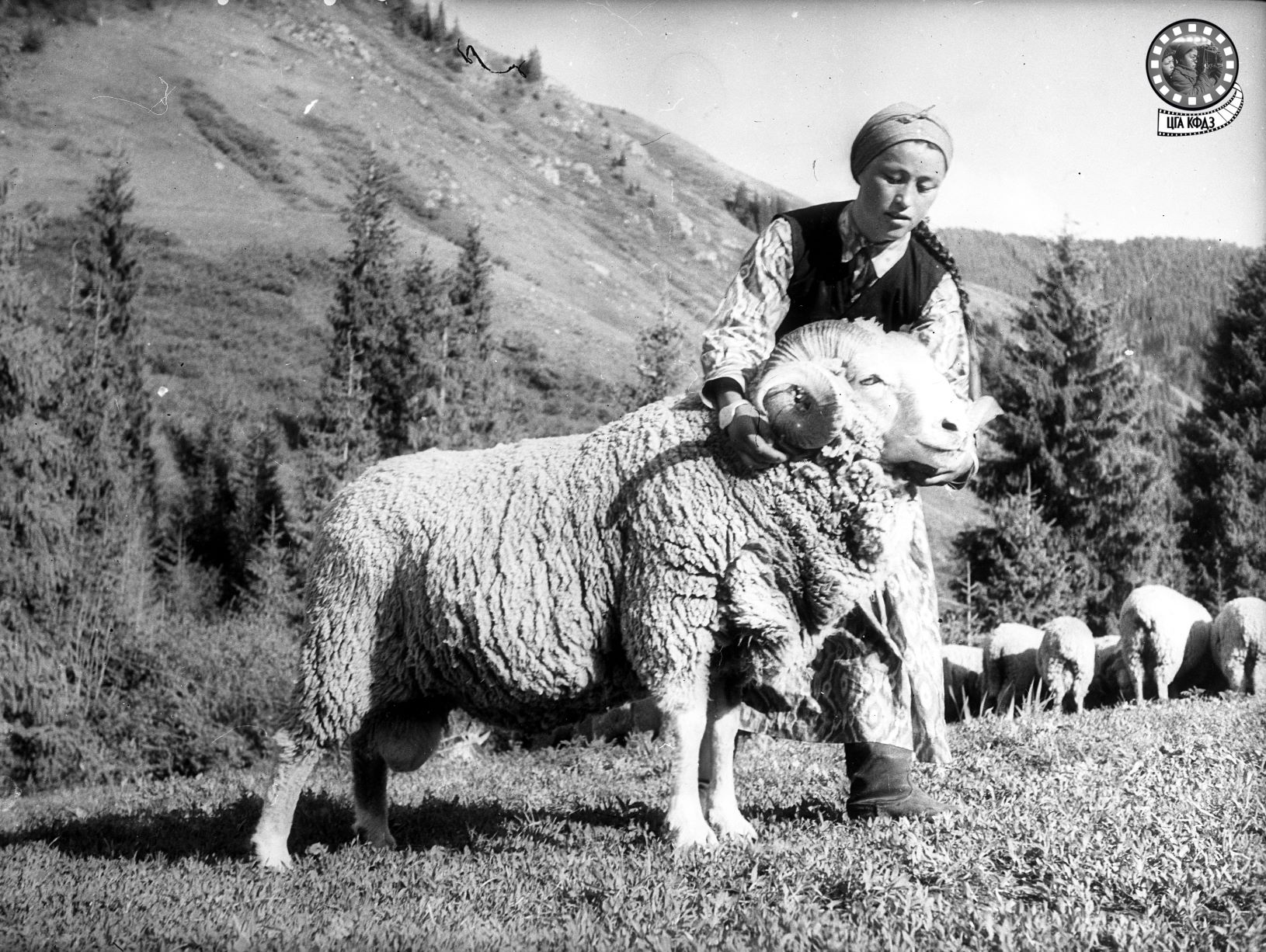

The lives of women in Central Asia before Russian colonization are often portrayed in a miserable light. European travelers did not leave much visual evidence about local women. Women in large cities (Bukhara, Samarkand, and others) did not dare to be photographed with bare faces and were often confined to female quarters. While there are some black and white photos of the Kazakh or Kyrgyz people of that era, which show women dressed in white dresses and elaborate headdresses, there is rarely a smile on their faces. Instead, they look strict and preoccupied. This is no wonder, as they are most often depicted actively engaged in manual labor, busily carrying huge bales and saddling horses.

Author

Askar Alimzhanov

Askar Alimzhanov graduated from the journalism department of the Kazakh State University named after S. Kirov. From 1986, he worked as a correspondent for the daily republican newspaper Leninskaya Smena. He also served as the editor-in-chief of the news service of the TV company “Tan.” In 1991, he worked as a reporter for the daily Cape Cod Times in Hyannis, Massachusetts. For a series of articles about Kazakhstan in the foreign press, he received an award from the Union of Journalists of Kazakhstan.

From 1997, he worked as editor-in-chief of the news service of the Khabar agency. Later, he held various positions in the administration of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Mazhilis of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Embassy of Kazakhstan in the Russian Federation, the TV and radio corporation “Kazakhstan,” the Interstate TV and radio company “MIR,” and private analytical centers. He is currently the director of the Central State Archive of Film, Photo Documents, and Sound Recording of the Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

This virtual gallery is made possible by the generous collection provided by the Central State Archive of Film, Photo Documents, and Sound Recording of the Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The lives of urban women and the inhabitants of the steppes and mountains were equally difficult. Yet the turn of the twentieth century brought many unexpected changes. In Kazakhstan, specialized women’s educational institutions emerged at the end of the nineteenth century. Thus began emancipation in the steppe. And already at the very beginning of the twentieth century, the first women’s rallies began to take place. In Semipalatinsk on March 18, 1907, the first women’s rally in Kazakhstan advocated for the charter of the emerging society of working women. The full equality of the rights of men and women was officially established by the Bolsheviks at the First All-Russian Congress of Women Workers, held on November 19, 1918. As they wrote then: “Soviet Kazakhstan joined the large-scale campaign to liberate the women of the East.” By 1924, universal suffrage had already been fully implemented in Kazakhstan. This is only four years later than women in the US got the right to vote—and much earlier than in Switzerland, where women won the right to vote in federal elections only in 1971.

The Bolsheviks envisaged mass labor involved in industry—and women were included in this vision. An increasing number of educational institutions began to appear, allowing women to master many professions that had previously been closed to them. Nevertheless, before the start of World War II, most women were employed in agriculture. This was due to the traditional way of life of the Kazakhs and undeveloped industry in Tzarist era.

Starting in 1941, when war broke out between Germany and the Soviet Union, industrial production in Kazakhstan picked up sharply, as the largest plants and factories were evacuated from the western part of the USSR to Central Asia. Workers were needed to man these new factories, and with most men going to the front, women had to take on these jobs.

The role of women during this period cannot be overestimated. Many Kazakh women fought and became heroes! Alia Moldagulova, Manshuk Mametova, Khiuaz Dospanov, and hundreds, maybe thousands, of women like them showed unparalleled courage in the face of a brutal war. Those women who lifted industry and agriculture on their shoulders in these most difficult years can likewise be called heroes. People were malnourished, but they sent everything to the front.

After the end of the Second World War, women’s lives did not improve. The happy photographs of that time—provided by the Central State Archive of Cinema, Photo Documents, and Sound Recordings of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Kazakhstan—are mostly staged. This is in line with the general tenor of the times. Only what was carefully censored was published. Photos of happy workers and their families occupied the central pages of newspapers and magazines. The mass media had to convince people that the country was on the path to prosperity and, of course, personal happiness! People needed to believe that the new world was in the making, all at the hands of the Communists, Komsomol members, and, as they wrote then, representatives of the intelligentsia.

In their parallel reality, women faced many problems. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, food supply was uneven. If in rural areas women could get by thanks to subsistence farming, the situation was more difficult for women living in cities, who faced queues for groceries, a shortage of high-quality consumer goods… The women of that era raised several children while working full-time in Soviet institutions and even advancing science! According to the 1989 census, the average Kazakh woman had five children. Thus, between 1959 and 1989, the population of Kazakhstan increased from 9.2 million people to 16.4 million. (As of 2021, Kazakhstan’s women had an average of three children, and in 2022, the population stands at 19.2 million.)

All these figures, of course, indicate that the well-being of the population has been slowly but steadily increasing—and the photos speak for themselves. As the lambs become larger, working women acquire new uniforms. Brand new tractors appear, as we see in the photo of Hero of Socialist Labor Kamshat Donenbayeva. And finally, in the 1970s, fashionistas arrive! How else can one understand the appearance of photographs of the beautiful Bibigul Tulegenova and Gulfairuz Ismailova looking at the Polish fashion magazine Uroda (“Beauty” in Polish)?

Of course, over the time that photography has existed, the lives and work of women in Central Asia have undergone dramatic changes. Today, the lives of women in Kazakhstan are not much different from those of women in any other country. They face all the same problems: love, family, health, children, work…

All photos by

the Central State Archive of Film, Photo Documents, and Sound Recording of the Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Republic of Kazakhstan.