Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov.

Eugene Schuyler (1840–1890), little known today, was one of America’s most prominent diplomats of his time, one of the first to hold a PhD degree, a friend of Tolstoy, translator of Turgenev, and biographer of Peter the Great. Schuyler spent a decade in Russia; his first book describes a nine-month trip through Central Asia.

In Central Asia, Schuyler was able to combine his diplomatic duties with both scholarship and travel. He began writing a major biography of Peter the Great, and frequently attended meetings of the Russian Geographic Society in St. Petersburg. In 1873, he was one of the first foreigners invited to visit Central Asia and brought back a wealth of geographical information and insight.

The records indicate that Schuyler left St. Petersburg by train on March 23, 1873 and traveled first to Saratov. He was accompanied by an American journalist, Januarius MacGahan, who was working for the New York Herald. Schuyler and MacGahan traveled from Saratov by sledge to Orenburg, then to Kazala (now Kazalinsk, Kazakhstan), then to Fort Perovskii (now Kzyl-Orda, Kazakhstan).

Schuyler wrote extensively about his trip for the National Geographic Society in the United States, and he also wrote a long report for the State Department. The two volume book we would like to review is entitled ‘‘Turkestan’’, was published in October 1876, in both the United States and United Kingdom.

Schuyler begins his fascinating journey with almost only fellow passenger in a carriage, Prince Tchinghis, a lineal descendant of the famous Tchinghis khan, and son of the last Khan of the Bukeief Horde of Kirghiz. Eugene describes him as “a good Mussulman who had just returned from Mecca, where he had been on a pilgrimage, and was going to spend the summer on his estates in the Government of Samara”. The author also adds that he seemed a cultivated gentleman, and was most of the time deep in a French novel.

Following the detailed and in-depth accounts of his travels in the region, Schuyler describes his encounters with Kazakhs and the etymological meaning of this word. Thus, he writes, “the name Kazak, as used in Central Asia, means simply a vagabond or a wanderer, and its application is evident” (p.30).

What we find very unique for that time is Schuyler’s description of the Aral Sea. He famously wrote that the “water looked so clear and pure that he scooped up cup of it and drank it. In taste it was slightly brackish but not strongly saline” (p. 27). Eugene then continues with providing the analysis of water by providing Mr. Teich’s 1871 accounts of its composition.

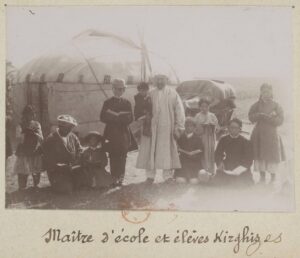

Through the observations during his travel, Schuyler brilliantly describes Kazakh families who were going from their winter to their summer quarters seeking pasturage from their cattle and flocks in the steppe. These descriptions through the eyes of Western traveler provide a valuable insight into the nomadic way of life in the territory of Kazakhstan. In particular, we would recommend to get acquainted with his portrayals of long caravans of horses and camels laden with piles of felt, tent-frames, and household utensils. Eugene explains that Kazakhs are in general breeders of cattle and sheep, and their search for fresh pastures is the main cause of their migrations over the Steppe (p.36).

Interestingly, this book also provides a number of historic accounts, including the story of Kazakh Sultans Girei and Jani Bek and how they have created a flourishing community. Eugene also shares the accounts of how Kazakhs were divided into three parts, the provinces of Turkistan forming the Middle Horde, the Great Horde going to the east, and the Lesser Horde going to the west and north.

Whilst sharing the historic accounts, Schuyler also describes Abul-Khair, the Khan of the Lesser Horde, as a remarkable man – enthusiastic and able (p31).

In addition to the historic accounts, Eugene Schuyler was the first American diplomat to provide national characteristics and common traits of Kazakhs. He wrote that Kazakhs stood up for their tribes and families in defence of the honor and safety of their members. Reverencing at the same time bravery, dash, and boldness, and loving their freedom, they were always ready to follow the standard of any batyr or hero such as Syrym, Arunhazi or Kenisar, who might appear in the Steppe. He then adds that one of the best traits is their respect for age and the authority of their superiors. Eugene adds that they are found to make excellent scouts, partly from their untirigness, and partly from their acquaintance with nature and capacity for observation. Eugene then continues by adding that they can see or somehow divine a way in the darkest night, and it seems hardly possible for them to get lost in the desert or steppe. They measure space by the distance which the voice will reach or the eye can observe. They are not cruel by nature. An interesting observation as even centuries later Kazakh diplomacy centers on its interests as a peace-loving nation.

What is truly fascinating about Schuyler’s contribution to the study of Kazakhs at that time is not only that Eugene describes their character and way of life as a nation, but also provides detailed accounts of the demographic situation and major sources of income. According to Schuyler, “it is very difficult to calculate the number of Kazakhs but so near as can be ascertained by the return of taxes, there are about a million and half”. In the Great Horde, the district of Alatau, there are about 100 thousand of both genders, in the Middle Horde there are 406 thousand and in the Lesser Horde there are 800 thousand. Schuyler also accurately describes the flocks and herds as the source of wealth for Kazakh families. Here Schuyler notes that it is not easy to calculate the amount.

Perhaps another important contribution in Schuyler’s records is how he portrays the traditional wear of Kazakhs at that time. Eugene wrote that men wear baggy leather breeches and a coarse shirt with the wide flapping collars. Their outer garment is a dressing gown, and they usually wear two or three, according to their weather. The rich and distinguished have magnificent velvet robes with gold and silver. A red velvet robe is given by the Government as a mark of distinction. But their greatest adornments are their belts, saddles, and bridles, which are often so covered with silver, gold, and precious stones as to be almost solid. The women are dressed the same as men, but have their heads and necks swathed in loose folds of white cotton cloth, so as to make a sort of bib and turban at the same time. They spin, embroider and very well too, cook and do most of work.

It is a well-known fact that modern-day Kazakhstan is one of the top producers of wheat in the world and contributes greatly to the global food security. Interestingly, Schuyler writes that there has been found such a lucrative occupation to raise wheat the Kazakh Sultans, and after them, the lower classes of the community, have with eagerness engaged in agriculture.

Eugene pays a special attention to describing Kazakh cuisine. In particular, he is fascinated by kumys – a liquor made of fermented mare’s milk. He says that kumys is sourish to the taste, but not unpleasant, and possesses agreeable exhilarating although not intoxicating qualities. He then adds that it is rapidly coming into the use in Russia, as a cure for many diseases.

Having been invited to a Kazakh toi himself, Eugene Schuyler writes about Kazakh feasts with a degree of admiration and awe. He says that a circumcision, a marriage or a funeral feast among Kazakhs is a signal for a large festival accompanied by games and horse-races. He adds that besides racing there is usually wrestling, and especially the national sport of baiga, where one man holds a goatling thrown over his saddle, and everyone else tries to tear it from him.

For those interested in studying the correlations between geography and trade, Eugene provides incredible accounts of his travels across Kazala and Syr Darya. He mentions that Kazala lies in junction of all trade routes in Central Asia. Here, too, is the chief post in the river of Syr Darya. Should the Asiatic trade be developed, Kazala is likely to become a considerable commercial centre, and even now the trade is large. While at Kazala, Eugene also had an opportunity to visit and inspect the steamers and barges of the Aral flotilla which were then moored there, but before speaking of it, Schuyler also provides incredibly detailed accounts of Syr Darya river.

He says that Syr Darya or River Syr (darya means river or water course), was known to the Greeks as Iaxartes, and was said by Strabo and others to empty into the Caspian Sea. He then continues that the Arab geographers of the Middle Ages called it the Sihun, and no European traveller in Central Asia mentions the river before the Englishman Anthony Jenkinson, and in his map, made in 1558, he marks it as falling into the Aral Sea. But even in spite of this on the maps of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it is marked as flowing into the Caspian.

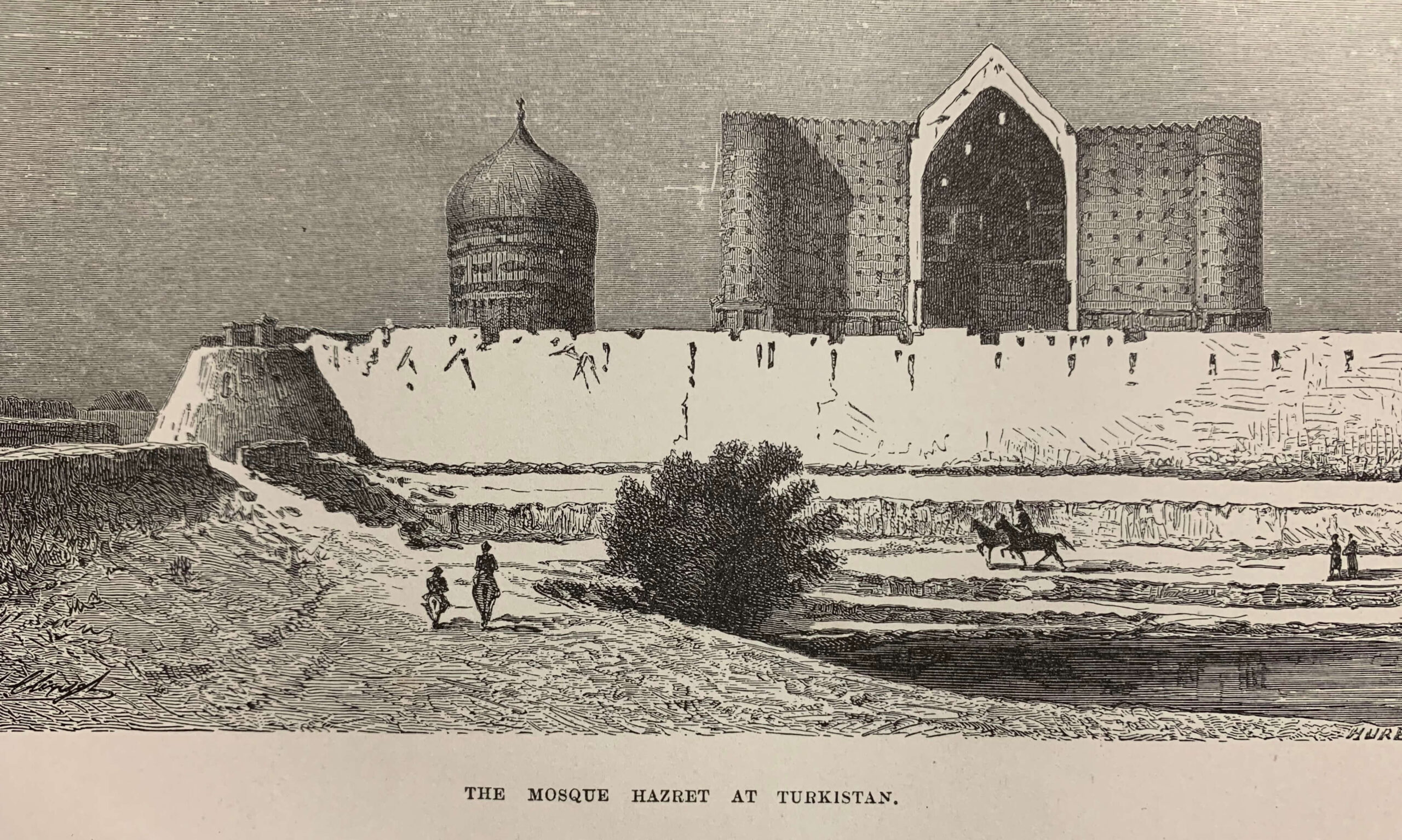

What is even more fascinating is Schuyler’s depictions of Turkistan. He famously wrote that when he approached Turkistan, Eugene saw groves of dark green trees, looking darker and richer by contrast with the Steppe around them. As he passed between the narrow lanes between high clay walls, Eugene wrote, he saw branches of apricot trees, and occasionally the faces of little boys and girls looking with curiosity at equipage, till, making a circuit of the town and fort, above which rose the immense vault of a splendid mosque. That was the famous mosque over the tomb of Hazret Hodja Akhmed Yasavi. The construction of this mosque he continues his writings, begun by Timur in 1397, who went on a pilgrimage to Turkistan, or Yassy, as it was then called, while waiting for his new bride, Tukel-Khanym.

Schuyler describes the mausoleum is an immense building, crowned by a huge dome, and having annexed to the rear another small mosque, with a melon shaped dome. The front consists of an immense arched portal, at least a hundred feet high, flanked by two round windowless towers. In the archway he writes there is a large double door of finely carved wood, and over this is a small oriel window, dating from the last reconstruction by Abdullah Khan. The walls are of large square-pressed bricks, well burnt, and carefully lad together.

In the middle of the mosque is the enormous hall, under the lofty dome which rises to a height of over a hundred feet, and is richly ornamented with alabaster work in the style common in Moorish buildings, especially seen in Alhambra. American diplomat gives further detailed accounts by describing the layout of the mosque. On the right and left are rooms filled with tombs of various Sultans of the Middle and Lesser Hordes, among them the celebrated Ablai Khan. One room answers for a mosque, where the Friday prayers alone are said, while under the small dome at the back of the building are the tombs of Akhmed Yasavi and his family; and opening out of a corridor full of tombs is large room of a sacred well.

Eugene concludes his portrayals by saying that this mosque is considered the holiest in all Central Asia and had very great religious importance.

To conclude, it is worth noting that this two volume book is full of fascinating facts and findings representing very rare and valuable accounts of their time. Beyond doubt, it is impossible to give a complete overview of this significant work and I believe every reader will find their own enchanting pages of Kazakhstan history, culture and tradition by reading this book and embarking on a journey to Turkistan in the 19th century.