commercial fish at that time, flounder glossa, lost its commercial value.

Climate, Economy, and the Water-Energy Nexus

As a natural endorheic and vast lake in the center of the Turanian desert lowland, the Aral Sea served and continues to serve as the main climate-forming factor in the Central Asian region. The importance of this can be illustrated by the obvious relationship of the Aral Sea with the glaciers of the Pamirs and Tian Shan Mountains. Glacial waters, which flow into rivers, are the main source for replenishing the Aral Sea. In turn, the evolution of Central Asian glaciers depends on climatic conditions, which are created by precisely such a giant “humidifier” and regulator of air mass flows as the Aral Sea. In this functional multicomponent connection, which has developed historically, it is impossible to isolate a single “dominant” without destroying the entire fragile integral relationship and interdependence. Even more complex and functional multicomponent connections exist in hydrobiological, plant, and animal ecosystems throughout the Aral Basin.

Most researchers claim that the Aral Sea, which provides the entire region with moisture, influences the microclimate and the formation of dust storms; regulates the temperature of the atmosphere in Central Asia through the “sea effect and breeze;” and ensures the movement of atmospheric masses. Shrinking seas have also led to lower groundwater levels in agricultural areas, contributing to soil salinization, desertification, and general environmental degradation.

An important consequence of the Aral Sea crisis is the withdrawal of the Aral Sea from the economy of post-Soviet Eurasia. Prior to the crisis, more than half of the local labor force was directly engaged in fishing, and the sea was one of the main centers of the fishing industry throughout Central Asia. Today, this population is considered insignificant and its subsidized economy often falls out of consideration.

Meanwhile, water issues in Central Asia are often discussed without mention of the Aral Sea problem. It is a known fact that water resources in the region are distributed unevenly: Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are downstream countries and Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are upstream. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), per-capita water reserves in the countries of Central Asia are sufficient (about 2,300 m3). The problem, therefore, is not simply the scarcity of water resources, but their irrational use. FAO reports further state that Central Asian countries are among the top ten water consumers per capita in the world: Turkmenistan (5,319 m3/year), Kazakhstan (2,345 m3/year), Uzbekistan (2,295 m3/year), Kyrgyzstan (1,989 m3/year), and Tajikistan (1,895 m3/year). In addition, to obtain a unit of agricultural production, 2.5-3 times more water is consumed in the countries of Central Asia than in developed countries.

The main discussions on the topic of water balance in Central Asia are currently focused on hydropower issues in the upper reaches of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, as well as irrigated fields and irrigation water in their lower reaches. The possibilities of introducing a price for water, introducing drip irrigation, constructing water counter-regulators along riverbeds, fighting the reduction of mountain glaciers, and much more are discussed. Much less attention, at least in the media, is paid to the issue of preserving and replenishing the water balance of the Aral Sea itself.

Water as a Political Commodity

Over the past decade, the spirit of regional cooperation that had been forged in 1993 with the establishment of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea has somewhat faded. The water question has become a cause of numerous debates between the upstream and downstream countries and even recent violent clashes between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The issue has been further complicated by the inclusion of Afghanistan’s post-war reconstruction. At a 2012 conference in Tokyo dedicated to the post-war development of Afghanistan, there was voiced an idea of diverting part of the waters from the Amu Darya for the development of Afghanistan’s agricultural sector. According to press reports, in March 2022, the Afghan government began construction on the Kosh-Tepa canal (285 km long and 100 m wide) to provide water to the arid regions of the provinces of Balkh, Jawzjan, and Faryab, which will lead to the withdrawal of 15% of the water flow from the Amu Darya.

Meanwhile, in Turkmenistan the official press has repeatedly announced the start of efforts to create a “Turkmen Sea” using the water flow of the same river. Projects for the economic development of the “Arnasay Sea” at the expense of the Syr Darya are being developed in Uzbekistan. Tajikistan intends to build the Rogun hydroelectric power station on the Vakhsh River, a tributary of the Amu Darya. Kyrgyzstan is already building the Kambarata-1 hydroelectric power station on the Naryn River, the main tributary of the Syr Darya.

Also alarming are attempts to rename the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea as the Organization of the Aral Sea Basin Countries, which displaces sea issues as the primary focus. It is also worth noting that since it is the coastal residents of the Aral region of the Kyzylorda region of Kazakhstan and the Karakalpak Republic of Uzbekistan that have borne the main negative socio-economic consequences of the Aral catastrophe, these two countries are the ones making the greatest efforts to rehabilitate the Aral Sea, albeit with different results.

Kokaral Miracle

Today, the situation in the Aral region, and especially in the northern part of the sea (in the so-called Small or Kazakh Aral), as well as in the Syr Darya delta, has changed significantly. The construction of the modern Kokaral Dam finally divided the once-united sea into the Small Aral, at the mouth of the Syr Darya, and the dried-up Southern (Big) Aral, once fed by the Amu Darya. The water connection between them appears only periodically, during the discharge of water from the northern sea to the south, toward the salt desert, or Aralkum, formed on the now-bare Aral sea floor (Fig. 2).

The Kokaral dam came into operation in 2006 and marks a radical turning point in the Aral Sea crisis. All the water of the Syr Darya now replenishes the Small Aral, and excess water is discharged to the south, into the now-famous salty Aralkum desert. To date, various parts of the reservoir have been desalted to the previous 6-15 ppm, the surface of the sea has reached a size of 3,400 square kilometers, and its water volume has reached 27 cubic kilometers. In 2023, the water level in the Small Aral rose to 40.42 mBS (meters of the Baltic system). Spawning grounds for fish that have “rolled down” from the Syr Darya delta have reappeared. A significant adjustment is taking place in the ichthyofauna of the sea: instead of the only commercial fish in the 1990s, flounder (introduced in the 1970s from the Sea of Azov), the reservoir was repopulated with carp, pike perch, roach, bream, and other previously native fish species. Industrial fishing has developed rapidly, reaching 7,000 tons of catch per year and involving a significant part of the coastal population in the local economy. Both in terms of water volume and economic significance, the Small Aral is now the only heir to the once Great Aral. And the Small Aral is truly experiencing a time of revival.

Creation of the Quasi-Natural System

The stabilization of the Small Aral offers two extremely important conclusions for further consideration:

1) First, the natural conditions of the Aral region have essentially become a natural-anthropogenic and cultural landscape (in other words, a quasi-natural system.)

2) Second, fishing has revived and has become the main locomotive of local economic development.

However, it is worth emphasizing that all this apparent stability of the Small Aral is still based on man-made support. Anthropogenic impact can not only create new natural conditions, but also easily upset the balance in existing ecosystems with intensive resource exploitation. This is why, from a sustainability perspective, quasi-natural landscapes are considered imperfect, unnatural, and weak.

The success of the first stage of the project “Regulating the bed of the Syr Darya River and preserving the northern part of the Aral Sea” will apparently continue. In Kazakhstan, there are plans to build another dam in a northern direction, in the area of Saryshyganak Bay. Under this project, on the eastern shore of the Small Aral, it is planned to restore the Kamystybas and Akshatau lake systems in the Syr Darya delta, build an additional channel for transferring river water to the north of the Small Aral, and fill the Saryshyganak Bay. Such large-scale restructuring will lead to even greater transformation of the region. The waters of the Syr Darya will be more evenly distributed over the water area, and the currents, temperature, and saltwater regime of the entire reservoir will change.

Thanks to an almost twofold increase in the volume of water in the Small Aral, a sharp development of fishing and an increase in the volume of fish production to 30,000 tons can be expected. It is highly likely that in the near future, the Small Aral will turn into a two-level cascading reservoir with water covering a significant part of the dried bottom. This could have significant socio-political consequences: the city of Aralsk may once again turn into a coastal city, and the entire region may become a model for fighting environmental crises throughout Central Asia.

The Greater Aral and the Strategy for Its Restoration

The situation with the Greater Aral is in many ways more deplorable. It is no longer possible to preserve the great Aral Sea in its historical form. Currently, on the territory of the Greater Aral, there are two large, hypersaline reservoirs on the sites of the former Tuschybas and Chernysheva bays. At the mouth of the Amu Darya, which is completely waterless most of the year, there are a number of small reservoirs that are fed during water discharges outside the growing season. The Greater and Small Aral thus represent quite different bodies both in nature and in terms of prospects for further development and require an individual and specialized approach. Such a “reductionist (separate) approach” to saving the Aral Sea has already turned out to be justified in the case of the Small Sea.

But the Greater Aral Sea also has some interesting prospects for revival, at least for some of its natural landscape. A project is currently being discussed that would transform the chain of unstable Kendirli lakes and associated channels into the Barsakelmes natural biosphere reserve. If the hydraulic regime of this region were to be stabilized through the construction of small dams and canals, it would be possible to transform the currently uncontrolled wastelands into a protected wetland landscape under the Ramsar Convention, to which Kazakhstan is a party. A system of small reservoirs also exists on the territory of Karakalpakstan in the Republic of Uzbekistan.

The possible stabilization of the water situation in the Amu Darya delta, which is now widely discussed in all countries of Central Asia, implies not only the introduction of water-saving technologies on farmland, but also the creation of capacious water counter-regulators (water storage tanks for discharge outside the field-watering season). Moreover, some of these reservoirs have recently been included in the Ramsar Convention, and local ecologists are actively developing ties with international experts. Of particular interest are projects to introduce “water fees” throughout the Aral basin, which should have a significant impact on growing water consumption.

Of special note is the environmental strategy of “greening the former bottom of the Aral Sea,” which started several years ago in Uzbekistan and is now actively promoted in Kazakhstan. A number of experts believe that greening the new wastelands of the sea, especially in its southern part, by planting saxaul (Latin: Halóxylon), tamarix (Latin: Támarix), and other halophytes is one of the most effective methods for restoring the ecosystem of the Southern Aral Sea. Measures to “green the Aral Sea” are projected to lead to a reduction in the level of dust storms and air pollution, thereby improving the quality of life and health of the population. The project also entails restructuring degraded areas to preserve and increase biodiversity.

Both of the strategies discussed above—“irrigation of the Aral Sea” and “greening the Aral Seabed”—support the region’s progress toward becoming a quasi-natural landscape.

The author expresses the hope that this short review of the current situation in the Aral Sea can serve as a springboard for a discussion of ways out of the Aral crisis. Large-scale state projects and small-scale national ones can be combined under the initiative “The Salt of the Aral Sea Is Knocking on our Hearts.”

Literature:

- M. Tairov “The Aral Sea – is it possible to correct the largest environmental disaster in the world?” / Central Asian Analytical Network (CAAN), 08/01/2018, https://www.caanetwork.org/?s=%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2

- The Executive Board of the International Fund for saving the Aral Sea in the Republic of Kazakhstan, https://kazaral.org/

- Water management, irrigation and ecology of the countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, Information Bulletin of the ICWC of Central Asia, March 6-11, 2023, http://www.cawater-info.net/information-exchange/e-bulletin/6 -11-03-2023.pdf

- From Kattegat to the Aral Sea, https://www.facebook.com/pg/AralSeafishery

- V.Dukhovny, J. de Schutter «Voda v Tsentralnoi Asii. Proshloe, nastoyaschee I buduschee”, 2019. http://www.eecca-water.net/content/view/16335/12/lang,russian/