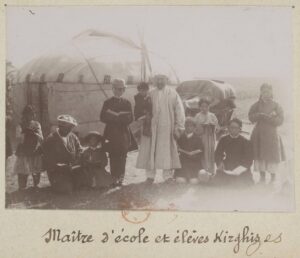

Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov

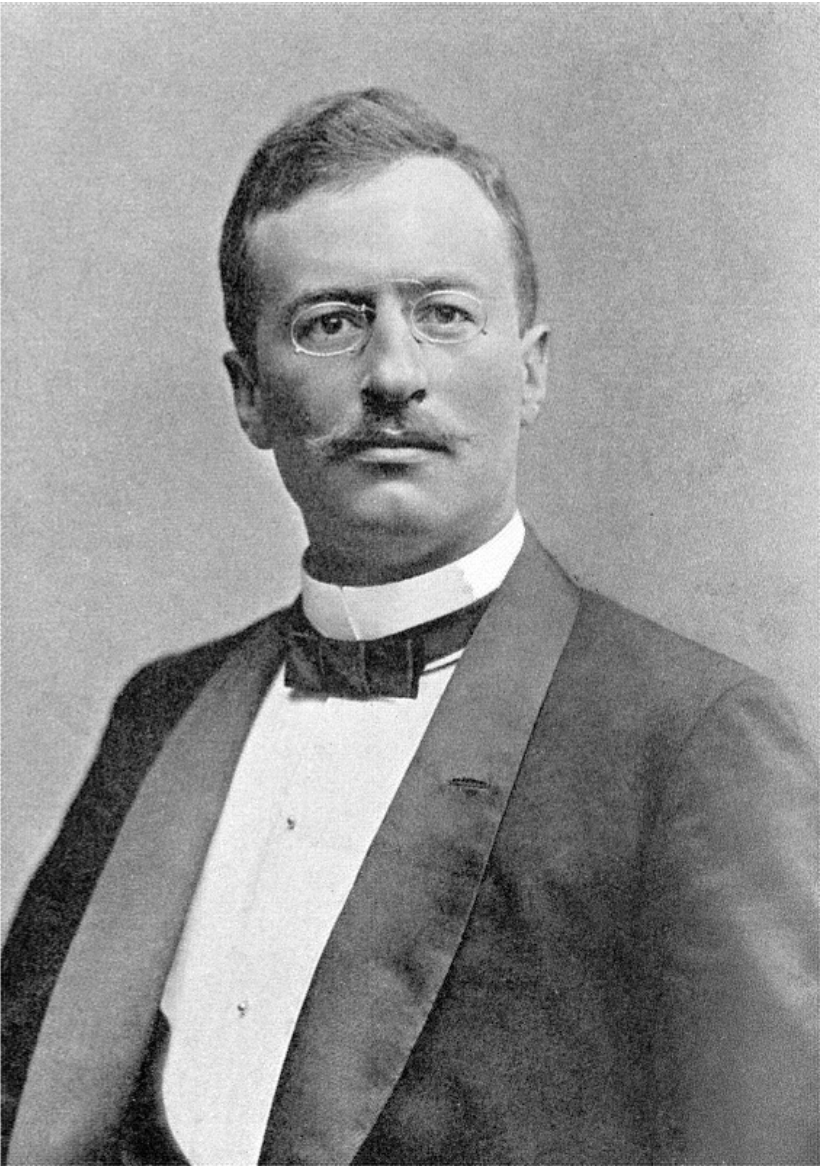

Sven Anders Hedin (19 February 1865 – 26 November 1952) was a Swedish geographer, topographer, explorer, photographer, travel writer and illustrator of his own works. Hedin’s expedition notes laid the foundations for a precise mapping of Central Asia. He was one of the first European scientific explorers to employ indigenous scientists and research assistants on his four expeditions to the region between 1893 and 1935.

Sven Hedin was born in Stockholm, the son of Ludwig Hedin, Chief Architect of Stockholm. When he was 15 years old Hedin witnessed the triumphal return of the Swedish Arctic explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld after his first navigation of the Northern Sea Route.

In his two volume work “Through Asia” of 1898, published in London and dedicated to His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales, Sven Hedin provides a resume of Central Asia exploration by saying that “a new era is approaching in the historical development of geographical discovery. The pioneers will soon have played their part; the “white patches” on the maps of the continents are gradually decreasing; our knowledge of physical conditions of the oceans is every year becoming more complete. The pioneers of the past, who declared the way through increasing danger and difficulty, have been followed by explorers of the present day, examining in detail the surface of the earth and its restless life, always finding new gaps to fill, new problems to solve. Although many regions have already been the object of detailed investigation, there are several still remaining in which the pioneer has not yet finished his work. This is particularly the case with the interior of Asia which has long been neglected… It was with the view of contributing my little to the knowledge of the geography of Central Asia that I set out my journey which this book describes”1.

Hedin’s work represents incredibly detailed accounts of his journey through Asia. We would like to draw the attention of our readers to his description of Kazakh steppes. He says that “between the river Ural, the Caspian Sea, Lake Aral, the Syr Darya, and the Irtysh stretches the vast level plain of the Kazakh steppe. Thinly inhabited by Kazakh nomads, the steppe is also the home of a few species of animals, such as wolves, foxes, antelopes, hares, etc., and there too certain prickly steppe plants struggle against the inclement conditions of the region. Where there is sufficient moisture, kamish or reeds grow in great quantities; and even the dried sandy wastes are diversified by the tufted bashes of saksaul (Anabasis Ammodendron), often attaining six or seven feet in height. The roots, which are excessively hard, provide the chief fuel to the Kazakhs, and are collected during the autumn for winter use. At nearly every aul, you see big stacks of them, and we frequently met large caravans conveying nothing else”2.

Overall, the author describes the climate as typically continental with cold winters and hot summers. He mentions that many Kazakhs own as many as 3000 head of sheep and 500 horses, and are considered to be in very good circumstances. Hedin also shares his observations of the Kazakh people and says that they are capable, healthy and good natured3.

According to Hedin, they love to call themselves kaisak, i.e. brave fighting men, are content with their lonely life on the steppes and worship freedom. In the struggle for existence, their lot is a hard one. Their herds are their chief means of subsistence, providing them with food and clothing, The scanty vegetation and the soil itself furnish materials for their dwellings. The long, growing roots of the saksaul protect them against the cold of winter.

What is incredible is how Hedin catches the very essence of Kazakh feelings towards the vast steppe they lived in. He says that “they cherish a devoted love for their desolate steppe, where their forefathers lived the life of freedom, and find it beautiful and varied, although the stranger seeks in vain for an object on which to rest his eye. It is true that like the sea, the steppe is grand and impressive”4.

“they cherish a devoted love for their desolate steppe, where their forefathers lived the life of freedom, and find it beautiful and varied, although the stranger seeks in vain for an object on which to rest his eye. It is true that like the sea, the steppe is grand and impressive”.

photo credit: steppestravel.com

Today, travelers across the globe are keen to visit Kazakhstan during the spring time to take advantage of the good weather and experience the country’s natural beauty firsthand. Interestingly, in his 1898 account, Hedin also says that during the spring season, the air is perfumed with delicious scent of flowers, for vegetation develops with incredible rapidity.

We also loved Hedin’s descriptions of Kazakh character, a distinct feature that is very well-known and admired by many. As Hedin puts in, “as might be supposed from the physical conditions of the region in which they live, the sense of locality and power of vision displayed by the Kazakhs are developed to a high degree of keenness and exactitude. In a country across which the stranger may travel for days and days, without, so far as he can perceive, anything to vary its indication of a road, the Kazakh finds his way, even at night, with unerring certainty. Nor do heavenly bodies serve him as a guide. He recognizes every plant, every stone; he notices the places where the tufts of grass grow more thinly or closely together as usual. He observes irregularities in the surface which a European could not discover without an instrument. He can discriminate the color of the horse on the horizon before the stranger, with the best will in the world, is even able to discover its presence”5.

Even more heartwarming are Hedin’s portrayals of his life among Kazakhs on page 284. In this chapter, Hedin elaborates saying that he gradually learned to have much sympathy with the Kazakhs. He lived amongst them for four months a solitary European, and yet never once, during all that time, felt lonely. The friendship and hospitality they showed him never wavered. They shared with willing pleasure in the hardships of his nomad existence; and some of them were at his side in every sort of weather, took part in all his excursions, all his mountain ascents, and all his expeditions across and to the glaciers. Hedin then shares how he earned some level of popularity as people came from far and near to visit him at his camping stations; bringing him presents of sheep, wild duck, partridges, bread, yak’s milk and cream. And almost invariably, Hedin notes, when he drew near to an aul, he was met by a troop of horsemen and escorted to the beg’s yurt, given the place of honor near the fire and offered dastarkhan.

What we find fascinating is Hedin’s feelings about this experience that he describes as following. Hedin says that Kazakhs too understood that he regarded them as friends, and felt at home amongst them. Hedin shares, “I lived constantly in their yurts, ate the same food they did, rode their yaks, wandered from district to district as they did, – in a word, became to all intents and purposes a full blooded Kazakh. They often used to say to me : ““Siz endi Kazakh bo oldiniz” (You have become Kazakh now) 6.

Hedin’s portrayals of how his Kazakh friends hosted him during his travels go beyond depictions of everyday life and also share his experience of baiga, which the author describes as mounted games exceeding anything that household can produce in terms of romantic and fascinating effects. At one of such events, Hedin describes his brief meeting with a local Kazakh man, “with oblique, narrow eyes, prominent cheek bones, thin black beard and coarse moustaches who rode a coal black horse and had a vibe that one could define as a True Asiatic Don Quixote” 7.

Beyond doubt, one could spend hours unfolding one Hedin’s story after another as his works indeed represent a wonderful portrayal of Kazakh nomadic life in 1890s. This is an absolutely stunning account of personal observations and it is amazing how he connected with Kazakhs on such a deep and spiritual level. We definitely recommend our readers to explore Hedin’s writings on Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Perhaps, like ourselves, you will find your very own stories that impress you most.