Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov.

As we continue exploring the writings of Western travelers who visited Kazakh soil, we would like to draw your attention to the book entitled “Through Russian Central Asia” written by British journalist, travel-writer and novelist Stephen Graham (1884-1975) prior to the World War I.

As Graham puts it, “the journey recorded in these pages was made in the summer before the great war…the record of my impressions and the story of my adventures were fully written in my road diary and in the articles I sent to “The Times” (p.9) that we believe makes this book to stand out even more as it engages readers in daily observations of life in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. The author describes his time there as “the gentle and innocent present that was more interesting than past or future” (p.102).

The book is full of fascinating facts and findings as well as author’s personal experiences which make this reading even more engaging and adventurous. This time we would like to invite you to join our journey of discovering how the cities of Kazakhstan looked like back more than 100 years ago and what similarities and differences we notice today.

It is not a secret that Shymkent, now Kazakhstan’s third largest city, has been a long favorite of western travelers for many decades thanks to its unique entrepreneurship and cultural spirit.

It is even more interesting to read how Graham depicts his time in this city back in 1914, recalling it as a beautiful town that has mountain background, its white stemmed, magnificent polars and fortifications (p.96). We believe the readers would enjoy learning more about Shymkent bazaars at that time. The author describes them very accurately as following:

“The Sartysh bazaar was full of life and colour, carpenters, smiths and metal workers doing their work in open booths, koumis merchants standing behind gallon bottles and little glasses, inviting you to sit down there and then and drink a glass, the white of the milk gleaming suggestively through the gloomy green of the bottle, silk and cotton vendors exposing marvelously gaudy wares to veiled who tried to look at the stuff without exposing their faces, a difficult maneuver; strawberry hawkers, hawkers of lepeshka, carpet vendors, saddle vendors” (p.96).

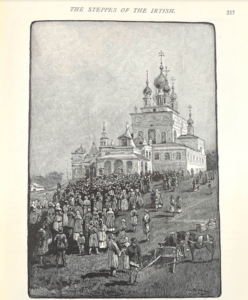

Graham also travelled to another Kazakh ancient city, then named Aulie-Ata, and nowadays – Taraz. The author describes how he went to find a room to stay the name of which he found fascinating, – Hotel London, thousand miles away from his homeland (p. 114). He then explains in the vast detail the cultural background of the city. In particular, he notes that “the foundation of the settlement is Mohammedan. It was once a great holy place of the Moslems, the shrine of some antique teacher…”. What is even more interesting, he then adds that there are hotels, cinema shows, restaurants, theaters as well as farmhouses, shops, sarais, mud dwellings and fixed Kazakh tents. It is fascinating how Graham could grasp the eclectic nature of Kazakh towns back then influenced greatly by historical and geographical processes as well as international trade and progress.

Graham’s conversations and interactions with locals led not only to an interesting portrayal of their daily lives, but also the information on the population density. According to some of the figures put in by him, located 64 and 242 versts from the railway station, Shymkent and Aulie Ata had a population of 15 756 inhabitants, – 19 052 respectively.

Graham also provided very generous and accurate records of Seven Rivers province, whereby he notes that it is “well-known for its natural wealth and the beauty of nature” (p. 162). He notes that the principal inhabitants of this province are wandering Kazakhs, of whom there are about one million.

He then continues by describing the capital of the Seven Rivers Land, Verney. The author adds that Verney has its own bazaar, its inns, dance halls, clubs and restaurants. He then continues with comparing Verney to his native London and “says the city has its own Covent Garden. Verney is a great market for fruit and vegetables. Its native name means the city of apples, and for apples it is famous”. An interesting fact shared by the author is that all travelers from China are given apples when they pass through.

Indeed, even today, then Verney and now Almaty, the southern capital of modern day Kazakhstan is still well-known for its markets with fresh and organic products as well as world famous for its wonderful aport apples.

What we find as a very interesting comparison is that “in Verney there is a suggestion of America in the life here. When you ask the way you are directed by blocks, not by turnings, and you may be sure the town is a planned one, with the streets running the right angles to one another. There is much advertisement of wares and of persons, and a keenness to prosper and get rich” (p.173).

In this sense, he continues by saying that Verney has its rich bourgeois – men with ten or twenty thousand pounds capital. Among such, he adds, was a German sausage maker who started his career at the market place with five pounds of sausages on a plate and is now a respected merchant with shops and branch shops throughout Central Asia.

This unique feature demonstrates that Kazakhstan has been always a getaway to prosperity and economic growth, even back in the days. Today this spirit of nomadic capitalism is even more vivid seeing how our country built an open market economy with thriving trade and investment partnership with all the countries of the world.

We hope that our readers will enjoy this book as much as we did and find a story in Graham’s travelogues that personally touches them most.